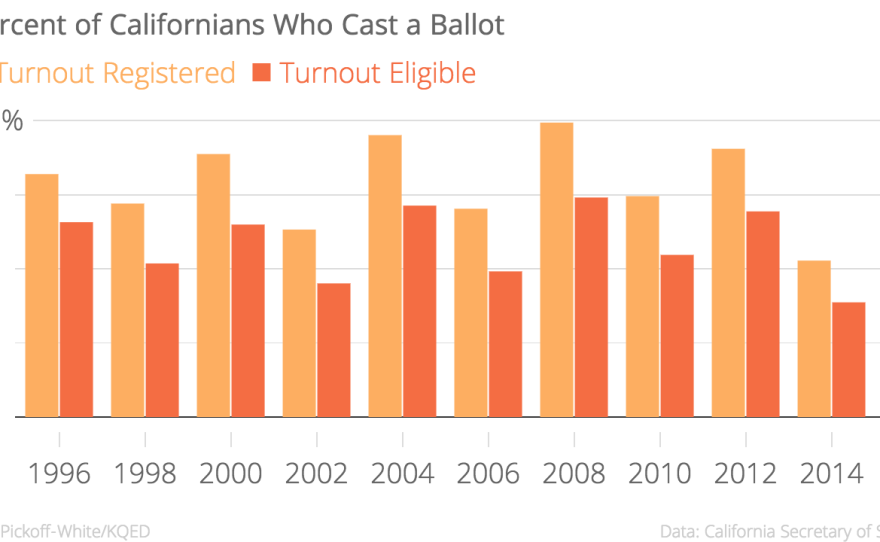

California is first in a lot of things, but voting isn't always one of them. In the last election less than a third of eligible voters cast a ballot.

And for one of the most diverse states in the country, it’s still an older, whiter and wealthier group of voters who show up for Election Day.

To get a ground-level look at what is on the minds of Californians this election year, four California public media newsrooms are teaming up.

Reporters from KQED in San Francisco, Capital Public Radio in Sacramento, KPBS in San Diego and KPCC in Los Angeles examined voter turnout records to identify communities where many people are opting out of voting and communities where getting in a ballot is a priority.

Throughout the year we'll be following a handful of communities, asking about the candidates, issues and circumstances that either drive people to the polls or keep them home on Election Day.

And we'll explore other ways, besides voting, that Californians are engaging in the civic life of their communities.

Many people say their vote doesn't count

Our first stop is the South Los Angeles community of Watts just south of downtown L.A.

Once a stronghold of African-American life and culture, Watts has changed a lot in recent decades. Many black families fled in the aftermath of riots in 1965 and 1992, or to escape gang violence and find work and cheaper housing in other places, like San Bernardino to the east or Lancaster in northern Los Angeles County.

Watts remains one of the most densely packed sections of L.A., thanks in part to new Latino and Asian families moving in. Yet most voting precincts in the Watts area saw fewer than 22 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot in the 2014 general election.

“I voted in the past, but votin’ it doesn't mean nothing,” says 29-year-old machinist Samuel Price as he waited to catch a bus to work.

Price doesn’t vote now. When asked if he might find himself charged up over a controversial proposition or firebrand presidential candidate, he doesn't hesitate to answer.

“Nobody, none,” Price said. “The political process to me is all a big game; it’s all corrupt, it’s about money.”

Bus driver Walter Flowers does vote. He says he leans conservative; the economy — higher wages specifically — is foremost on his mind.

“It’s the poor people that are the main source of the labor in the city. Without that blue-collar labor, a lot of L.A. will not run right,” Flowers says. And, he added, “Anything that depletes money from my pocket to Washington, D.C., that's what bothers me.”

In fact, the majority of Watts’ residents fall below the poverty line.

In Meadowview, a predominantly black and Latino neighborhood in Sacramento with middle-to-lower-income residents, about 45 percent of registered voters submitted a ballot in the 2014 general election.

But skip over Interstate 5, the dividing line between Meadowview and the neighborhood of Pocket-Greenhaven, and it’s a much different story.

Sculpted lawns, monogrammed gates and private lakes line the main roads, while young families gravitate to the suburban homes at the Pocket's center. Residents like Ellen Broms speak knowledgeably of the upcoming presidential elections.

“I vote every time. (But) I don’t necessarily work for a candidate every time,” said Broms, sitting on a concrete bench at a dog park squarely between the two neighborhoods.

Now in her early 70s, Broms has voted in every election since she was 19.

“It maybe doesn’t seem like it makes a difference, but I always look back and think you plant a seed, and you have to look at the long view,” Broms said.

In contrast to Meadowview, almost 60 percent of the Pocket’s predominantly wealthy, white registered voters turned out for the November 2014 election.

“We can't ignore the linkages and the parallels between poverty and wealth, versus turnout rates,” said California Secretary of State Alex Padilla, who grew up in the working-class suburb of Pacoima north of Los Angeles.

Padilla said many of California’s unregistered and most disenfranchised voters live in communities like Watts or Meadowview.

“Disproportionately communities of color, disproportionately younger people, disproportionately working-class families,” Padilla said. “And so what are the reasons for that?”

Among eligible Californians between the ages of 18 to 24, only about 8.2 percent voted in the 2014 general election, according to a UC Davis study.

Eduardo Marcos, 22, a student at Sacramento City College, said there's just no point to voting.

"Basically, the stuff I hear is the same thing I’ve heard over and over the years. For example, we got wars, we got the economy going up and down," Marcos said. "It’s just the same things I see forming, but no one’s really solving anything."

'We depend on her, for our vote to count'

About an hour south of Fresno, in the town of Lindsay, the Medellin-Huerta family is trying to persuade one young family member to vote this year.

Luis Medellin, 29, can't understand why his 18-year-old sister, Amy Huerta, doesn't vote — and he's trying to convince her why it matters.

“I’m pretty sure you’re registered to vote, when you turned 18,” Medellin tells her. “Are you going to vote?”

“I don’t know,” laughs his sister nervously.

“I feel like sometimes my vote doesn’t count,” said Huerta, echoing the sentiment of countless voters across California. “Especially because right now, (my) generation is at a point where they don’t care.”

Amy’s brother does care, and lobbying his sister to get out the vote isn’t his only cause. Medellin also works as an activist on the issues of pesticide use and air quality in his community.

But here's the rub: Medellin doesn’t vote either. He can't. He was born in Mexico and doesn't have legal residency. Neither do his parents. But Amy was born in the United States, and her brother feels she has an obligation to exercise her right to vote as a U.S. citizen.

“Amy is our family’s voice. Because myself, I don’t have legal status, my parents don’t have legal status,” Medellin said. “We depend on her, for our vote to count.”

There probably aren’t many elected leaders who understand the value of each and every vote more than Ramona Villarreal-Padilla, the mayor of Lindsay. Of her roughly 12,000 constituents, only about 2,000 are registered to vote.

“I think that I won by maybe 50 votes.”

Lindsay is set amid acres of lemon and orange orchards in Tulare County. Citrus is king here. But the people in this rural, working-class community often feel disconnected.

It’s how Villarreal-Padilla sometimes felt way before she was mayor, when she was a kid.

Her father was a farmworker who marched with labor organizer Cesar Chavez. “But my dad, if he left anything for us to know, he said if you don’t vote, or don’t register to vote, then the government will take your voice away," Padilla said.

And there are a lot of muted voices out there: nearly 7 million eligible yet unregistered voters in California, according to the Secretary of State’s Office.

Those are the people Alex Padilla is trying to reach with a new motor voter bill he spearheaded last year to increase the number of registered voters.

“But registration is just half the battle,” he said.

“Only 42 percent of registered voters turned out in November 2014. How do we get them to the polls?” Padilla asked. “Well, reforms (like) mailing every voter a ballot every election and providing flexibility in when, where and how to cast a ballot. We know from Colorado, turnout is up 20 percent since they instituted these reforms. And I think it can work for us here in California.”

Working to engage new voters

There’s also the tried-and-true method of walking the precinct block by block, door to door, day in and day out.

That’s what Debora Samuels does as a volunteer with the San Diego Organizing Project, a faith-based group working to boost voter turnout.

Samuels focuses on the sprawling San Diego neighborhood of City Heights. It can use the attention, with less than 20 percent of registered voters actually casting ballots in recent elections.

More a small city within a really big city, City Heights captures the quicksilver demographics of Southern California. About 75,000 people live in City Heights, nearly half emigrating from countries outside the U.S.

“You can find from Latino, Vietnamese, African like from Ethiopia,” said Samuels, rattling off a sampling of the ethnic mix.

She herself was born in Panama and resettled in City Heights 20 years ago. It's among these new immigrants, the ones who like Samuels will eventually become U.S. citizens, where she and others find hope for the electoral process.

“When they first get naturalized they are excited, because they can vote, they can ask for what they want,” Samuels said. “But I guess down the road when they see things not changing, that’s what brings them down. And they get disinterested.”

It’s an all too familiar caveat that at least in recent elections suggests a civic crisis for California.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misspelled Debora Samuels' first name. Also, the last quote in the story was incorrectly attributed to Secretary of State Alex Padilla. It has been changed to reflect that Samuels said it.

Copyright 2015 KQED. To see more election coverage, visit kqed.org/election2016.