The massacre of 15 young people at a birthday party in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, in late January is being seen by some as a turning point in the country's drug war.

President Felipe Calderon initially dismissed the incident, saying the dead teenagers were probably gang members cut down by their rivals.

But they weren't young thugs. Most were students, and the youngest victim was 15.

Calderon has since apologized to the families. He has traveled to Juarez twice since the massacre and pledged to pump millions of dollars into civic programs in what has become one of the world's deadliest cities.

Calderon rarely comes to Juarez, so when he did in mid-February, security was tight. Soldiers in Humvees with machine guns mounted on their roofs guarded the airport. Federal police lined the streets and surrounded the hotel where he was speaking.

In 2009, more than 2,600 people were killed in Juarez as Calderon's forces and two of Mexico's most powerful drug cartels fought for control of the border city.

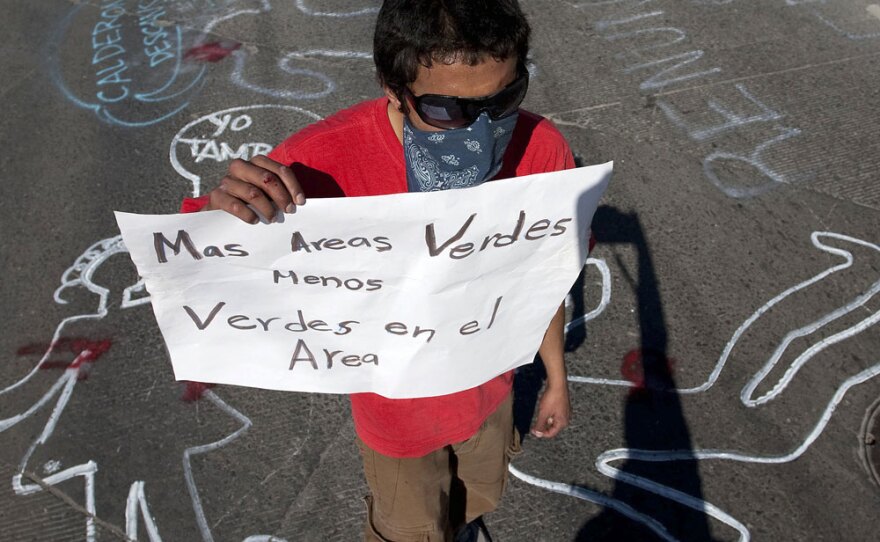

Outside his hotel, a few hundred protesters, many masked behind bandannas, clashed with the police.

Cipriana Jurado was one of the demonstrators. She says Calderon and his administration abandoned Juarez.

"They started a war without consulting the community, and the victims are the community," she says. "We don't want this war. There are executions and assassinations in broad daylight, but neither the army nor the federal police intervene."

They started a war without consulting the community, and the victims are the community. We don't want this war. Here, there are executions and assassinations in broad daylight but neither the army nor the federal police intervene.

In March 2009, Calderon put the Mexican army in charge of the Juarez police department after one of the local drug cartels ordered the police chief to quit.

Calderon now concedes that military muscle alone isn't going to end the violence. "We need to tackle this social plan, because the problems in Juarez have deep roots in the structure of this city," Calderon told a group of local business and community leaders.

Young people lack opportunities, he said. Juarez doesn't have enough schools, hospitals or soccer fields. Only half the roads are paved. Murder, extortion and kidnapping go unpunished.

Calderon said the social fabric and rule of law need to be re-established in Juarez. He received one of his biggest rounds of applause when he declared that motorists should be accountable and people should no longer be allowed to drive around without license plates.

Calderon pledged tens of millions of additional dollars for social programs in Juarez, but he also said he will not pull the Mexican army out of the streets.

The double punch of the global economic downturn and the gruesome drug war has battered the border city across the Rio Grande from El Paso, Texas. The maquiladoras, or assembly plants, in Juarez have cut more than 100,000 jobs since 2008. The owners of thousands of restaurants, bars, corner stores and other small businesses have shut their doors rather than pay "protection money" to local gangs. Many professionals have moved to El Paso.

Alvador Gonzalez Ayala, a civil engineer who works in Texas, has chosen to keep his home in Juarez. "And I want to remain here," he says. "I want my children to remain here."

He says one of the biggest problems facing the industrial city is the huge disparity in wealth.

Gonzalez says much of the blame rests with the local elite, which he says is "a privileged and influential minority that's totally indifferent to the great mass of poor people [who] live in the area."

He adds that the city has been neglected for decades. Young people who see the opulence in Juarez and just across the border fence in Texas are attracted to the quick money of the drug trade, he says. Workers in the maquiladoras earn $60 to $70 a week. Drug runners can earn that or much more in a day.

Gonzalez is involved in several civic groups, and he recalls going recently to talk to a group of preteens in one of Juarez's poorer neighborhoods.

"We were promoting education and science and math. And we were asking them, what do you want to do when you grow up? Many of them told us, 'I want to be a sicario.' That's striking. A sicario is a paid assassin," he says.

Gonzalez and many others say they welcome Calderon's new social plan for combating crime. But they remain skeptical and say any investment in rebuilding the social fabric of Juarez is going to need the attention of the president, not just for a few weeks, but for years to come.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))