More than 9,000 former felons have registered to vote in Virginia since April, when the governor issued an executive order restoring voting rights to more than 200,000 ex-offenders. Democrat Terry McAuliffe said the residents, who are no longer in prison, had paid their debt to society.

But Republicans are suing the governor. They say McAuliffe overstepped his authority and that trying to restore rights to so many people all at once has led to mistakes. The state Supreme Court is scheduled to hear the case July 19.

In the meantime, voting rights groups are trying to register ex-offenders as quickly as they can. Matt Rogers, an organizer with the progressive group New Virginia Majority had luck recently when he randomly stopped people in the streets of Arlington, Virginia to see if they were registered to vote. The first person he asked was Roger Coles, who has a felony record and was eager to sign up.

"I voted once before I got into trouble," said Coles, explaining that was back in 1997. He welcomed the governor's order, and said the old process — which required former felons to individually petition to have their rights restored — was too complicated for him.

"It means you count," added Anthony Puryear, who was walking nearby. Puryear said he was released from prison a month ago and plans to register as soon as he's off parole. He said voting is important for people like him who are trying to get back on their feet and stay out of trouble.

"It doesn't do anybody any good to try to disenfranchise anybody and make it harder for them to reintegrate themselves into society. A lot of them need every freedom they can get," he said.

Appearing last week in Alexandria, McAuliffe said that's one reason he issued the order. He noted that the building he was in, Freedom House, was once the site of the largest slave trading company in the United States. McAuliffe said that when ex-felons lost their voting rights in Virginia back in 1902, African-Americans were hit the hardest, because they've been incarcerated at a higher rate than whites.

"So I was glad that 114 years later, I got to erase a lot of racial prejudice in the Commonwealth of Virginia," he said, adding that he was doing what most other states have already done. Only Iowa, Kentucky and Florida still ban ex-felons from voting.

But Republican lawmakers in Virginia say McAuliffe's blanket order violates the state constitution, and that he only has the power to restore voting rights on a case-by-case basis.

"The reason would be when you do it all at once, and don't look at them one by one, you aren't taking into consideration how violent the offense might be, whether it's a repeat offender, whether they paid restitution to their victims or medical bills and things like that," said Rob Bell, a Republican member of the House of Delegates. "And it's not just the right to vote, which has gotten the most attention, but it's the right to sit on juries."

Republicans complain that McAuliffe's list of ex-offenders eligible to have their rights restored has been a mess. It has included the names of some violent criminals who are still in prison.

"He again took the absolute most conscienceless murderer and treated him exactly like a shoplifter. And then he couldn't be bothered to get his list right," said Bell.

The governor's aides admit there have been some errors on the list, but say they've been fixed. They also note it's still a crime for anyone in prison or on supervised probation or parole to cast a ballot.

Republicans suspect the real motive for McAuliffe's order is political. The governor is a close ally of Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, who could benefit from more African-American voters if the race in Virginia is tight. McAuliffe denied that was his reason for issuing the order.

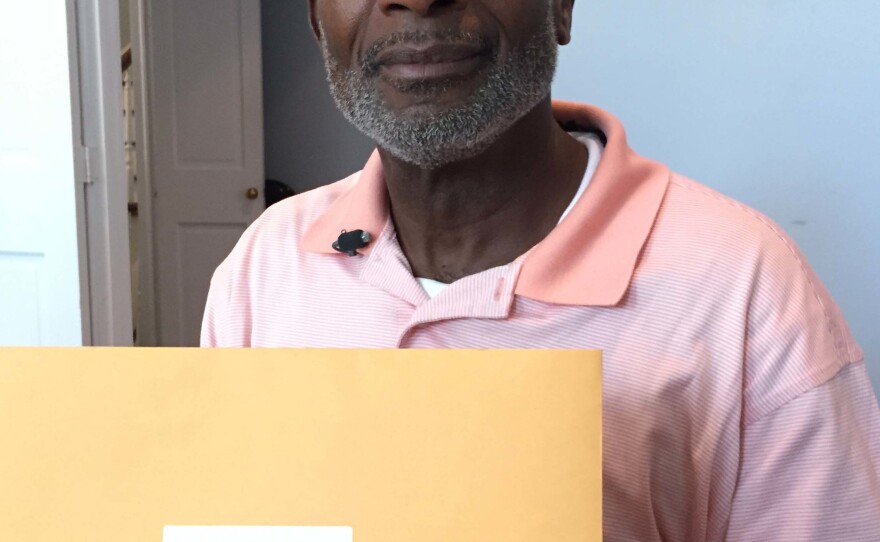

The governor ended his visit to Freedom House by handing a copy of his executive order to Robert McNeil, who's been out of prison since 2008 after a string of felonies. McNeil, who is 62 years old, says he'll vote for the first time in his life in November.

"Thank you, thank you," he told the governor, with tears in his eyes.

McAuliffe assured McNeil that the voting rights are permanent. The governor said even if he loses in court, he'll sit down and sign all 200,000-plus restoration orders one at a time.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.