Women and girls are less likely to undergo female genital mutilation, or FGM, than 30 years ago. That's the encouraging news from a UNICEF report on the controversial practice, presented this week at London's first Girl Summit.

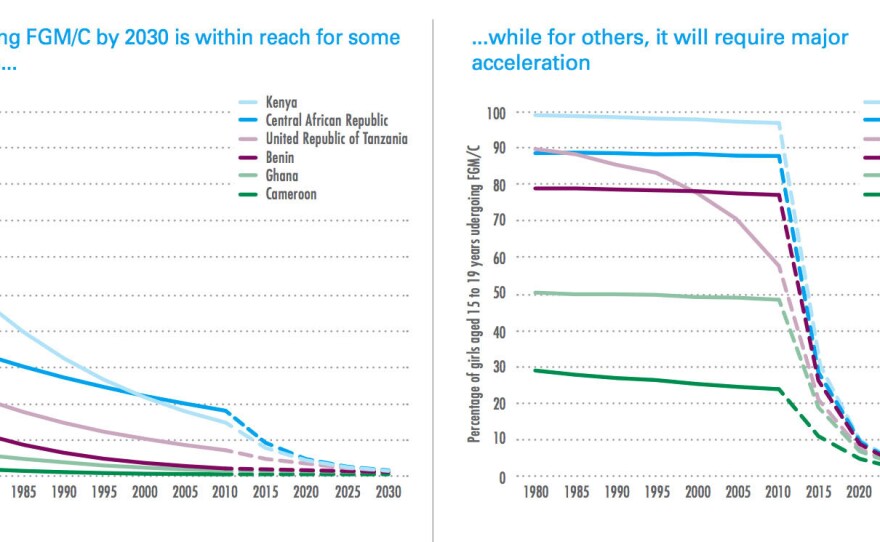

The rate has dropped in many of the 29 countries across Africa and the Middle East where FGM is practiced. In Kenya, for example, nearly half the girls age 15 to 19 were circumcised in 1980; in 2010 the rate was just under 20 percent.

But there's a sobering side to the report. In countries like Somalia the rate has gone down slightly but is still over 90 percent.

And because the population is growing in parts of the world where the practice takes place, total numbers are on the rise. Unless the rate of decline picks up, another 63 million girls and women could be cut by 2050.

The report is "exciting and worrying," says Susan Bissell, the chief of child protection at UNICEF. "The population growth will far surpass the gain we've been seeing if we don't step it up."

The report shows that more than 130 million girls and women have experienced some form of genital cutting or mutilation in 29 countries across Africa and the Middle East.

The practice involves removing, partially or completely, the female genitalia – sometimes just the clitoris, other times also the labia or "lips" that surround the vagina. In extreme cases, the vaginal opening is narrowed by sewing up the outer labia.

In many communities, the custom has long been perceived as a rite of passage into womanhood. Because sexual contact is painful, the practice is also seen as a way to prevent a woman from losing her virginity before marriage. Some see it as ensuring fidelity during marriage, as the procedure eliminates sexual pleasure.

The practice persists partly because it's a social norm in male-dominated societies. Mothers have said they only have their daughter's best interest in mind. "The decision to cut is partly based on your interest in your daughter being able to marry within your community," Bissell says. "If she is the only who isn't cut, her marriageability prospects go down dramatically."

In some countries, like Egypt and Indonesia, FGM gets added legitimacy because doctors perform the surgery. There's the idea that "Oh, if a doctor does it, it's ok," says Shelby Quast, the senior policy director of Equality Now, an international human rights organization.

"There are laws in the book that say that if you do this through a medical doctor, it's not a crime."

But "it's a human rights violation regardless of who does it," she states.

In countries where FGM is prevalent, simply condemning the practice isn't enough. Education needs to be strengthened and attitudes toward women and girls need to be changed, says Bissell.

Quast points to Kenya as a success story, citing their laws against female genital mutilation and prosecutors who actively go after people who cut girls. Kenya has also tackled an underlying economic issue that other countries ignore: being a circumciser is somebody's livelihood.

"The government is helping find other ways for those people to make a living," she says.

It helps that more people are becoming involved in the fight to end FGM.

Despite the staggering numbers from report, Bissell is excited to see progress in the number of women taking a stand. Young girls who are at risk are less afraid to speak up. And women have drawn attention to the problem by sharing their own experiences and protecting their daughters.

Public figures like Sister Fa, a hip-hop star from Senegal who was cut, have spoken out as well. "She's a rapper so she's got this young following," Bissell says.

Bissell calls her a brave "change-maker" who campaigns despite disapproval from those in her community, who accuse her of casting a bad light on Senegalese culture.

"Ten years ago, it was like a handful of feminist organizations talking," Bissell says. "But now everybody's talking and when you have public discourse, things change."

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/