Sir David Attenborough was eight years old in 1934 when he saw his first natural history film. It featured the popular naturalist Cherry Kearton, one of the earliest pioneers of wildlife photography and filmmaking. “Kearton’s films captured my childish imagination,” says Attenborough. “It made me dream of traveling to far off places to film wild animals.”

“I’ve been lucky enough to live through what well might be considered the golden age of natural history filmmaking.” – Sir David Attenborough

Years later, those dreams became an illustrious reality. For over half a century, Attenborough has been at the forefront of natural history filmmaking, witnessing an unparalleled period of change in our planet’s history. His first-hand accounts offer a unique perspective on the natural world.

As he marks his 60th anniversary on television, NATURE presents "Attenborough’s Life Stories," a three-part retrospective of his life and work on PBS. The mini-series focuses on three areas that he believes have been transformed most profoundly during his time: filmmaking, science, and the environment.

"Life On Camera" (Episode One) repeats Wednesday, July 17 at 11 p.m. - Attenborough revisits key places and events in his career and shows how a succession of technical innovations in filmmaking led to remarkable revelations about our planet and the creatures that inhabit it. The introduction of video cameras in underwater photography was a huge breakthrough in extending the time cameramen have to capture the most dramatic shots of animal behavior, such as swimming with dolphins and marlin hunting, without artificial lights.

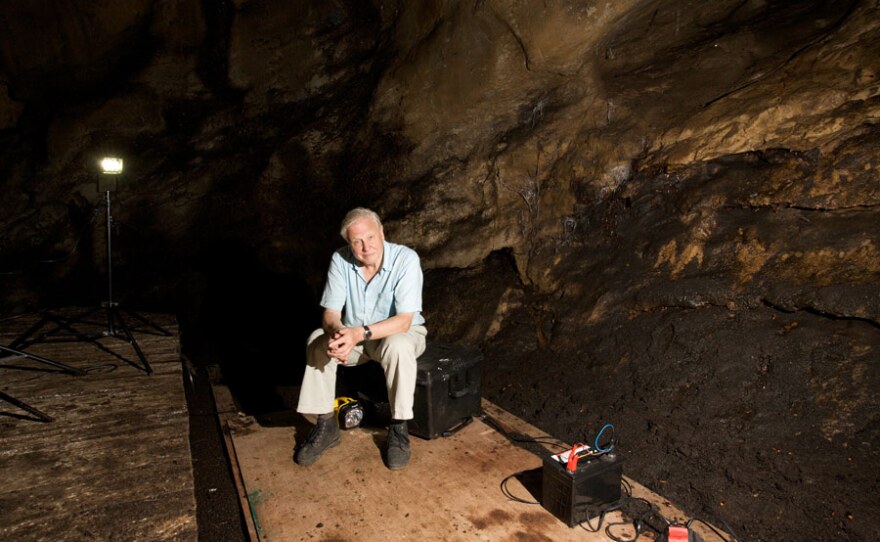

Returning to his old haunts in Borneo, Attenborough recalls the challenges of filming on a seething pile of guano in a bat cave, especially when the lights went out, and how to catch a komodo dragon. He also shows how the invention of infrared film cameras made it possible to film one of the most amazing nocturnal hunting sequences ever recorded and proved that a pride of lions can kill an animal as big as an elephant.

Other innovations include the stabilizing camera mount, remote controlled camera, time lapse photography, and digital slow motion cameras. The latter, recording what is impossible to see with the naked eye, caught one of Attenborough’s favorite moments: tricking a lovesick hoverfly into thinking that the objects Attenborough was shooting out of a peashooter were females whizzing by.

"Understanding The Natural World" (Episode Two) repeats Wednesday, July 24 at 11 p.m. - Attenborough shares his memories of the scientists and the breakthroughs that helped shape his own career in translating these discoveries into film. Attenborough is seen interviewing Austrian scientist Konrad Lorenz who studied animal behavior and geese in particular.

Lorenz determined that if he was the first thing young goslings saw when they hatched, they would follow him as they would a parent. This process, known as imprinting, was a boon to filmmakers who could film animals behaving naturally in the wild.

Demonstrating some of the thrilling attempts to bring new science to a television audience, Attenborough is seen standing in the shadow of an erupting volcano as lumps of hot lava crashes around him. He’s describing how continental drift, caused by volcanic eruptions on the sea bottom, explains why a closely related group of animals can occur on both sides of an ocean.

Following up on his boyhood fascination with a book illustration showing a bird of paradise being hunted by native tribes, Attenborough ventures to New Guinea in search of the elusive bird and is charged by a group of armed tribesmen until he offers a handshake signaling his peaceful intent.

Eventually his cameraman filmed a plumed male and unplumed female, possibly the first film ever taken of a bird of paradise displaying in the wild, but Attenborough returned 40 years later with better cameras and the ability to shoot high up in the trees. Among other topics featured are DNA fingerprinting, chimpanzee behavior and Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

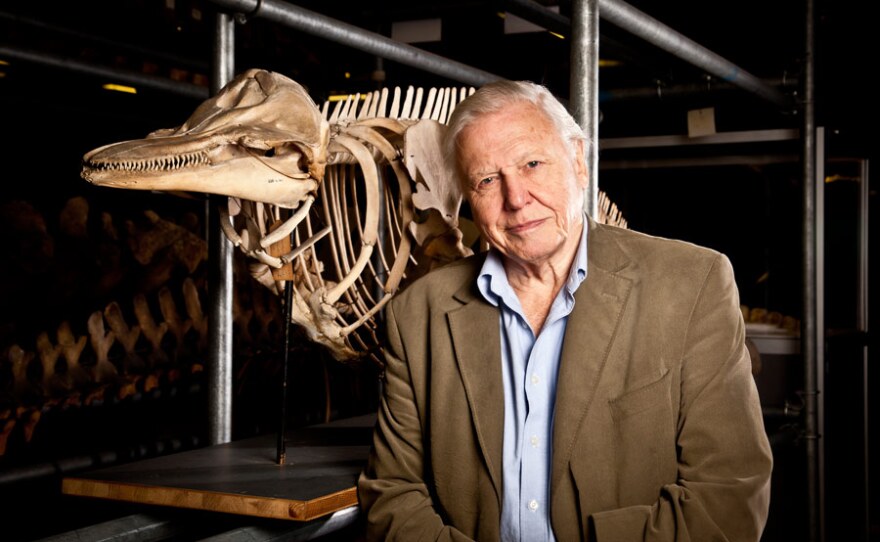

"Our Fragile Planet" (Episode Three) airs Wednesday, July 31 at 11 p.m. - Attenborough reflects on the dramatic impact that we have had on the natural world during his lifetime, such as the disappearing rain forests and coral reefs, endangered species such as the blue whale, manatees, sea otters, chimpanzees, and orangutans. He notes how the vulnerable Panamanian golden frog is now quarantined for safety so it doesn’t succumb to a highly infectious fungus which has already made the Monteverde Toad from Costa Rica extinct.

He tells surprising, entertaining and deeply personal stories of the changes he has seen, from his early travels with the London Zoo collecting animals; showing viewers the world’s rarest living animal, the giant Galapagos tortoise, Lonesome George; to covering the work of Dian Fossey, whose life’s mission to study and protect the endangered mountain gorillas in Rwanda inspired him to become a conservationist.

But Attenborough also reviews the revolution in attitudes towards nature that has taken place around the globe. He cites the creation in 1961 of the World Wildlife Fund, the first international organization to spend money on conservation projects around the globe, and protections put into place in Borneo and Malaysia to protect birds and turtles.

He concludes with a warning about the consequences of sea ice melt: exposing the dark sea water that doesn’t reflect the sun’s heat to keep earth cool. Unlike ice and snow, it absorbs the sun’s heat, raising the sea temperature and its level. Climate change, he says, is already affecting the lives of not only wild animals, but ourselves.

After the broadcast, each episode will stream at pbs.org/nature. NATURE is on Facebook, and you can follow @PBSNature on Twitter.