Concetta Antico got her first set of oil paints at the age of 7. Art has been in her life ever since.

"I painted album covers, in my teens, on the walls of my room," she said. "I was immersed in the garden all the time, making little brews of flowers and soil. And really seeing the color in all of this."

Antico didn't realize it at the time, but the colors she saw in that garden could be invisible to the average viewer. By allowing scientists to study her vision and her genetics, Antico learned it's possible she's seeing colors most people can't.

Antico grew up in Australia, but now calls San Diego home. At her studio in Mission Hills, she teaches oil painting and works on her own canvases, all of them popping with color. Color that sometimes seems out of place.

She paints Balboa Park with accents of purple and the night sky with glimmers of orange. Antico said she's using these colors faithfully. To her, they actually appear out in the world.

"I am trying to portray what I see. Over there, there's a painting of a duck," she said, pointing to a canvas hanging in the corner of her gallery.

Strokes of orange and purple outline the ducks' feathers and thin green lines halo their heads.

"Those colors were truly there, in that bird," Antico said. "And they were strong for me."

A few years ago, students and collectors drawn to Antico's unique style started forwarding her articles about a condition she'd never heard of. It had something to do with genetics and the possibility of humans possessing enhanced color vision.

She didn't think much of it. Until she read one piece that floored her. It mentioned that women who give birth to children with color deficiencies could potentially carry the genes for this strange condition. Around that time, Antico's daughter had been struggling to see certain colored markers on the whiteboard at school.

"So I got a pen and paper, and I jotted down the names of the doctors who were cited in this article," Antico said.

She contacted them, and before long, she was spitting into a tube and shipping her DNA off to a lab in Washington state for testing. The results came back. She had the genes for something called tetrachromacy.

"This is a fairly new finding for me, and has changed my life significantly," Antico said.

Let's break down that word, tetrachromacy. Tetra means four, chroma means color. We all probably learned in high school that humans are trichromatic — our retinas have just three color receptors.

But in the past few decades, scientists have been exploring the possibility that some people have four.

How does that happen?

Potential tetrachromats have to be women. Genes that code for color receptors lie on the X chromosome. Men only have one of those, but women have two. That means they could have two slightly different genes on each chromosome, independently producing different receptors. That discrepancy could potentially add a fourth receptor on top the normal three.

"She has a normal form on one X chromosome and this variant on the second X chromosome," said Kimberly Jameson, a researcher at UC Irvine who's been studying Antico's color vision.

The fourth receptor should be similar to one most people have, but shifted to respond most to yellowish, rather than reddish, light.

"This is how she ends up being a potential tetrachromat," said Jameson.

The possibility of seeing extra dimensions of color may sound psychedelic, but look beyond humans, and it's not at all uncommon. Many kinds of birds, insects and fish have more than three color receptors — even up to 16 color receptors. And we know some animals, like dogs, have fewer receptors.

Articles and blog posts linking to Antico's work have claimed she "can see 100 million colors," or that she sees "100 times more colors" than average, or that she possesses "superhuman vision."

But those headlines mask the thorny state of human tetrachromacy research. Jameson and other scientists in this field are still wrestling with a big, fundamental question: Is this fourth receptor really functional? Do women who have it actually see another dimension of color?

Jameson has been putting Antico through a battery of tests to try to answer that very question. It's harder than it sounds.

"Not only do the diagnostics not exist. Any types of tools that we might use, like computer monitors or any kind of display device, they're all based on models that have just three display primaries," Jameson said.

These tools reproduce the world in red, green and blue for a trichromat viewer. But their usefulness for studying people who might be seeing a world built on four primary colors is limited. Even tests that should in theory separate tetrachromats from people with normal vision have not yet delivered definitive results.

There's also the question of how special Antico's genes really are. More than half of all women could be walking around with some form of genetic predisposition for tetrachromacy. But their vision could still be totally normal.

Jenny Bosten is another color vision researcher, currently a visiting scholar at UC San Diego. In one study, Bosten and her colleagues at the University of Cambridge examined more than 30 women with the right genetic profile for tetrachromacy. But they only found one woman who "exhibited tetrachromatic behavior" on every color test given to her.

"Although quite a lot of women have the genetic potential for tetrachromacy, we don't yet have conclusive evidence for anyone that tetrachromacy exists," said Bosten.

Listening to Antico describe what she sees in a dark shadow, it's clear she believes she's seeing colors invisible to most people.

"I see purples, and blues, and reflected colors from other things," Antico said. "It is dark, yes, and it is gray, yes. But it is riddled with subtle pieces of color."

Antico's subjective perceptions are backed up by her objective performance on standardized color tests. She's able to pick out minute differences in color that escape most viewers. But it's hard to know what to conclude from that.

Could it mean that, through years of dedicated art practice, she's simply trained herself to be more sensitive to color? Or is her DNA working in tandem with her training, nature and nurture combining to help her distinguish color better than most? So far, no one knows for sure.

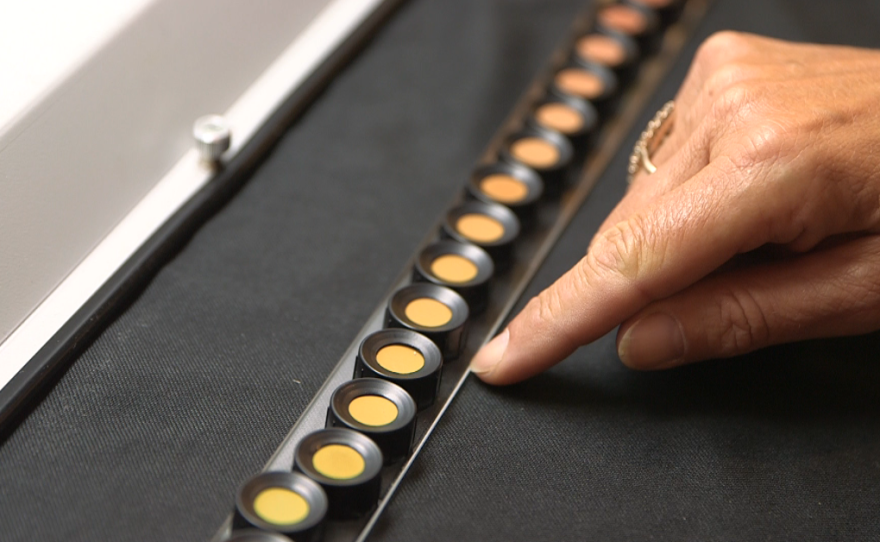

Back at her studio, Antico took another test. Jameson had her look at tiles progressing from pink to green and arrange them into an orderly spectrum. Some of the tiles looked incredibly similar. Even people with good color vision tend to make at least a few mistakes.

When Antico finished, Jameson flipped over the tiles to check the numbers written underneath.

"Perfect, again," she said. Antico had nailed it. Zero mistakes.