The nonprofit behind a six-figure contribution to a group opposing Measure B, which would allow the proposed Lilac Hills Ranch development in Valley Center to move forward, will not have to disclose its donors before Tuesday’s election.

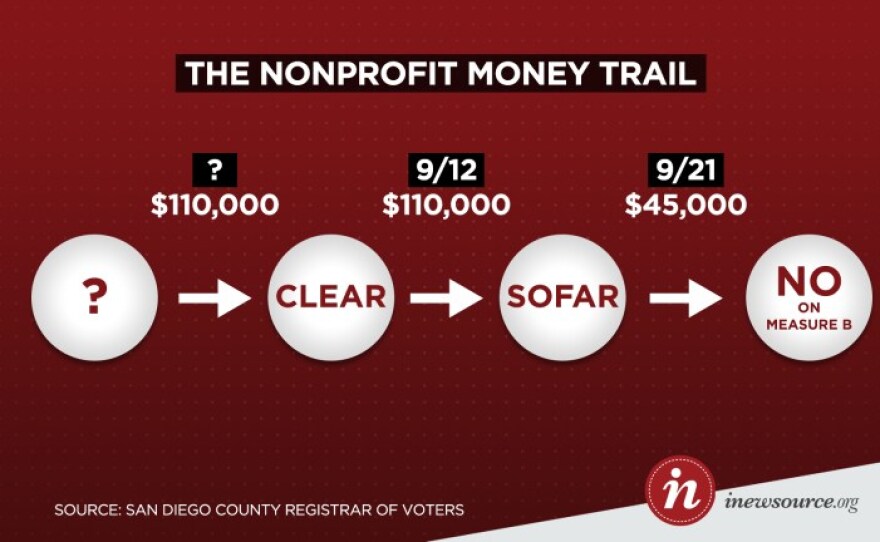

Superior Court Judge Jay Bloom refused a request Friday for a temporary restraining order that would have forced California Local Energy — Advancing Renewables (CLEAR) to disclose the source of a $110,000 donation it made to Save our Forest and Ranchlands. That nonprofit, also known as SOFAR, went on to give $55,800 in two donations to Citizens and Taxpayers Opposed to Lilac Hills Ranch, the political committee established to run the campaign against Measure B.

An inewsource story two weeks ago raised questions about the money flow from CLEAR to SOFAR and eventually into Citizens and Taxpayers Opposed to Lilac Hills Ranch.

“I don’t think courts — if they don’t need to — should get involved in the democratic process,” Bloom said before delivering his decision that rested, in part, on the notion that voters’ knowledge of CLEAR’s funding wouldn’t change the outcome of the election.

The ruling and the lawsuit that prompted it stand as the latest chapters in the bare knuckles brawl over Measure B, which asks county voters to authorize the 1,700-home planned community in a rural area north of Escondido.

Supporters of Accretive Investment’s project say it fulfills a need for affordable housing and tout it as “smart growth.” The project’s detractors say it’s too intense for the area, violates the county’s general plan and will increase greenhouse gas emissions.

County voters will write its final chapter Tuesday at the polls.

Bill Powers, CLEAR’s treasurer, was pleased with the result. He said the lawsuit, which was filed by Lilac Hills Ranch supporter Nancy Layne, was a “tempest in a teapot.”

“To have a complaint filed with the FPPC, to have a lawsuit filed against us — we have to be ready to deal with any of this,” Powers said. “We’re taking on a very deep-pocketed developer with a very direct financial benefit if this measure passes. So, it’s good. It’s good that we won.”

Jeff Powers (no relation), a spokesman for Accretive, said the company disagreed with the ruling.

“The Yes on B campaign’s followed the law. We’ve disclosed our campaign funds every single step of the way,” Powers said. “And the No on B campaign has not.”

He said he didn’t know whether Accretive would finance further legal action against CLEAR.

The $50,000 question

The suit centered on state regulations adopted in 2014 that require politically active nonprofits spending more than $50,000 in campaigns to disclose their donors.

Accretive paid for the lawsuit, filed Wednesday, but Layne was the actual plaintiff. She is a Valley Center resident, real estate agent and vocal supporter of Lilac Hills Ranch who often speaks to the media on behalf of Accretive.

Jim Sutton, the attorney representing Layne, pointed to the 2014 regulations to argue the case was simple.

“Save Our Forest said, “We received $110,000 from CLEAR. Period,’” he said in court. Later he added, “The law is incredibly clear: Over $50,000, you disclose your donors.”

Cory Briggs, CLEAR’s attorney, didn’t disagree with Sutton’s interpretation of the law but questioned whether it covered CLEAR’s contribution to SOFAR.

Briggs told the court Sutton couldn’t prove that the entire $110,000 CLEAR donated to SOFAR was intended for political purposes since none of either group’s officers had testified.

He noted that SOFAR does advocacy work unrelated to politics and that the group could have “over disclosed” or overstated the amount of money it spent opposing Measure B, thus pushing it above the $50,000 threshold for triggering a nonprofit’s donor disclosure requirements.

Briggs also said that no one had established if SOFAR had existing funds it could have used for the expenditures against Measure B. (At the end of last year, SOFAR had only $165 in assets. It hasn’t reported revenues over $500 since 2008.)

At several points in the course of his arguments, Briggs returned to the fact that CLEAR had only been served papers on Thursday and so was unable to collect evidence that could rebut the arguments Sutton was making or correct any erroneous campaign finance reports.

“You’re being asked to make a whole bunch of assumptions on 24 hours’ notice,” Briggs told Bloom.

Sutton argued that CLEAR had enough time to correct any errors in paperwork and to confirm the intent of the donation to SOFAR.

“If there was a mistake, they’ve had six weeks to correct that mistake,” Sutton said, referring to the date SOFAR filed a report disclosing the CLEAR contribution.

“Certainly they’ve had the three weeks since the FPPC complaint was filed,” Sutton continued, referring to a complaint Layne filed with the state Fair Political Practices Commission on Oct. 19 about CLEAR’s refusal to disclose its donors.

In the end, Bloom agreed with Briggs.

While saying that he took “the issue of dark money very seriously,” he had to rely on evidence presented in the case.

Bloom agreed CLEAR, SOFAR and Citizens and Taxpayers Against Lilac Hills Ranch were not given sufficient notice to fully respond to the complaint. He also said it wasn’t clear that Layne would win on the case’s merits, saying the campaign finance reports disagreed with each other.

Finally, he said Sutton had failed to show “irreparable harm” to the integrity of the electoral process — a crucial bar that must be met when a judge considers requests for emergency restraining orders — since he doubted that voters would be swayed by knowing the identity of CLEAR’s donor or donors.

Despite the court ruling, CLEAR may still have to reveal its donors as the investigation by the state’s Fair Political Practices Commission — triggered by Layne’s Oct. 19 complaint — into the group’s political activities continues.

FPPC fines SOFAR

While Friday’s court hearing was a victory for Lilac Hills Ranch’s opponents, that same day, the Fair Political Practices Commission announced a blow to one of the lawsuit’s defendants.

The commission announced that it would consider at its Nov. 17 meeting a proposed settlement between Save Our Forest And Ranchlands and the FPPC’s enforcement division.

In the proposed settlement, SOFAR admits to failing to file four campaign finance reports: a statement of organization when it qualified as a political committee; a report within 24 hours of receiving the $110,000 contribution from CLEAR; a report within 24 hours of making the $45,000 contribution to Citizens and Taxpayers Opposed to Lilac Hills Ranch and a regularly scheduled pre-election report on Sept. 29 disclosing all contributions and expenditures.

The FPPC could fine SOFAR as much as $15,000. However, the commission’s enforcement division recommended the commission level only a $5,000 fine because SOFAR promptly filed the reports after being contacted by the FPPC and the group had no prior campaign finance violations.

Duncan McFetridge, the nonprofit’s president, said his group tried to follow the campaign finance laws but just didn’t understand all the regulations (this was the first time his group was involved in electoral politics).

“We were late. We were innocently late,” McFetridge said. “Were we trying to do the right thing? Of course we were.”