If you've been playing video games long enough, you might remember the last time virtual reality was the next big thing. Back when Hollywood channeled their cyberspace obsessions into movies like Hackers and The Matrix, and video game companies promised to transport players into a rich new world of immersive gaming.

Well, the technology wasn't ready to live up to the hype, and virtual reality headsets quickly went the way of Pogs and Beanie Babies.

But it's 2013 now, and virtual reality is back! Headsets have gotten smaller, better, cheaper. That could be good news not only for gamers, but also for veterans with PTSD and people suffering from motion sickness.

San Diego indie video game developer E McNeill recalls that initial wave of virtual reality hype with a smirk.

"I kind of laugh at the movies I've seen now, and how they represent what hacking is," he said. "Where, I don't know, you wave a hand and you've broken through the security or something."

These visions of virtual reality might seem like a '90s throwback. But thanks to a new headset called the Oculus Rift, virtual reality is again attracting lots of excitement.

McNeill made what he describes as a cyberpunk hacking game for the Rift called Ciess. "You're like, in the system," he said. "You're zooming from node to node trying to hack stuff and capture the classified data, presumably for money."

Ciess won first place in a competition put on by the Irvine, CA-based company that makes the headset. And I got to play it.

I entered this 3D virtual space by strapping the Oculus Rift over my head, shutting out the world around me. I positioned its two eyeball-sized screens right in front of my face. When I moved my head around, my first-person viewpoint would move too, making me feel like I was actually inside this cyberpunk universe.

McNeill says he and other developers see the Oculus Rift as the device that could finally make good on the promise of virtual reality. That promise has been broken many times before. One of the highest profile failures was Nintendo's Virtual Boy. It had crude graphics drawn only in red and was notorious for making players nauseous.

"Yeah, this is a step above the Virtual Boy, I can tell you that," McNeill assures us.

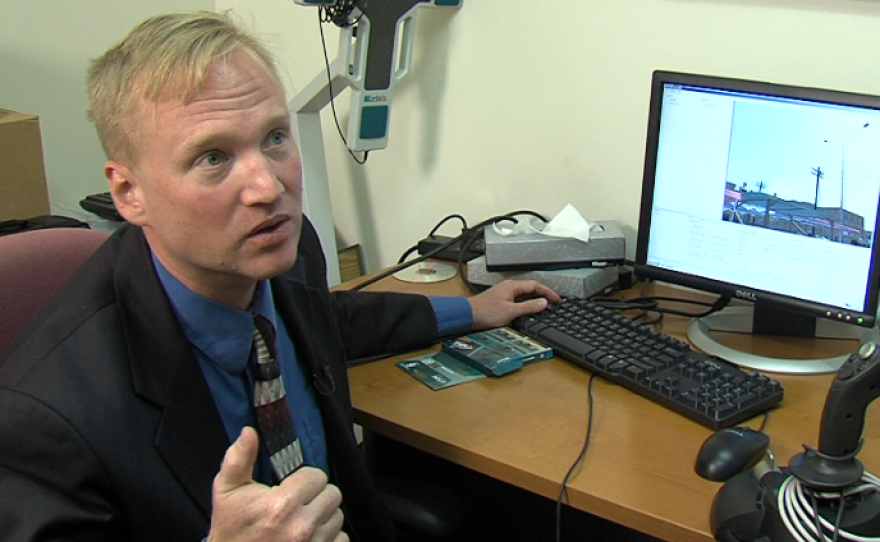

Virtual reality may have gone out of fashion in gaming. But peek inside Dr. Robert McLay's clinic at the San Diego Naval Medical Center, and you'll see it never really died.

"We're using virtual reality to treat post-traumatic stress disorder," he said. "It's a condition that is not uncommon in folks who've come back from combat."

Dr. McLay uses a kind of exposure therapy to help soldiers returning from combat cope with their trauma. The idea is people can learn to deal with traumatic memories after being gradually exposed to what caused them

Of course, Dr. McLay can't send his patients back into Middle East combat. So he uses a virtual reality headset to simulate Iraq and Afghanistan.

I strap on the headset, grab hold of a mock M16 rifle, and Dr. McLay shows me how the treatment typically works. I'm looking out onto a nondescript Iraqi outdoor market with some citizens and soldiers milling around. For the moment, everything's peaceful. But Dr. McLay is about to set off a car bomb down the street.

"Let's set the trauma now to severe," he said, indicating that this scene would come pretty late in his PTSD therapy regimen. "We'll blow up this car."

Then comes a loud boom and accompanying vibrations beneath my feet. All of a sudden, the avatars of people who were standing near the car now lay maimed beside the smoking wreckage. I hear screaming and gunfire in the distance. I know this is all just a simulacrum, but it's still quite intense.

I could see how being inside this headset might trigger a veteran's PTSD. But I could also see that the graphics, circa 2005, are getting kind of outdated. Dr. McLay hopes that all the advancements being made in video games will trickle down to clinics soon, just as they have in the past.

"If we had to build it up from the ground, without the video game industry already working on these issues, it wouldn't have been possible," he says.

UC San Diego's Dr. Erik Viirre agrees, saying, "Without the gaming world we wouldn't be where we are."

Before coming to UC San Diego as a neuroscience professor, he did some work in the '90s for a company called Virtual i-O. They made an early commercial virtual reality headset that sold a decent number of units—but not enough to recoup the huge up-front development costs.

Dr. Viirre had more success developing medical applications for virtual reality. After landing at UC San Diego, his research showed that virtual reality headsets could treat people with inner ear disorders that disturb their sense of motion.

"They can't keep up with the world," Dr. Viirre explains. "The beauty of virtual reality is I create the world, and I can make it move the way I want."

Basically, virtual reality can overcorrect for someone's balance issues in real reality. Now Dr. Viirre hopes newer, cheaper headsets could find other applications for different diseases.

"If we build a cognitive prosthesis for somebody with Alzheimer's disease, but it costs $100,000, that'll never work," he said. "But if we can use the $500 game system, now we're talking about something that could make a huge difference in people's lives."

For now, the Oculus Rift is only available to game developers. Oculus hopes to ship the headset for consumers sometime next year.