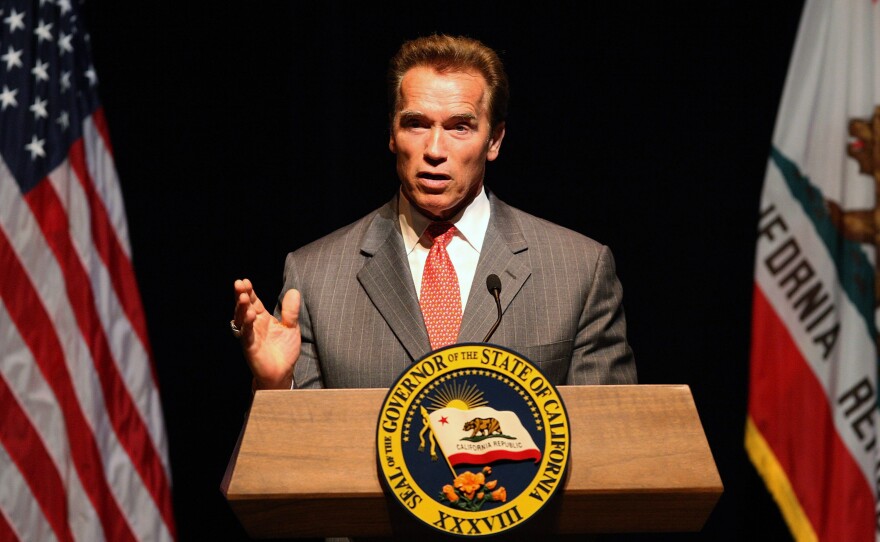

To hear Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and state finance officials tell it, July 28 is California's last stand before fiscal Armageddon.

Top financial officers say that's when the state will run out of sufficient cash to pay all its daily expenses unless lawmakers pass a balanced budget.

Schwarzenegger has warned that government will come to a "grinding halt." The state controller describes "a meltdown."

But what exactly will happen just five weeks from now is less clear-cut than the dire pronouncements suggest.

California government will not come to a dead stop: California Highway Patrol officers will remain on duty, prisoners will still be guarded, and state firefighters will stand ready to put out wildfires.

Still, many services normally funded by the state, such as local road projects and community health clinics, would either stop or get cut back.

Counties may not have money to run a wide array of social programs. College students who rely on state assistance might have to pay their own fees or consider leaving school.

Dr. Gilbert Simon, owner of the Sacramento Family Medical Clinics, said he could go out of business, forcing his patients to find care elsewhere.

"Anyone who relies on income from a functioning California government is at risk," said Simon, whose facility is the largest privately run health clinic in the region and relies on reimbursements from Medi-Cal, the state version of the federal Medicaid health program for the poor.

California considers Medi-Cal a priority payment, but that does not comfort Simon. The state has reduced payments to his clinic in past years, and he worries that this year's fiscal crisis is so acute that he will not get paid at all.

How did California arrive at this point? The state's budgeting system was strained by years of overly exuberant spending by lawmakers and voters, who expanded or created programs without identifying ways to pay for them. Then the recession caused a sharp drop in sales and income tax revenue.

The result: California's general fund, the state's main bank account, has a projected $24.3 billion deficit for the fiscal year that begins July 1. By the end of July, incoming cash will fall below the state's payment obligations if lawmakers do not enact a balanced budget, either by slashing spending, raising taxes or doing both.

By September, California could be $6.5 billion in the red.

In February, Schwarzenegger and the Legislature adopted a budget for the new fiscal year that was supposed to stabilize California's finances through mid-2010, but a precipitous plunge in tax revenue put the budget out of balance within weeks.

Revenue from personal income taxes, for example, fell by 34 percent for the first five months of the year, compared with the same time last year.

As income starts to drop below the level needed to maintain programs, the state is required to make choices about where to spend its money. Schools and bond holders have first dibs, followed by other debt payments.

State employees, who by law cannot be given an IOU instead of a paycheck, would be next, followed by Medi-Cal and pension payments.

Everyone else such as vendors and local governments will have to wait until Schwarzenegger and lawmakers agree on a plan to bring spending in line with revenue.

"Without clarity on this important issue, it is hard to plan for the future, much less to pass a state budget in bad economic times," Stephen Levy, director of the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy, wrote in a recent memo to reporters.

On Wednesday, the Legislature began debating a Democratic plan to close the deficit, but it did not appear to have sufficient Republican support to pass. Schwarzenegger also said he opposed it because it contained tax increases.

Compounding the problem is California's system of tax collection. Because its budget relies so heavily on the personal income tax, most of the state's revenue arrives in the spring.

In a typical year, that's not a problem. The state treasurer merely gets a low-interest loan to pay the state's daily expenses until tax revenue starts pouring in, and then pays it off.

But without a balanced budget, lenders may not be willing to provide the short-term loan, leading to a severe cash crisis later in the year.

State Treasurer Bill Lockyer says the state needs to enact a balanced budget by July 1 to give him enough time to obtain the loan.

"Another prolonged, embarrassing political stalemate would further damage California's credit reputation, hurt our ability to sell bonds, notes or warrants, and inflict unnecessary harm on taxpayers and crucial public services," Lockyer said last month when Schwarzenegger released his revised budget plan.

Bankruptcy is not an option. U.S. bankruptcy law does not cover states, which have the right to levy taxes and borrow money.

Also on Wednesday, Controller John Chiang said thousands of contractors will start receiving IOUs as soon as next week so California can conserve cash - something the state has done only once since the Great Depression, in 1992.

Paul McIntosh, executive director of the California State Association of Counties, said local governments will bear the brunt of the consequences if state spending is stripped to a bare minimum.

The spending cuts would mean reduced foster care services, fewer deputies guarding prisoners in county jails and delayed road projects.

Schwarzenegger hopes the looming threat of a cash crunch puts pressure on lawmakers to strike a deal quickly. He recently rejected Chiang's proposal for a more expensive loan to fund all state operations while budget negotiations are under way.

The governor told the Los Angeles Times editorial board that such a loan would merely enable the Legislature to delay tough decisions.

He said he would rather "let them have a taste of what it's like when the state comes to a shutdown - grinding halt." The governor later revised his statement, saying government would "shut down by itself."