MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: The man that Easterners still insist on calling Governor Moonbeam has had some unexpected setbacks recently. Governor Jerry Brown tried to convince a handful of Republicans on a measure that might have averted drastic cuts to the state budget. He was unsuccessful.

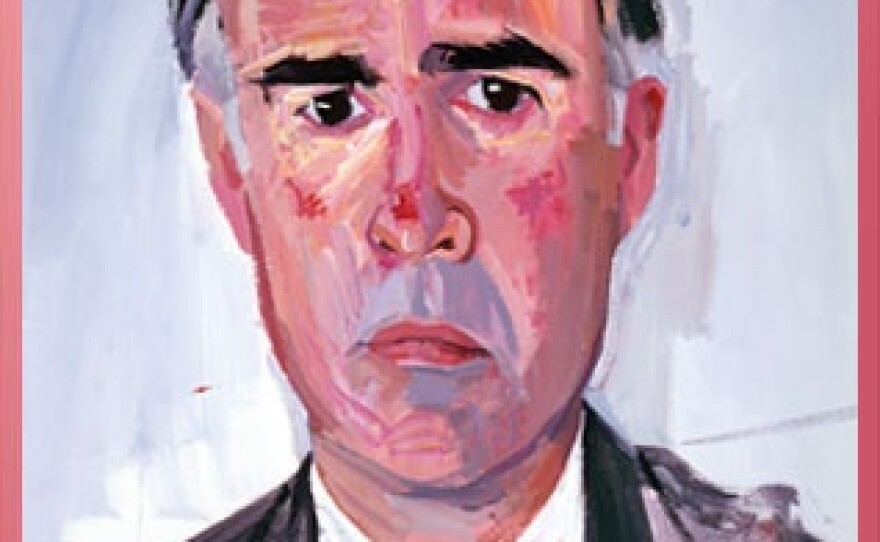

Now, as a profile piece in the New York Times Magazine suggests, Governor Brown may be ready to call that bluff and prescribe some very harsh medicine to our state.

GUEST: Adam Nagourney, Los Angeles Bureau Chief, New York Times.

Read Transcript

This is a rush transcript created by a contractor for KPBS to improve accessibility for the deaf and hard-of-hearing. Please refer to the media file as the formal record of this interview. Opinions expressed by guests during interviews reflect the guest’s individual views and do not necessarily represent those of KPBS staff, members or its sponsors.

CAVANAUGH: I'm Maureen Cavanaugh and you're listening to These Days on KPBS. The man that easterners still insist on calling good afternoon moon beam has had some unexpected setbacks recently. Governor Jerry Brown tried to convince a handful of Republicans on a measure that might have averted drastic kits to the state budget. He was unsuccessful. Now as a profile piece in the New York Times magazine suggests, Governor Brown may be ready to call that bluff and prescribe some very harsh medicine to our state. I'd like to welcome my guest, the writer of the New York Times magazine profile called Jerry Brown's last stand. Adam Nagourney, Los Angeles bureau chief for the New York Times. And Adam, good morning.

NAGOURNEY: Hey, how you doing?

CAVANAUGH: I'm doing great. Thank you for joining us.

NAGOURNEY: Thanks for having me.

CAVANAUGH: Well, what kind of access did you have to Governor Brown for this piece? It reads like you spent a lot of time with him.

NAGOURNEY: I had good access, not superb access. I had access in terms of interview time, and I went out to dinner with him, and I spent some time with him in his office, and then I sort of followed him around a bit, which is normally how I do these kind of pieces. I didn't have fly on the wall access, in other words, sometimes subjects of magazine pieces sometimes allow you stay in their office while they're negotiating budgeting and hiring and firing. But most sane people don't do that. Like, we want them to -- but I think we got pretty good access, and he seemed interested in doing the piece and he was very cooperative. And also his wife was very cooperative. She was key to this, I think upon.

CAVANAUGH: You were surprised about several things about Governor Brown, in reading your article, you were very surprised by the fact that he doesn't have an entourage.

NAGOURNEY: Yeah. Maybe it comes form covering presidential campaigns, and coming from New York, and covering Schwarnenegger a bit when he was elected the first time. He has, like, no staff. I mean, I'm exaggerating a little bit. And part of that is because the budget has been cut here so much. Part of that is because he's a frugal guy, and part of it is that he just doesn't want it. So we opened the piece with him flying into Burbank right after he'd been sworn in as governor, and maybe of the -- there's a gazillion reporters, and a gazillion camera crews, and he has no staff. He just walks off the plane, just starts walking over and talking to the cameramen. There's like two Stewart guards, I think, and that's it. And he doesn't have speech writer, he never hired a chief of staff, he doesn't -- he kind of does it all by the fly. Now, part of it is that he's been doing it for so long that he knows all this stuff. But he doesn't like people writing his speeches for him, and he's a very hands on kind of guy. It's very striking and refreshing too, I must say.

CAVANAUGH: Now, a lot has been made about Governor Brown's age at 73, he's the oldest governor that California has ever had, and looking this up, he's the oldest governor currently serving in the United States.

NAGOURNEY: Is that true?

CAVANAUGH: What did he tell you about his age.

NAGOURNEY: He was kind of frank about it. Now, I covered him when he ran for president in 1992, what was that? 20 years ago? I see the change. And it's not denial. He's not ridiculous about it. He says he feels his age. He says he's not as young as he once was of he's a lot bit slower, he can't run as long, and he can't go twice as much. And you lose a teeny bit of your edge. But a couple of legislatures I talked to said about him, I hope I'm that way when I'm 73. He's in good shape. And he does work out all the time. I'm not a doctor, so I shouldn't do any kind of diagnosis, but he seemed incredibly mentally fit. A great memory, very aware of what was going on. He seems as sharp and energetic as any other person I've ever covered.

CAVANAUGH: I'm speaking with Adam Nagourney, he's Los Angeles bureau chief for the New York Times, and author of the recent profile piece called Jerry Brown's last stand. You also sort of compare him in style with his predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger. What is that comparison like?

NAGOURNEY: Again, with Schwarzenegger of course it was all big entourages, and he had a -- I think his Conan the barbarian sword in his office. And it was all very much into the sort of ceremony of being governor. I'm not making any comment of when he was governor, but just this sort of trapping to the governorship. And he'd show up in an event, he would show up at an event and have a three-car motorcade, and he has all these guards and stuff, and part of it was probably because he's a celebrity, so he probably was concerned about security, and people coming up too close to him. But I think part is they're just sort of different that way. That's the first part. The second part is dealing with the legislature. I think Schwarzenegger never was comfortable and never arguably made that much of an effort to get along with the California legislature. He came out of a different world. He came out of Hollywood, he came out of acting. He didn't really know all those people. He didn't really spend time in Sacramento. Governor Brown in his own life, formally as governor, attorney general, don't forget his father was good afternoon. He knew sort of the way the system works. And I can that he has a respect for the system, and I think that he has made a system, and here I will contrastim had with governors in the country who are more combative these days, in Wisconsin and Ohio, that it is important to be more collegial and getting through to negotiation, and treating people decently, and not trying to fight people down. That's the big thing. And the question is, is that gonna work, 'cause so far it hasn't. So far he's been unable to get his tax suspense plan on the ballot and approved by voters.

MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Right. And Governor Brown in this piece at dinner and other places talked to you about some of the changes that have taken place in state government since he was first governor in the 1970, and it doesn't sound like he's pleased with those changes?

NAGOURNEY: No, his feeling is that the system has changed for the working it's more polarize said, it's more partisan, it's more ossified. I think that he thinks that term limits have really had the opposite effect of what they were intended to have. I'm not sure he's the first person who made that observation, but he sees it up close. But he see people who -- legislators who are thinking about the next office they are gonna have to run for and less time learning the business. And there's less of a premium on building relationships and being collegial. And I think that makes it much more difficult for him to deal with things. There's also the voter initiative system which I think is much more extensive than it was when he was governor last time. There's now a 2 third requirement to get tax -- a tax increase through. It just becomes a much more difficult world to live in. And I think he's just struck by general how partisan and divided Sacramento is.

CAVANAUGH: Right. I get that sense from reading the profile piece. And it even says that the governor was somewhat surprised by the fact that he was not able to get agreement on this special election.

NAGOURNEY: Yeah, you know, I think he was. I think he actually genuinely believed, this is based on his last time he was here, that other legislators shared with him his concern where the fiscal state of California, that he had come up with a program that was balanced and fair. In other words basically half cuts and half tax extensions that included something that both sides hated and both sides liked. And it seems sort of eminently rational to him, and I think he's aware, a lot of the legislators are aware of the depth of the cuts that would have to take place without these tax extensions, and I think he was just surprised that he just couldn't get four votes. I think he really thought he could. He still might I guess, eventually. But I he think just didn't expect it.

MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: We're speaking about the profile piece in the New York Times magazine called Jerry Brown's last stand, written we my guest, Adam Nagourney. Now, you say Governor Brown may be considering a harsh, what you call even a subversive notion, known as plan B. And much has been made of the fact that the governor did not have a plan B in going into trying to get this special election on the ballot. But you suggest from what he's been saying that he may have this -- as I say, this harsh man. What did he suggest to you that he might do?

NAGOURNEY: I think, I want to be clear here not to say that this is what he wants to happen, but I think that he is looking at the landscape and what he's basically saying is that he would argue that government is a good thing, that there are good things about government, about any kind of abuses and problems there are. And he would argue that government needs to be funded, right? Whatever programs we have here in California and across the country costs money. Education, security, police, hospitals. And there's such animus toward taxes right now, as he says is not gonna change any time soon. I think it's much worse even when he was governor, when prop 13 passed. Perhaps the only way to get people to sort of change their minds about taxes and government is to go ahead with these cuts, in other words to let people experience the kind of cuts that would be required here in California that those tax extensions, which I think is about $15†billion, that's a lot of money, and I guess for that matter, what's being considered in Washington and other states. And will as he says, it will be wrenching 678 in other words, people will say once and for all what they get for their money, and what the cost is for those kind of cuts, and maybe that's the only way to get people to say, well, maybe we do want government, or maybe we're willing to pay taxes. So I think that he has a sort of realpolitik realization sort of goal. I'm sure he doesn't want that to happen, but I think that's not a crazy idea, you know?

CAVANAUGH: Yeah, what did he say that made you think he was considering that option.

NAGOURNEY: He just said -- we went through that whole conversation. He said, you know, we're not gone that get taxes passed obviously. So maybe we just have to go through this. Maybe we have to sort of let people experience what it would be like to have these kind of cuts go through. Because it'll be very wrenching, and then they'll be able to appreciate what the value of government is.

CAVANAUGH: Now you say in the article that a plan like that, if indeed the governor were to go and make that harsh plan for California, might make California once again a national laboratory. What do you mean by that?

NAGOURNEY: In other words, like it's -- if you look at this as a way of testing how people would respond to those kind of deep cuts, and who people in effect will sort of recoil and say, no, we do want some government, and we are willing to pay some taxes, that way we can se in California an experiment the way we've seen here in other parts over the past 20 years, a different way of viewing government, and a different way of what works and what does not work.

CAVANAUGH: Right. Once again California taking the lead. We haven't seen that for a while.

NAGOURNEY: Yeah, for sure.

CAVANAUGH: Now, I want to go back to the more personal aspects for just a minute of your article. You introduce us in a very personal way to Governor Brown's wife and Gus Brown. How do he and his wife work together?

NAGOURNEY: Really well. I'm sort of sensitive to this because I covered a lot of political marriages, the Clintons or John Anderson and his wife. And these guys just seem like genuine, like, friends. She's there and Gus Brown is there pretty much all the time. I don't think I can over say how much she's involved in his professional life. She's an assistant, special assistant to the governor. She's involved with all the staffing decisions, she's involved with all the how do you put out the budget decisions. You don't get sense of her being one of these mythical overly strong first ladies, like Nancy Regan you read about in the White house in the 80s, but just a strong, calming presence next to him, the governor. She did not want him to run, she told me. But she wasn't gonna, like, throw herself on the track. Her feeling on this was why do it? I think if it was up to her, she'd be, like, well, why do not we thought sort of retire and enjoy the world? But she's I think supportive of everything he wants to do. And I think their politics are alike. Maybe she has very similar goals. But comparing him now to when I sort of knew him back in the 90, he seems much different. And I do think a lot of that is because of her. And again, I don't want to play doctor, psyche on analyst here. Who knows? But it seem that she really does -- has grounded him and brought him down to earth, and is just a good presence in his circle. But when you're with them, they are clearly very close, and it's very enjoyable. Always nice to watch a couple sort of error close, and they are.

CAVANAUGH: Now, the title of your piece, Jerry Brown's last stand, does that refer to more than the fact that Jerry Brown probably will not run for office, that perhaps this is his final foray into politics?

NAGOURNEY: Yes, I think that's true. I mean, I think he'll probably -- who knows? My guess is he'll run for reelection, when his term is up. And then after, that he'll be what? 78. Even Governor Brown has retire some time. And I don't know what else -- unless he's gonna run for accident like, some mayor of some small town, which, honestly, I would not put that beyond him, I think this really is his last stand. And I think part of it here is there's an element of him coming back and seeing that he has an opportunity to take the state, which I think he genuinely love, 'cause he really is a part of it, and sort of get it back on track. Because I think the state's in really bad shape right now, in a historic way, and I think he appreciates that and really sees a chance to be a historic governor and turn things around. And whether he can or not Sa whole other question, but I think that's what his thinking is right now.

CAVANAUGH: And finally, Adam, let's of us, most of us don't get any time to have I sit down dinner with the governor, and spend time with him. Is he a pleasant person to be around, or is that frenetic energy a little disturbing?

NAGOURNEY: I'm from New York, so I'm all frenetic energy. To me of course frenetic energy is a good thing. The first time I had dinner with him, I think he was a little distracted and defensive. But the more -- but the more I spent time with him, the more I enjoyed spending time with him. And you gotta remember, when you're a reporter sitting down with a subject, and I think the course of all the time I talked to him, I think he went off the record for, like, a minute. Which is terrific. But again, he's a politician. So to a certain extent, he's letting me see the face that he wants me to see. He's aware that wee running a story for the New York Times. So I'm not gonna say I'm sitting here and say I'm seeing the real unvarnished Jerry Brown. That said, just form talking to a lot people and his friends and people who are around him, I think that's a pretty decent approximation of what he's like. And the question is, is he someone that you'd want to have dinner with one Friday night? And my answer to you would be yes. He's an interesting, smart guy with lots of history and fun. But he eats brussels sprouts. I hate brussels sprouts.

CAVANAUGH: Oh, yeah, brussels sprouts, that's a problem. Adam, thank you.

NAGOURNEY: Thank you so much.

CAVANAUGH: That's Adam Nagourney, Los Angeles bureau chief for the New York Times. If you'd like to read the whole article, it's called Jerry Brown's last stand. If you would like to comment, please go on-line, KPBS.org/These Days.