What’s in a Referendum?

San Diego City Attorney Jan Goldsmith is happy to wax poetic—and historic—on the nature of referendums.

He harkens back to a time when California’s government was controlled by the big barons of the Union Pacific Railroad, and the little guy had little say in the role of government.

“Around the turn of the century, there was a movement that was called the progressive movement—a little different than it was today,” Goldsmith said. “But it was a progressive movement that had at its core direct democracy.”

Along with that movement came radical ideas: the initiative, the recall and the referendum. These are some of the most essential and most solid rights of direct democracy, according to Goldsmith.

These tools are “stronger than any other rights in our process,” Goldsmith said. “If you don’t like something the city council did, you have got a period of time where you can get together a bunch of signatures and you can overrule them.”

Referendums provided a moment in which the politically powerless could take control.

Mesa College political scientist Carl Luna said that is the genesis of the referendum.

“When referendums were introduced in California in the early 20th century, they were part of the progressive movement—giving the average citizen the chance to be heard in Sacramento and in local city government,” he said.

But Luna said it was only a matter of time until that paradigm was turned on its head.

“I have an expression: when you try to limit the power of powerful people, they will use their power to get around the limits," he said.

Citizens in San Diego have seen a rise of referendums in recent years and months. But not everyone agrees this points to a surge of direct democracy. Some see instead what Luna alludes to, the powerful using the systems in place to get around the limits.

The Price of a Referendum

The tricky fact these days is that waging a referendum—an attempt to undo a law passed by the San Diego City Council—costs money. For one, it costs money to pay signature gatherers to station themselves outside of supermarkets across the city.

Outside of my local post office in Ocean Beach, a signature gatherer called out to passers by, “Come on man, I get paid $5 if you sign, just a signature…”

But what exactly are people signing for?

That is where it gets a little bit murky.

Take the recent Barrio Logan Community Plan Update passed by the City Council. The shipbuilding industry opposed the plan and helped finance a referendum campaign.

In front of an Albertsons supermarket in Allied Gardens, paid signature gatherers told voters that the City Council had voted “to build condos” and “shut down the shipyards.”

But the story told by the signature gatherers was not entirely true—the new plan actually forbids the building of residential housing in a proposed buffer zone along the port.

Another example of fuzziness in referendum advertising happened around the City Council-passed plan to charge fees on new developments to help finance low-income housing.

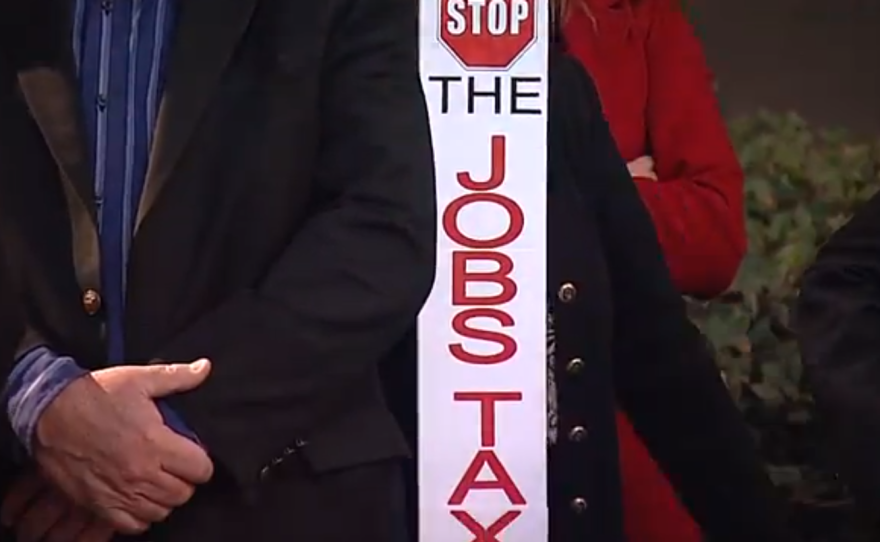

At a Vons supermarket in Carmel Valley, signature gatherers set up tables emblazoned with a large sign reading: “Stop the Jobs Tax: Keep San Diego Business Friendly.”

Former San Diego Mayor Jerry Sanders was holding court alongside the tables, and many who remember his key role in turning the city around showed up to sign, no questions asked.

“This is a new tax?” one man asked, “then sign me up right now against it!”

The only problem is it is not actually a tax, according to City Attorney Goldsmith. “They are running around calling it the job tax. Well if it was a tax, it would be illegal; we’ve given an opinion: it’s not a tax, it is a fee.”

The so-called "linkage fee" is what developers would pay on new construction that would go to building more affordable housing.

But in front of the supermarket the nuances of policy are lost. The signature gatherers call it a tax, and that rankles Goldsmith.

Goldsmith says when he hears the claim, he winces a bit, “Every time I hear that it’s like, 'Ah, but that’s their right, that’s their opinion.'”

An opinion, Goldsmith says, that has absolute legal status in a referendum campaign.

I asked Goldsmith at what point the signature gatherer was crossing the law by stretching the truth. He told me that unless there was outright fraud in the petition actually signed, paid signature gatherers can say what they want.

Goldsmith pointed out that hyperbole is part of process. He said if “the signature gatherer told me this will change the course of history in San Diego and everyone will lose jobs,” that would be OK. “A judge is going to think in the back of his or her mind about the Supreme Courts direction, this is one of the most precious rights and defend it if we can and let them give their puffery.”

According to Goldsmith puffery is part of the process, it might obscure the issue, but it protects the process of direct democracy.

Still, this picture of moneyed interests paying signature gatherers to sell half-truths is a long way from where the concept of referendums began.

Does The Referendum Process Favor Those With Deep Pockets?

Is the referendum process—so long a participant in reform—broken or misused?

San Diego’s interim Mayor Todd Gloria said he thinks referendums have become the tool of the wealthy. He believes that money has watered down the process, “where once the less powerful used it to call the powerful to account.” Now, “it really has been turned on its head, with special interests using direct democracy to get outcomes they cant get through the normal democratic process," he said.

Gloria said to find the answer, look no further than the issues that have been challenged lately.

“When you look at the issues that have received challenges because of the referendum process,” he said, “I think it's fair to say that each of those issues are relatively progressive issues, that have been challenged by fairly large, fairly well moneyed interest.”

San Diego Housing Federation’s Susan Riggs has been fighting for years to get developer fees passed by the Council to address the crisis of affordable housing in San Diego, and she sees this latest referendum campaign as more of the same.

“We have a very long tradition in San Diego of deeply embedded real estate interests, military interests, corporate interests that have generally been able to throw money at a problem and get what they are asking for,” Riggs said. “That is really the history of this city—the referendum process is just another example of throwing money at a problem to try and get what the opposition would like to see in an outcome.”

But former San Diego Mayor and Chamber of Commerce CEO Sanders said referendums create checks and balances on an overreaching government. He has been fighting to overturn the developers fees and he says the rise in referendums results from a lack of compromise at City Hall.

“I think what it is a response to is a majority on the city council that will not discuss those decisions and negotiate them,” Sanders said.

“When the business community or any other community thinks they have no avenue to have those conversations – then I think you see things like referendums pop up,” Sanders said.

Does The Referendum Process Need Reform?

The growth of partisan politics can also be seen as the growing pains of a city that is shifting from red to blue. According to Gloria, the policies passed by the new City Council are not trying to ravage the rights of business.

“No one can ever come into my council chamber and say that my colleagues and I do not stand for helping to grow business,” Gloria said.

But Gloria said the City Council’s attempt to create a new feeling of parity has created dissent, “we have to do that with some balance—and I think it’s the balance—that equilibrium that’s being shifted to more equity that I think people are pushing back against.”

In the case of these new referendums, they are pushing back hard. Are moneyed interests controlling who gets to push a referendum? Perhaps, said Goldsmith. But he added that money is in every part of politics and that shouldn’t shut out the direct democracy enshrined in the referendum process.

“I’m a little concerned about removing the ability to put something on a ballot, if somebody wants to spend something, the Supreme Court has said that’s speech—that’s no different than if you want to publish your article,” he said.

And in the end the referendum process can only buy so much. Goldsmith said the strongest claim of the referendum is that ultimately it returns policy questions to voters.

“We all have our vote, if we are better voters, if we dig deep to get information, if we ask questions, if we do our due diligence, all of that won’t matter,” Goldsmith said.

The voters will decide the Barrio Logan Community Plan Update in June. It seems they will also decide whether or not the linkage fee is just a developer fee or a tax on businesses—if not in June, then on the November ballot.

What is clear is that while the right to referendum is open to any one, the price of paying for one is open mostly to those who can foot the bill.

That leaves voters asking just who can afford the price tag of taking on City Hall, and if the newly Democratic San Diego City Council has caused moneyed interests to try and fight back through another kind of ballot box—not on the front end of elected officials, but through the back end of referendums.