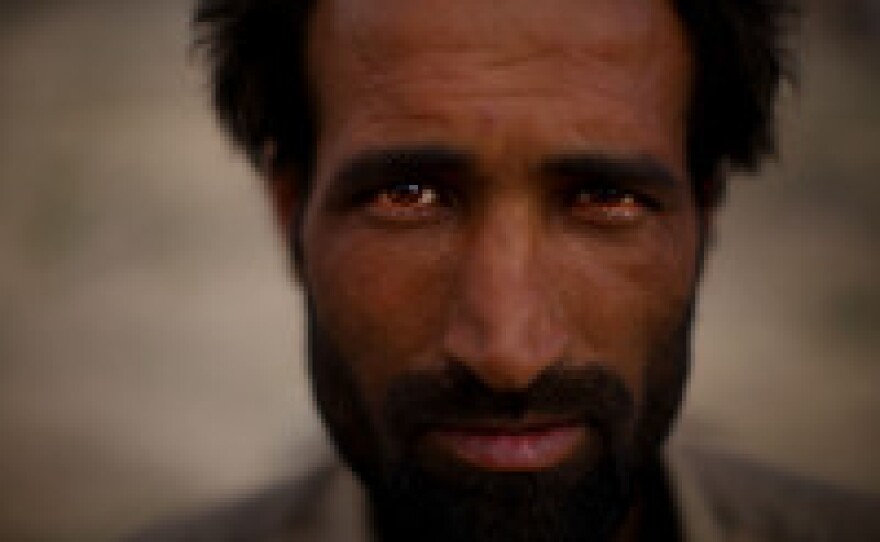

A man sits near the entrance to Kamar Kulagh, just outside Herat and near the border with Iran. The wars and upheavals in Afghanistan over the past three decades have contributed to the widespread use of drugs.

In a dusty ravine on the outskirts of Herat, a scruffy 20-year-old named Ahmad is striking a match to inhale heroin. That's how most heroin addicts get their high in Afghanistan.

Once part of the Persian empire, Herat was considered Afghanistan's most graceful city, known for its exquisite blue and green glass and its many poets.

Today, one of its distinguishing features is this village of drug addicts where Ahmad and other live on what's been a dumping ground for refuse from building sites in this western city.

Hundreds of addicts have dug out small caves that honeycomb the hills, each one encircled by chunks of crumbling cement.

Ahmad's mother Zahra leans against some rocks in front of their place. Her flat, gold eyes peer at us from beneath a plaid veil as she tells her story

"I used to weave carpets and also worked as a maid," she says. "Then my husband got cancer and died."

Zahra's life spiraled downward, hitting bottom when her sister-in-law, returned from Iran and offered her heroin.

Now, Zahra says, "I can't do anything except beg on the street."

We pull back a red cloth to find another woman, Zahra's sister, blinking up into the light. In the center of this tiny space is a cooking area — not for food, but for heroin.

There's also a small figure moaning and moving restlessly under a filthy blue burka.

"That's my daughter," says Zahra.

She's 10 and she's hooked on heroin too. How did such a young girl become addicted?

"When we had my sister-in-law living with us, she was addicted," says Zahra. "I would go out to other homes to do housekeeping. And my little girl Laila used to cry a lot. So my sister-in-law gave the child opium to calm her down — that's when she became an addict."

Zahra says her daughter has already gone through rehab at a clinic in the city.But once back in this drug village, the 10-year-old became addicted once again.

Few Resources To Combat Drugs

In a white-tiled office, Dr. Ezmaray Hassin runs several clinics in Herat, and he says one of them serves children as young as four. There are an estimated 70,000 drug users here now, he says.

"There's no doubt that Afghanistan is one of the largest producers of poppy, but historically they have never been drug users," Dr. Hassin says. But more than three decades of war, which has displaced millions of Afghans, has created all sorts of upheavals, he says.

"A lot of people travel to the neighboring countries, and they got to know about narcotics," he adds. "And the one country that's closest to Herat is Iran.

Iran has long had one of the highest rates of drug addiction in the world. Traditionally, heroin has been the drug of choice, but recently there has been a dramatic rise in the use of crystal meth.

Sitting on a bed in this clinic is Saleh, 25, who tells a story we hear again and again.

A few years ago, he crossed the border into Iran to look for work.

"I was in Iran and I was digging wells," he begins. "Then my legs would really, really hurt, really bad. Basically it started with opium first to treat my legs — to kill to pain. Not heroin. And then over time I went to heroin. Then the problem became that every time I did not use heroin my legs even would hurt more. So I had to use."

Relatively speaking, Saleh is among the lucky ones. There are just 250 beds devoted to drug treatment in all of Herat.

The city's top counter-narcotics officer is Faquil Gul Amini, whose office in the center of Herat is protected by trucks with mounted machine guns.

Amini's resources are limited and the challenge is growing with the arrival of a drug he'd never seen before a couple of years ago: crystal meth, which is known in Persian as shisheh, or glass.

Amini says he has just raided meth labs in Herat and arrested a Breaking Bad kind of guy from Iran. But he has no illusions about the magnitude of the battle he faces.

"I'm afraid to say when it comes to the list of priorities for the government to deal with, the issue of drug addicts, I'm afraid to say it's below zero," he said.

Which is why this village outside the city is full of addicts. On a hot day you can see a constant flow of men walking up and down on a path crunchy with broken glass.

They are going nowhere.

Those who are on crystal meth are easy to spot. One we encounter has the air of a 60-something hipster. A trim gray beard. A black leather jacket. A tattoo on his hand spelling love.

His name is Haji Ismatullah, and the young men clustered around him call out, "He's a writer."

As evidence, he opens a notebook filled with elegant Persian script in red and black. "I say poetry for the people here," he says.

Ismatulah says he began using crystal meth after his wife and three children were killed in a car accident.

"My heart was hurting a lot after the accident when I lost my family," he says. "Some people told me if you take meth it makes you forget things. And there's a lot in Herat, so I took it."

For the first few months, it did help, he says. But, he adds with a cackle, "After that, it does not help me because it's not a good friend."

Still, Ismatullah would like some meth right now.

As we walk with him to his place, a young woman who carries herself like a dancer comes toward us. The men see her and laugh. She has lost her mind, she's crazy, they say.

She does in fact call herself by the name of a famous Iranian singer and seems to think she's on stage. Decked out in a magenta cape, turquoise beads, and a turban, she tosses her head dramatically and with a kind of wild beauty.

Then she spins away, just as we reach the dwelling of Ismatullah, which resembles a stone igloo.

He goes inside the tiny place and smokes crystal meth in a glass pipe.

Afterward, he's ready to wander again, so we walk to the top of a hill to a makeshift cemetery. He takes us to a fresh grave marked by a small mound of rocks. There lies his friend Baluchi, who has just died.

It's a moment that brings to mind a question we put earlier to a man named Mohammed, who had lived in this drug village for six months. I asked him what his future was, and he replied: "Look at my life, this life. The end for us is death. That's what we're waiting for."

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/