On Monday, San Diego Unified students returned to class for their first day of the new school year. With the excitement of school comes the reality that many children are still feeling the effects of extended school closures during the coronavirus pandemic.

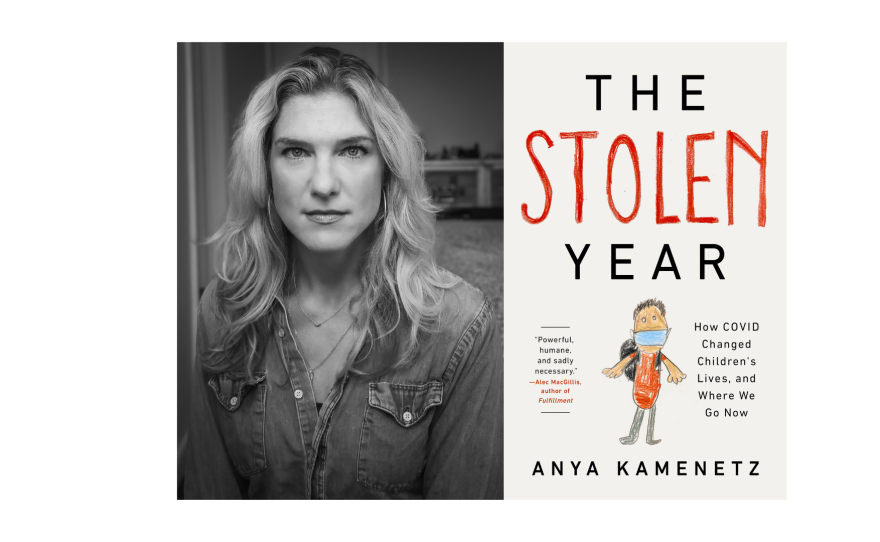

A new book from journalist Anya Kamenetz documents stories of trauma and resilience among students and their families. Kamenetz joined Midday Edition Tuesday to talk about her new book The Stolen Year: How COVID Changed Children's Lives and Where We Go Now. The interview below has been lightly edited for clarity.

Q: In your book, we hear from kids and families from a wide variety of backgrounds all over the country. What is the common thread you found?

A: Two things I would say: One, is that they (kids and their families) were stretched to a breaking point by the various stresses of the pandemic — economic, social, the fear, the political division; and the other thread, of course, is the love. I mean, every family I talked with, as hard as it was, they found solace in being together even during the darkest parts of this pandemic.

Q: What do we know today about the impact of the school closures and what it did to children?

A: We know it's going to take several years for children to resume the test-score trajectory that they were on before the pandemic. That's an average. Obviously, some kids are fine right now, and some kids might never catch up.

We also know that there's been a huge downturn in public school enrollment as well as in college-going. Some of those kids are home-schooled or they're in private schools, and they're going to be fine. But some of those kids have dropped out and they have drifted into paid work, and that's very bothersome for the future of this country.

Q: In your introduction, you write that you were thinking of this book as "a little like restorative justice or therapy." Why do you feel that approach was the best way to tell this story?

A: I just feel like we tend to rush past the pain of kids because it is painful for us. I mean, everybody who has a child understands that you're affected differently by the sound or the sight of a suffering child. And unfortunately, that sentiment oftentimes leads us to not pay attention to what is actually happening.

So, I wrote this book to make sure we took a good, hard look at what happened to kids during the beginning of this pandemic. And with that hope in restorative justice comes figuring out what the harms are and how to address it. And in a therapeutic context, you start talking about what happened because, again, that's going to help you identify how you're going to feel better about it.

Q: So, we have been here before in the sense that your book talks about other examples where schools were closed down and the impact. One of those was in New Orleans after hurricane Katrina. Tell us what happened to those kids.

A: Yeah, so I was down there as a young reporter. I went to high school in New Orleans as well, and what we found is that kids were out of school, usually for a few weeks. The public schools in the city shuttered, were closed for the fall semester of 2005 and mostly never reopened because they were all replaced with charter schools.

Over time, those kids suffered extreme academic setbacks that took a couple of years, actually to recover the ground that they lost even though they weren't out of school very long. And the impact on youth in general, we saw a downturn in college-going, a downturn in high school graduation rates that persisted for up to a decade after the storm.

Q: Your book talks about schools are much more than just places of learning, but also essential for food and nutrition, child care and health care. Do you think that government and school officials could have done more to fill those gaps while schools were closed?

A: Absolutely. They could have and should have. I point to countries in Europe that despite the fact that they struggled as well with the pandemic and various ways of the pandemic, they made a concerted effort to prioritize children for reopening.

And that's exactly what we never did in this country. We obviously had red states that opened everything up with almost no precautions, and then we had blue states that allowed our bars and restaurants to be open while schools and day cares were shut. And that's the part that's so hard for me to understand, not only as a reporter, but as a parent.

Q: You profile students with special needs who are especially impacted. Tell us about them.

A: Fourteen percent of kids have disabilities. It's not some tiny margin. And for the most part, what families told me was that Zoom was not an effective delivery system for the education, the socialization, and the therapies that those kids needed.

And what you see with kids with disabilities is that not only do they not make progress, but they can go backwards, they can regress, because these are developmental disorders and they follow developmental pathways. And so we're seeing so many struggles. And with oftentimes the school struggles and the social struggles come mental health struggles as well.

I mean, one of the most heartbreaking families that I talked with was a child in Hawaii, and she had multiple severe disabilities. She was autistic and nonverbal, but she loved school and she was in a mainstream classroom. Her classmates surrounded her with love and affection. When she was cut off from all of that, she had no real way of understanding why, and she became horribly depressed and regressed in a number of ways. And her mother says that she's never been the same.

Q: There is another population that you address, and that is students along the U.S.-Mexico border closer to home here in San Diego. Tell us about the experiences of those children.

A: Yeah, I mean, this would have taken a whole other book, and I hope that there is another book out there. But as we know, MPP, the Remain in Mexico Policy created a really upsetting situation on the U.S. Border. And occasionally migrant children who did cross the border during the pandemic were quarantined all by themselves. So, it was a really awful situation. And the long-term issue as well. Obviously, there's been an interruption in kind of immigration patterns and so we're seeing that now with the flow of kids over the border and trying to resettle them and reintegrate them.

Q: You say in your book that the story is not over. So, like the title of your book asks, where do we go now?

A: I would love to see renewed emphasis on the well being of children and families in our politics. It was really disappointing when the Inflation Reduction Act was passed. It was a huge Democratic victory on climate and on health care. But they left out the provisions that had been in Joe Biden's broader agenda when it came to children and families.

And a lot of people thought this was going to be the moment that we'd finally get subsidized child care, federally guaranteed paid leave and a child tax credit. So I really hope that those — I don't just hope that I would exhort anyone who's paying attention to politics and wants to get involved to say, this can't wait any longer.

Q: I'd like to end on an encouraging note. Where is the hope in this situation?

The hope is always going to be found in the love for kids and the fact that kids have a chance to grow. And all of the families I followed during the pandemic, they all felt that there were silver linings and simply being able to be together when the world stopped.

I hope that we all kind of get a chance to keep that in mind as we go forward to a more normal and a busier world, that there's something really magical about being able to be together with your loving family when you can.