When she's trying decide which art supplies to buy for her class, Tennessee art teacher Cassie Stephens hops on Instagram. She'll post the question on her Instagram story, and within minutes, other art teachers will send her ideas and videos.

Teachers like Stephens have formed something of a community on the app. Using hashtags like #teachersofinstagram, teacher Instagrammers post photos of meticulously crafted classroom decorations, lessons and even their daily outfits (Stephens posted a picture of her pencil-shaped scarf).

"Instagram is just a way for me to constantly take a peek into another art teacher's room," Stephens says.

She has about 76,000 followers, which is not uncommon for some of the more popular teacher Instagram accounts.

Teacher Instagrammers say the accounts help them connect with each other, which can be especially helpful for teachers who are the only person teaching their subject or grade level at their school. It can also be a way to bring in extra cash, with some using their account to promote a company's products or sell their own resources.

"I feel like I have this community of teachers that kinda get me, whereas before it's always been a lonely island syndrome, when it comes especially to teaching art," Stephens says. "And now I don't feel that."

Turning Insta-worthy lessons into cash

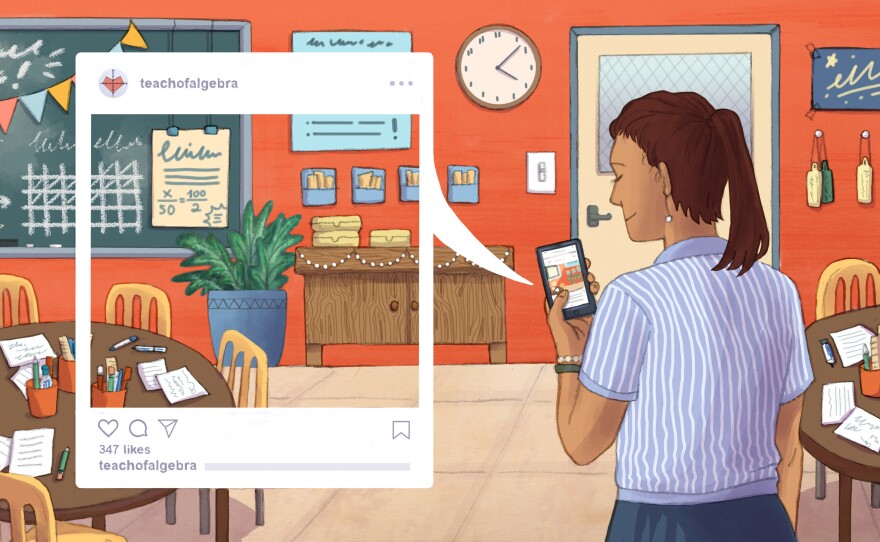

When the bell rings for math teacher Rory Yakubov's free period, she says she whips out her phone.

She snaps a photo of the activities she used in class that day, like a colorful chart she made about absolute value equations. She saves pictures of her classroom decorations, like her picture-perfect chalkboard, to post at night when more people are using the app. Sometimes, she updates her Instagram story with a video of herself explaining a lesson plan.

It's all an effort to draw other teachers to her Instagram account.Yakubov started her account in 2016, mainly to showcase her classroom and connect with other instructors. Now, it's also a tool to promote her lesson materials, which she sells on Teachers Pay Teachers, an online marketplace for classroom resources. She says she mostly creates those materials during the summer.

Her online store has helped her double her teaching salary this year. The extra cash means she can afford to sign her kids, ages 3 and 6, up for after school activities. Not all her posts promote her Teachers Pay Teachers account, she says, but many do.

"I'm able to generate this extra income because people really like what I'm creating, which makes me so beyond excited and happy, but also now I have a financial benefit," Yakubov says.

For Stephens, her account's success has lead to speaking engagements and to her writing a book. It's not a reason to quit her teaching job, she says, but it's added extra income to her wallet. At the same time, it's increased her workload.

"It's difficult at times," Stephens says. "I try really hard to ... just take everything in stride and just try to tackle one thing as it comes at me as opposed to just thinking of everything I need to do and feeling extremely overwhelmed."

Sharing ideas with each other

Not only are teachers making extra cash through Instagram, they're also using it to swap ideas for their classrooms.

On Halloween, English teacher Emily Aierstok transformed her New York classroom into an escape room. She draped caution tape across the tables and tacked pictures of poet Edgar Allan Poe on the walls.

Thanks to photos posted on her Instagram account, a teacher in California replicated the lesson that same day, she says. Andrew Frey, an elementary school teacher and Instagrammer in Illinois, implemented guided meditation and conscious yoga into his classroom after he saw it on Instagram. He learned more by sending a direct message to a teacher, who connected him with videos, websites and ideas to teach guided meditation to fourth graders.

"Any teacher that you see on Instagram or any type of social media account, they'd be lying if they said that their ideas weren't an inspiration from somebody else," Frey says.

There's also an "invisible component" of the community, Frey says: direct messages. One example: teachers will send him direct messages about his classroom decorations, and he'll reply with his own ideas or suggestions he's received from others, he says.

Direct messages are also a way teachers spread the word about in-person meetups. In New Jersey, teacher Instagrammers met at a restaurant over the summer to share ideas, Yakubov says. In California, hundreds of teachers will spend a weekend together in February, says Tyler Richards, a sixth grade instructor in California.

One downside to teacher Instagram: the comparison game. Heidi Rose, a first grade teacher in Colorado, runs an account about minimizing waste in the classroom. She says Instagram has been a great tool to find ideas, but it's also made her compare herself to other instructors more so than she did in the first six years of her career.

"It's kind of a double-edged sword," Rose says.

It can also be tricky when teachers post photos of their students, says Girard Kelly of Common Sense Media, a group that studies how media and technology affects kids. Educational institutions are required by law to notify parents annually of their rights regarding their student's education records, Kelly says.

Schools typically use that form to get permission to add a student's information to educational technology, like Google Classroom or Edmodo. But, the form may not cover a teacher's personal Instagram account, Kelly says.

Teachers should send a separate form to parents with information that they'll be posting pictures of students online, Kelly says.

On Stephens' account, she doesn't post photos of her students. Instead, she posts photos of her teaching outfits or videos of lessons, like one when she teaches kindergarteners how to use scissors and glue (spoiler alert: it includes a lot of different voices).

"Often times, I'll share the awesome things we're doing," Stephens says. "But I also like to show what I call the hot flamin' dumpster fire that is my room. That is the constant state of working with kids and creating."

Copyright 2018 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.