Man's interference with Colorado River floods that used to regularly flow to the Salton Sea may have "stopped the clock'' on a regular series of big earthquakes, setting the stage for a megaquake that could wreck Southern California, scientists said today.

A massive 7.5 or larger quake may be the result when the southern San Andreas Fault finally jolts back to life, causing waves of enormous destruction in the Inland Empire and Los Angeles basin, a Scripps Institution of Oceanography study published today said.

The findings were published in the scientific journal "Nature Geoscience,'' and were first reported by the San Diego Union-Tribune's signonsandiego.com web site.

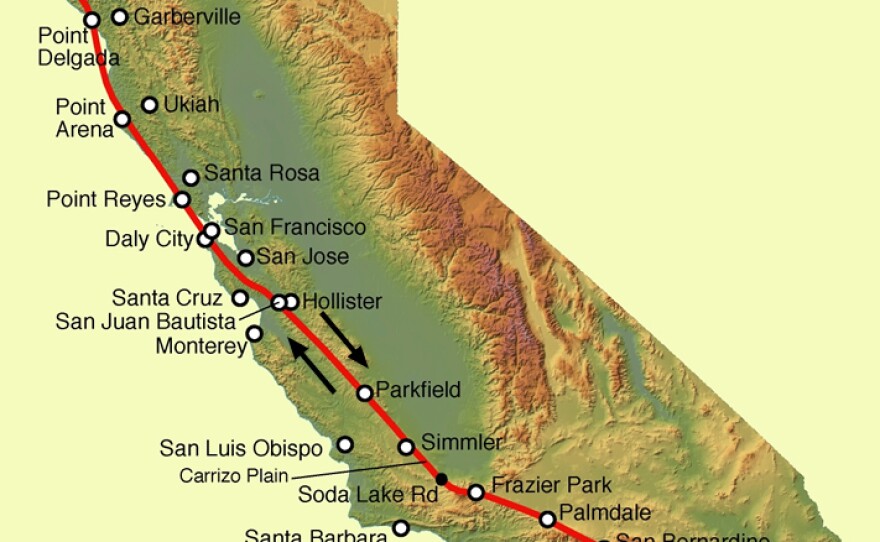

The seismically-active southern end of the San Andreas Fault Zone lies under the Salton Sea, a wide depression whose bottom is about 250 feet below sea level. The area was regularly flooded by the Colorado River over the

Between that diversion, the construction of upstream dams near Las Vegas and regional droughts, the Colorado has not flooded into the Imperial Valley and Salton Sink, a dry lake bed that was converted to the Salton Sea in gigantic floods in 1906. The Colorado last flooded and reached the Sea of Cortez in 1982, but it now trickles into the sand about where the San Andreas fault crosses the International Boundary 155 miles east of San Diego.

The new Scripps study shows that several heretofore unknown fingers of the San Andreas system sit beneath the Salton Sea, and the sand and dirt of the Imperial Valley. The faults let loose with magnitude 7.0 quakes or larger every 180 years until the early 20th century -- the same time that the Colorado floods that had brought billions of pounds of water to the area were staunched.

"It's possible that the ending of the diversion re-set the earthquake clock; we're more than 100 years overdue for a quake that could be as big as 7.5,'' said Neal Driscoll, quoted by signonsandiego.com .

"The fault could send tremendous energy towards the Los Angeles area if it broke from south to north, and could cause shaking that would make soil liquefy in bays and estuaries in San Diego County,'' Driscoll told the U-T's web site.

The Scripps study suggests that the Colorado River flooding may have affected the timing of the smaller, stress-relieving faults.

The study covers the area just north of the zone struck by the 7.2 magnitude Mexicali Easter Sunday quake of 2010. It killed two people in Mexico, and although it was felt as a nasty sway in the Inland Empire and Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego counties, damage was limited to Imperial County and the Baja California state capital, Mexicali.

Because the magnitude scale is logarithmic, a 7.5 quake is 1,000 times stronger than a 7.2 quake.

The new Scripps study includes maps that show the San Jacinto and southern San Andreas fault lines bracketing the Imperial and Coachella valleys, and a curlicue-shaped Imperial Fault beneath El Centro and Mexicali, home to more than 1 million people.