In the summer of 2014, a swarm of police arrested Aaron Harvey near where he was living outside Las Vegas. Harvey is from San Diego, and was charged as a test case by San Diego District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis using a law that had never been used before.

It said someone could be charged for conspiracy for gang shootings, even if that person had nothing to do with the shootings at all. That was the case for Harvey. He was charged because he was in social media pictures wearing gang colors and making gang signs.

A judge dismissed the charges against him, but not before he spent seven months in jail.

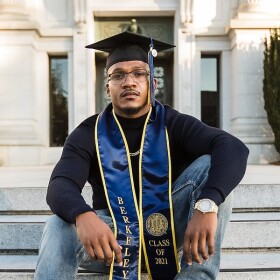

Now, Harvey has done something that when he was in jail seemed like an impossible dream: graduating from UC Berkeley.

“I remember sitting in jail and a Berkeley commercial came on and I remember telling my cellie on the same case, I was like, ‘if they ever let us out of here, I'm going to Berkeley,’” Harvey recalled. “Everybody goes ahhh, you sound stupid.”

Harvey shared that memory in November 2018, during his Thanksgiving break from his first semester at UC Berkeley. He talked about the huge challenge ahead of him: graduating from one of California’s best universities.

“Sometimes I feel like if I don't graduate from this school, I can never come back to San Diego because it's just a lot of pressure,” he said. “I got a B on my midterm and flipped out. I've never gotten a B on anything. So that was very humbling. But then at the same time, I was thinking, this is going to mess up my GPA, because I have to have a high GPA because I have to go to Harvard for law school. But I'm putting all this pressure on myself. It's like, chill out. It's a midterm. It's a B, relax.”

Khalid Alexander, a community leader who’s known Harvey for a long time, said his case made the expectations that much higher for a true redemption story for both Harvey and rapper Brandon Duncan, who was charged in the same case.

“There was a huge amount of community outpouring while they were actually in jail,” Alexander said. “Once released, instead of the two of them disappearing into obscurity and just being thankful enough to have been released, they ended up dedicating a large amount of their time to not only be active in the community, but to be active voices calling for reform of the system or for addressing some of the wrongs that have happened.”

Harvey would have been just as happy, if not happier, without all of the attention, Alexander said.

“I think it's unfair any time a community puts their hopes on any one individual, I think it's an enormous amount of pressure and responsibility that you didn't necessarily ask for,” he said.

Harvey said the case, and the judge’s decision to overturn it, along with a $1.5 million settlement he and Duncan received from the city of San Diego, brought a lot of change. It led to Dumanis promising she would never use Penal Code 182.5—the law she charged Harvey under — again.

RELATED: Tiny Doo, Aaron Harvey React To Their $1.5M Settlement After Wrongful Arrest

Dumanis did not respond to requests from KPBS for this story. In 2017, she told The San Diego Union-Tribune, “when we think we are doing something positive, like filing this case to get the people who are murdering innocent people, people within the African American community, I have done something inadvertently that (some people) view as wrong.”

But, Harvey said, he feels the good things came “at the expense of my life.”

“Yes, great, we got all these things, but it kind of ruined my life as well,” he said.

Again during his Thanksgiving break in 2018, during his first year at Berkeley, Harvey reflected on how, in some ways, it was difficult for him to be around his old neighborhood because he felt everyone he was was putting pressure on him.

“They’re like, when are you going to start law school? And I'm like, I'm only halfway there my first year,” he said. “I don't think I've ever said this before, but, of course, I care about social justice and I've pretty much dedicated my whole life to it. But to be honest, I'm doing all of this because there was a guy on our case, his name is Justin Anderson, he's doing life on our case. And he's like I was like he's like my brother, you know? We grew up six houses down the street from each other. And I am becoming an attorney to get him out of jail. I'm going to get him out of jail. And then after I do that, I might not want to study law anymore.”

Harvey talked again during his winter break in 2018, and it seemed like his college experience was taking a huge mental toll. He looked tired, thin, and you could hear the exhaustion in his voice.

“Four or five weeks ago, I'm ready to drop out,” he said. “I don't feel like it was tough academically, but there's a language that you have to decode. You have to demystify a lot of things (at Berkeley) that I wasn't necessarily aware of going up there. I'm just thinking, you go to class, read, study, turn in your paper. But building relationships with professors, being in relationships with the grad students who actually grade your papers, not the professors. Nobody told me this. Why am I still going to talk to this professor and he knows nothing about my work. It sounds so simple, but this is very complex for a person who doesn't know.”

“Going to jail is easy, I could physically do that,” he added. “But you asked me to go talk to a professor during office hours and I'm about to have a panic attack.”

RELATED: Lawsuit Doesn’t Allay San Diego Rapper’s Fears Of Arrest

Alexander, the community leader, said when Harvey went to Berkeley, he became a representative of the larger community in Southeast San Diego, a predominantly Black and Latinx and lower-income part of the city.

“His success was tied up in what people I think felt was their own success,” Alexander said. “And similarly, his failure I think was connected and tied up in what the larger community would see as their own failure.”

“He also, as an individual, I think can represent kind of what it's like to be Black in this country, what it's like to be an African-American in this country where you do have to work harder,” Alexander added. “If you do mess up, there's going to be more attention.”

“I always feel like I'm being almost interviewed every time I see somebody, like you want to present yourself as, ‘I've been doing really well,’” Harvey said. “I can't give them how I really feel about being up there.”

Harvey remembers people who left his neighborhood before, went to college or law school, and when they came back, they talked differently and dressed differently. He resolved not to do that.

“They call it code switching, so people could feel like, ‘he's still the same person, he's just doing other things, it motivates them,” he said.

But, at Berkeley, Harvey said a professor told him to speak differently, to “use more academic language.”

“And I challenged her, who set the standard for what's academic language?” he said. “So you want me to speak white? What does that even mean? Define that. Who set the standard for what is the correct way of speaking?”

At the end of his first year at Berkeley, Harvey sounded much more confident in his abilities and was already thinking about what he’d do when he graduated. He was majoring in political science and wanted to go to law school at an Ivy League school, but was also still thinking about his mental health. Because Harvey was arrested suddenly in a police raid and spent time in jail for gang crimes he had nothing to do with, he has traumatic memories.

“I'm super paranoid, I’m always like, who is that, why is that person looking over here? I’m always thinking somebody is a police or taking pictures,” he said. “In my second semester, I almost feel like I put myself in position for these kinds of episodes to happen because of what I'm choosing to study, and then I'm at Berkeley, which is home of everything political.”

RELATED: New Voices: A Younger Generation’s Urgent Quest For Change In Southeast San Diego

Two years and one pandemic later, Harvey graduated. He came back to San Diego for a visit, and earlier this month sat at a picnic table by Chollas Lake to reflect on everything that had happened. For one, his plans have changed.

“I think I figured out law school wasn't for me my first year at Cal, because the more and more I started digging into the law, working with attorneys, dealing with cases and things like that, they're still finding ways to just incarcerate people,” he said. “I feel like being an attorney boxes you in. I'm dealing with the law, and if the laws are immoral, then it doesn't matter.”

Now he wants to work in real estate, and do development jobs where he would hire people with felony records.

“What can I provide poor people to kind of minimize the risk they're willing to take that's going to put them in prison?” he said. “I'm going to disappoint a lot of people. People are like, what are you going to do? I'm like, I don't know, maybe I just want to go to sleep. It’s been a long seven years and I'm exhausted. I'm tired, but I'm excited too, because now I feel like I can do what I want to do. I feel like I can be more impactful outside the law. With my circle, we have these conversations and they are just like, ‘man, do what makes you happy.’ And I stick with that.”

But Harvey is not really just lying around. He’s working with the Berkeley Underground Scholars helping people who’ve been to prison write college essays and do their applications.

Harvey listened to a few of his old recordings he made in 2018, about applying to only Ivy League law schools, about having a panic attack over the B on his midterm, and he laughed.

“Yes, I feel none of that anymore,” he said. “I think it's just, well, one therapy, right? Man, a whole lot of that, right? I see pictures of myself like three, four, or five years ago and I'm like, you look sick, bags under your eyes and am I super skinny. And I just remember, that was when you just really weren't sleeping or you weren't eating and every strange face you thought was a detective.”

RELATED: Police Reform In San Diego A Year After George Floyd’s Death

Plus, he felt all the community pressure “to be like Moses,” he said.

“And it was just like, you’ll kill yourself, you can't do this, this is not sustainable,” he said. “I just kind of let that go, forcing myself to tell the truth to people of, ‘actually I don't know if I want to do that, or actually no, I'm not going to do that.’”

Councilmember Monica Montgomery Steppe, who has known Harvey for a long time, said while he overcame his ordeal, “we know there is still work to do to create and foster equitable treatment for the BIPOC community by the justice system.”

“I continue to support Aaron's efforts to expose the injustices in the system, and I’m so proud he created his own path to success, defying so many odds,” she said.

Alexander, the community leader, added that sometimes a society uses people like Harvey “to make us feel better about an entire system.”

“And while we should definitely celebrate Aaron's success and certainly be proud of all of the accomplishments that he should make, that shouldn't happen at the expense of us recognizing that people like Aaron are the exceptions who were able to be successful in spite of the system and not because of the system,” Alexander said.

Alexander also said Harvey battles with the expectation that he has to be “more than human.”

“That they needed to try to pretend as if they were these kind of square people who were unfairly labeled as gang members instead of saying, hey, even if you are a gang member, this is absolutely unfair, that nobody should be treated this way, whether or not they're from a gang, whether or not they're from a certain neighborhood, whether or not they fit into this nice, pretty box of what we expect a Black man, a young man in this country to to be,” he said. “Is it really the point? The point is that they were victims of a system.”

Now, Harvey does seem lighter, less exhausted, less weighed down, and with some of the ease and carefreeness you’d expect a brand new college graduate to have. He has a young daughter and plans to move out of San Diego for a time, but said he’ll eventually be back to buy a house and raise his family here.

“I'm just starting to feel just a lot lighter on my feet, more energy, and now that is really giving me the clarity on how or what I'm going to do,” he said. “I know it was guilt and everything else, I was trying to take care of everything else and I wasn't taking care of myself. And now I'm like, now I got to take care of myself.”