You may not know the name Homer Laughlin, a china factory in Newell, W.Va., but you'd likely recognize — or have eaten off of — its most famous product: brightly colored, informal pottery called Fiesta.

While most of America's china factories have closed, unable to compete with "made in China" or Japan or Mexico, Homer Laughlin, which set up shop on the banks of the Ohio River in 1873, is still going strong. It employs about 1,000 people.

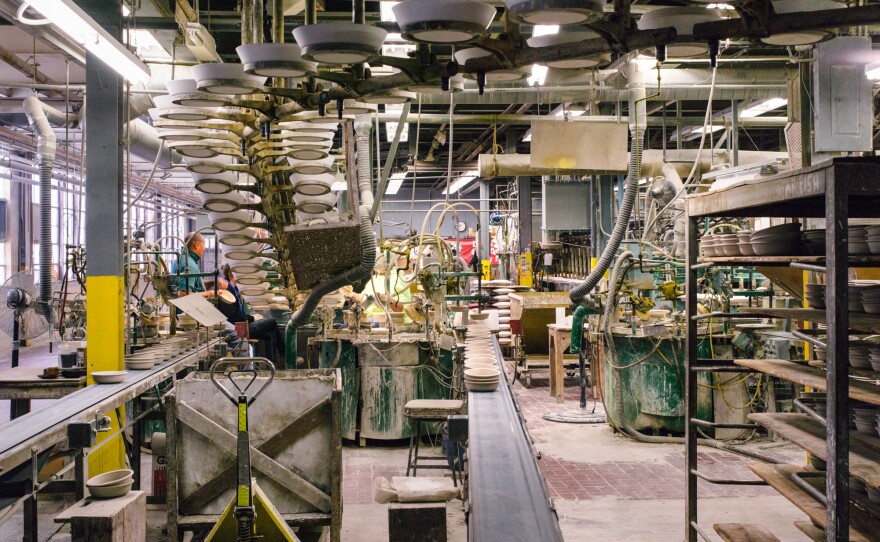

Walk into the big dim factory buildings, dusty and smelling of mud and you might be back at Homer Laughlin's beginnings in the 19th century. People are sitting quietly in pools of light, carefully attaching handles to greenware — pottery that's not yet fired. Decorators are painting bands of color on glazed plates.

"I'm just a hand liner. I put lines on," says Kevin Manypenny. He's been working here for nearly 40 years.

He twirls a plate, dips a brush in brown glaze and paints three delicate lines on the plate's edge. Fiesta is about half of Homer Laughlin's business — the other half is dinnerware for hotels and the sturdy plates and cups you find at chain restaurants. The plate he's working on is for a Boston restaurant.

Manypenny and seven of his eight siblings — and their parents — have worked at this factory. And there are dozens of families like theirs. Brothers founded the company: Homer and Shakespeare Laughlin — presumably a literary family — jumped on a new fashion for a whiter, more refined dinnerware.

"They were the young whippersnappers in the pottery world, and they were the ones who ended up successfully firing four kilns worth of whiteware before any of the other potteries could and then they won a prize of $5,000 ... and that's what launched the Laughlin brothers into pottery production on a big scale," says Sarah Vodrey of the Museum of Ceramics across the river in East Liverpool, Ohio, where Homer Laughlin used to be based.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the factory changed hands. The new team built a plant on the West Virginia side of the river, and those long low factory buildings are still in use today.

Then in the 1930s, the company created Fiesta: inexpensive, colorful, cheerful dinnerware. It was a hit even in the Depression. In 1948, Homer Laughlin really stepped up the production of plates and bowls. The company designed and built its own machine inside the factory. Dave Conley, a longtime employee and unofficial company historian, calls it "the big, flat automatic."

"You've got three machines here and each one has two heads on it, so theoretically we could be making six different items at a time," he says. Conley says that's 3,000 dozen pieces — or 36,000 pieces of pottery — every 8-hour shift. (People who make dishes talk in dozens.)

There have been improvements. Computers control the firing now. 3-D printers speed the design process. Ceramic engineers found a way to make glaze shiny without using lead — all in house.

"The people that owned our company have always put profits back into the plant to modernize, and we've always had state of the art equipment [like the big, flat automatic], and I call that state of the art even though that's as old as it is, it's almost 60 years old," Conley says.

Fiesta Revival

Inside the old buildings, with fog pouring off the Ohio River and drifting into the windows, the ware comes out of the fire, magically transformed — creamy orange, intense red, vivid turquoise. Bright pottery, stacked in bins and crates, are piled all over the place.

"I remember the first time I actually went to the facility and I'm looking around and I'm thinking, 'Boy am I back in the 1940s or what?' I mean, even the office it isn't all spruced up," says Bruce Smith, the head of the union representing the pottery workers. "It's the old look, and they're focused on making product and not being flashy." He says while nothing about Homer Laughlin is flashy, the workers do make decent money.

"They're good jobs and they're making a living, being able to buy a home and raise a family and retire with some dignity," Smith says.

Both management and labor consider that an achievement.

"I'm very proud to have kept this business here in the Ohio Valley. That's very important to us," says Elizabeth Wells McIlvain, the first woman to lead Homer Laughlin, and the fourth generation of her family at the plant. Her immediate family now owns most of the business. Her daughter, Maggie, is an intern in the marketing department.

Homer Laughlin stopped producing Fiesta for a time beginning in 1973. A harvest gold color and an avocado green didn't sell. But in 1986, Bloomingdale's came calling looking for a retro china for its stores, and Homer Laughlin made a typical, practical decision: restart an old line and revive Fiesta for retail sale, along with its existing hotel and restaurant business.

"We have two sides of the business and that's helped us tremendously because it seems when ... the retail side of the business is flourishing, the hotel side is ... having difficulties, and vice versa," McIlvain says.

It helps that Fiesta has a big fanbase. Collectors stand in line for hours to get into the factory tent sales. Fans meet, they swap, they critique the company's color choices. And they wait for the new Fiesta color unveiled each March. (The color for 2014 is poppy, a bold, saturated orange.)

"They always have suggestions. One year they all wanted fuchsia, and they all arrived to Homer Laughlin to go on their tours dressed in whatever fuchsia they had. That was their silent but very loud statement," McIlvain says.

But she offered no color clues for this coming March. "That's a very deep, dark secret," she says with a laugh.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.