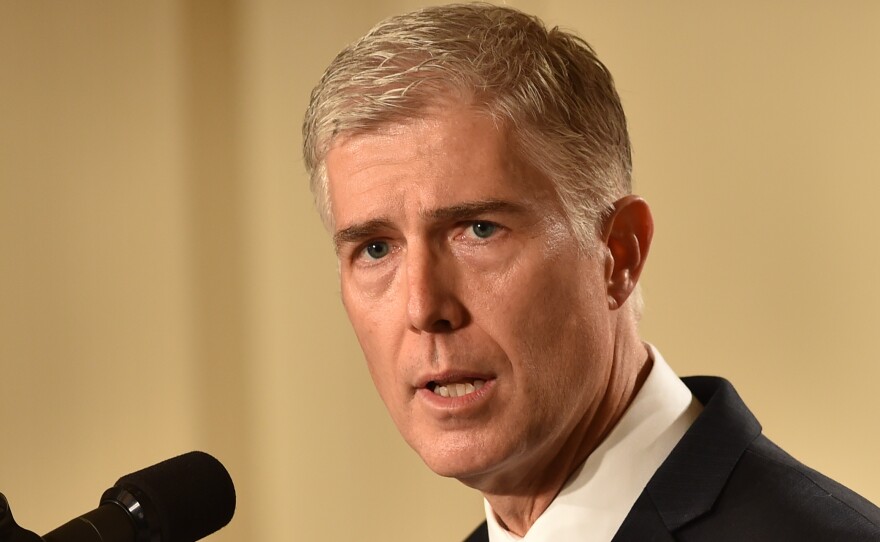

With the Senate Judiciary Committee set to open hearings on the nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch to the U.S. Supreme Court, the game of confirmation cat and mouse is about to begin. Senators will try to get a fix on Gorsuch's legal views — and the nominee will try to say as little as possible.

Supreme Court scholars and practitioners on the right and left may disagree about whether they want to see Gorsuch confirmed, but in general there is little doubt about the nominee's conservatism. Indeed, his conservative pedigree is the reason he was picked.

"On issues like abortion and affirmative action and gun rights and states' rights, we can expect him overall to be a reliable conservative vote and someone who is going to forcibly and eloquently put forward conservative positions on the court," predicts Richard Hasen, professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine.

Not that Gorsuch has ruled on all these issues. He has not. But the legal road signs are there.

Gorsuch, for instance, has never ruled directly on an abortion question, but he has ruled on questions involving contraception and public funding for Planned Parenthood — unrelated to abortion. And in none of these cases has he sided with advocates of birth control or abortion rights.

Setting the Supreme Court up for Hobby Lobby ruling

One of his most controversial opinions involved Hobby Lobby, a chain of craft stores that employs 13,000 full-time employees, most of them women. The company challenged the federal law requiring for-profit corporations to provide health insurance plans that cover birth control.

Gorsuch and a majority of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the corporation had a religious right not to provide birth control coverage. A sharply divided U.S. Supreme Court would later agree, ruling for the first time that certain for-profit corporations have protected religious rights.

What makes this case particularly interesting is a concurring opinion that Gorsuch wrote about the corporate owners' rights.

"All of us face the problem of complicity," he wrote. "All must answer ... to what degree we are willing to be involved in the wrongdoing of others." Here, he noted, the owners believe that for their company providing insurance that includes coverage for birth control drugs or devices "violates their faith."

In many ways, he continued, "this case is a tale of two statutes." One, the Affordable Care Act, compels the owners to provide such inclusive health coverage. The other, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, "says they need not." And the "tie-breaker," Gorsuch said, is the religious protection law because it is a "super-statute" that trumps others, except in special circumstances.

Debate over extent of religious freedom

Gorsuch critics disagree with his assessment.

"To what extent do people with religious beliefs have to follow the law if they believe it violates their conscience? What is the outer limit of that?" asks Caroline Fredrickson of the liberal American Constitution Society. "I think that's a potentially very frightening direction for the law to go."

What if, for example, a hotel or restaurant owner has a religious belief that bars serving African-Americans or non-Christians or gay people?

Indeed, there are a variety of such legal clashes working their way up to the Supreme Court right now. One case pending before the court tests whether a bakery can refuse to make a cake for a same-sex wedding.

Melissa Hart, director of University of Colorado's Byron R. White Center for the Study of American Constitutional Law, knows and respects Gorsuch, who also teaches the school in Boulder. Still, she understands the wariness about his views on religious freedom.

"I think it's reasonable for people to look at Hobby Lobby and, for those who support marriage equality, to be concerned," she says.

But Mark Rienzi of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty says that the Hobby Lobby decision is in line with the religious freedom law that Congress passed by overwhelming margins in 1993.

"It says that the baseline rule in America will be that we respect religious diversity and, for the most part, we're not going to force people to violate their religious beliefs unless we have a really good reason to," Rienzi explains.

In other words, those like Rienzi believe that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and the religious beliefs it protects supersedes the rights of employees to have comprehensive health insurance, even though for most women of child-bearing age, contraception is a substantial regular health expense.

More confirmation fodder

Other Gorsuch decisions relating to religion will undoubtedly come up in next week's confirmation hearings. Among them, a vigorous dissenting opinion Gorsuch gave concerning a series of 12-foot crosses along the roadside on public land. The Utah Highway Patrol Association wanted to erect the crosses to memorialize fallen troopers.

Gorsuch's colleagues on the 10th Circuit ruled against the crosses because a reasonable observer would take them as a sign of a state endorsement of Christianity. The Supreme Court declined review, leaving in place the decision that forbids the crosses.

Although Gorsuch has not written directly about abortion, he did write a book called The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, in which he writes that "human life is fundamentally and inherently valuable" and "the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong." But he describes the court's decisions on abortion in a straightforward way, without adding almost anything in the way of a personal opinion.

The book, academic in tone but lucid in presentation, concludes that there is no necessary connection between the right to abortion and a right to assisted suicide. It does, however, quite clearly subscribe to the notion, adopted in most state laws, that individuals have the right to hasten their own deaths by refusing nutrition, water or medical treatment.

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.