A new technique that could fight diseases like malaria and Zika by rewriting the rules of genetic inheritance isn't ready for use in the wild, according to a report released Wednesday.

The report was written by a panel of experts convened by the National Academy of Sciences. It offers ethical guidelines on "gene drives," which could in theory alter an entire species — or drive it to extinction — in a short period of time.

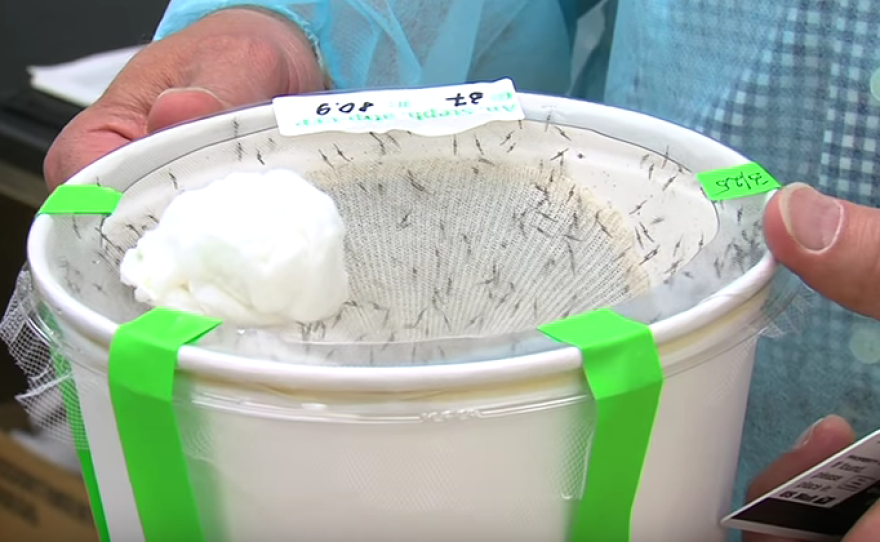

Recent experiments involving researchers at UC San Diego have shown that gene drives could prevent mosquitoes from spreading malaria, which kills more than half a million people each year.

But gene drives could also alter animals and their environments in unexpected ways. The report concludes the technique should not yet be used in the real world. Instead, it recommends moving forward with highly contained research to refine the technology and establish its safety.

"This advance, which has the prospect of bringing a lot of benefits associated with it, must be approached cautiously," said James Collins, a professor at Arizona State University and co-chair of the panel.

Work on gene drives has been accelerated in recent years by CRISPR, a gene editing tool that gives scientists the power to make targeted changes to an organism’s DNA. Gene drives would then ensure those changes are passed down to subsequent generations, rapidly changing populations through a sort of genetic chain reaction.

National Academy of Sciences' report cites UC San Diego molecular biologists Ethan Bier and Valentino Gantz as the first scientists to show gene drives can work in insects. In a 2015 study, Bier and Gantz used a gene drive to create fruit flies that pass down a recessive trait to their offspring with nearly 100 percent certainty.

Their study was the subject of some controversy. Other scientists argued the UCSD team could have taken stronger precautions to prevent the genetically modified bugs from escaping the lab and changing wild fruit flies, perhaps permanently.

The UCSD researchers later co-authored an article in Science calling for gene drive researchers to "always use safeguards adequate for preventing the unintentional release of synthetic gene drive systems into natural populations."

In a subsequent study, Bier and Gantz worked with UC Irvine scientists to show that a gene drive could spread anti-malaria genes through mosquitoes.

The expert panel's report raised the possibility of researchers creating a gene drive to prevent mosquitoes from spreading the Zika virus. Such discoveries could ramp up pressure to release modified bugs in the wild in the name of public health, the report says.

"How much risk are we willing to take to possibly get that benefit?" asked Michael Kalichman, director of UC San Diego's research ethics program. "That's something that individuals, societies and the world community will be asking in the coming months."

But none of today's gene drives are ready for use in the real world, according to the report, which calls for more lab work and highly controlled field experiments to study the unintended effects that might arise from releasing such animals into complex ecosystems.

The report also points out confusion over who should regulate gene drives. In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Agriculture or the Environmental Protection Agency could all have a claim to oversight.

Animals outfitted with gene drives, by their very nature, would not stay confined within national borders. The approach to gene drives could vary from country to country, and it’s unclear which international body would oversee their release.

"There is a strong cultural component to the application of gene drive technology," Collins said.

The report recommends any plan to use gene drives in the wild should include input from members of the public and communities who would be affected.

"To move forward without the understanding and consent of the community that’s being affected, " Kalichman said, "we risk having that community being more skeptical of science and more distrusting. And in the long run that lack of trust in science could be harmful for all of us.”