If you really love your peaches and want to shake a tree, there's a map to help you find one. That goes for veggies, nuts, berries and hundreds of other edible plant species, too.

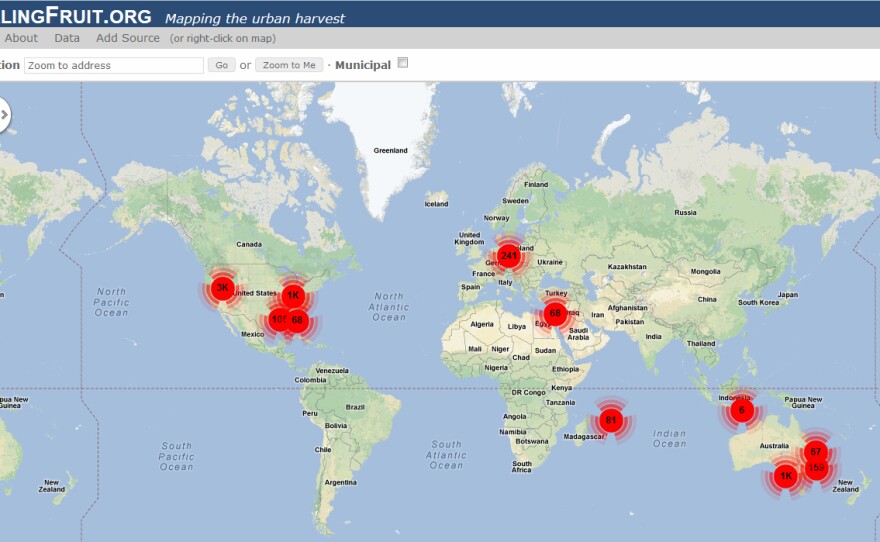

Avid foragers Caleb Philips and Ethan Welty launched an interactive map last month that identifies more than a half-million locations across the globe where fruits and veggies are free for the taking. The project, dubbed "Falling Fruit," pinpoints all sorts of tasty trees in public parks, lining city streets and even hanging over fences from the U.K. to New Zealand.

The map looks like a typical Google map. Foraging locations are pinned with dots. Zoom in and click on one, and up pops a box with a description of what tree or bush you can find there. The description often includes information on the best season to pluck the produce, the quality and yield of the plant, a link to the species profile on the U.S. Department of Agriculture's website, and any additional advice on accessing the spot.

Welty, a photographer and geographer based in Boulder, Colo., compiled most of the locations from various municipal databases, local foraging organizations and urban gardening groups. Additionally, the map is open for public editing - Wikipedia-style.

"I'm a data geek," Welty says. "I feel like there is power in getting everything onto one map. A map is like a very narrow lens on the world, but I think it's very powerful because of how narrow it is."

Clearly, with dozens of countries boasting thousands of foraging destinations, it's practically impossible for Welty and Philips to verify all of the spots. Welty says they have to rely on the honesty of the contributors when it comes to listing trees in potentially off-limit locations, like private properties or fenced-in parks. In many of those cases, the entry contributors tell potential foragers to ask the property owners for permission. The map has more than 6,700 crowdsourced entries so far.

The duo says they created Falling Fruit essentially to form a community for novice and pro foragers alike. Philips, who is a computer scientist based in the San Francisco Bay Area, says there's value in pulling a carrot from the ground or an apple from a tree to eat.

"If I can apply my skills to help people realize that there is a fruit tree down the street that they can pick, then that's just a simple thing I can do to reconnect people with how food works and get them away from the notion that food is only in a grocery store," he says.

Now, the map doesn't limit its entries to fruits and veggies. Welty says it also lists beehives, public water wells, and even dumpsters with excess food waste.

"There is someone who posted a squirrel with a recipe for him," he says. "Gray squirrel is an invasive species. He's encouraging people to hunt for squirrels, so hey, why not?"

Welty says he hopes the map and its stable of contributors will keep growing - so much so that it ends up influencing cities' land use and management plans.

"The big goal, in a way," he says, "is to make people realize that there is potential [for foraging in cities] and deliberately create food forests, like the Beacon Food Forest and others around the country -- to rethink what a city should look like."

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.