The whiteboard in Kellie McKenzie’s office shows the choices some of her middle school students have when they’ve misbehaved: Campus beautification, after-school detention, reflection lunch.

The options on the whiteboard reflect a shift in how teachers and administrators are trying to address disruptive student behavior at a school that expels and suspends students at twice the state average for middle schools.

“(The job) is probably 99 percent counseling and 1 percent disciplining,” said McKenzie, the dean of students at Monroe Clark Middle School in City Heights.

The idea she promotes is that students will better learn from their mistakes if teachers and counselors take the time to handle small problems before they turn into big ones.

“Basically, the philosophy is it’s not the severity of the consequence but the assurance that it will be consistent,” she said. “It’s more of a teachable moment, rather than making the kids feel shame.”

Although expulsion and suspension rates overall are falling across San Diego County, middle schools are the exception. Their suspension rates are holding steady. Experts say this is no surprise. As children grow into adulthood, challenging authority and breaking the rules are part of the transition.

Many students at Clark Middle School — 99 percent of whom qualify for free or reduced price meals — face added challenges of poverty, language barriers, incarcerated parents or relocation from war-ravaged countries.

“When you add those issues on top of normal developmental behaviors, of course you’re going to expect more acting out,” McKenzie said.

The staff at Clark has faced its own challenges. It has been cut by 20 percent in the past five years, and 14 teachers — another 20 percent of the staff — received layoff notices recently.

The middle school suspension rate at Clark — about 40 suspensions per 100 students — is about double the average for traditional middle schools in San Diego County. But then middle schools in general in California suspend at a much higher rate than high schools.

“Middle schoolers have a lot of transition they’re going through at that time,” said Loretta Middleton, Executive Director of Student Support Services for the San Diego County Office of Education.

“They don’t know how to manage their changing lives.”

While suspension rates at middle schools in the county remain steady, expulsion rates have dropped at these schools, including Clark, over the past five years.

McKenzie attributes that in part to a strategy called Positive Behavioral Supports and Interventions, which works to standardize the types of behaviors for which students are disciplined as well as a teacher’s response to those behaviors. One of the end results, she said, is giving students many chances to change their behaviors. It makes expulsion a last resort.

Russ Skiba, a professor in Counseling and Educational Psychology at Indiana University, said positive discipline strategies can be effective, in large part, because they establish a consistency in the way teachers interact with students.

The results of implementing the new discipline strategy have been telling, McKenzie said. The number of students referred to her office for misconduct fell by half from 2010 to 2011.

When teachers handle more problems in their own classrooms rather than sending students to the office to be disciplined, the students don’t miss out on instruction. And, the fewer suspensions and expulsions a school hands down, the fewer school-aged kids are left home alone or wandering the streets.

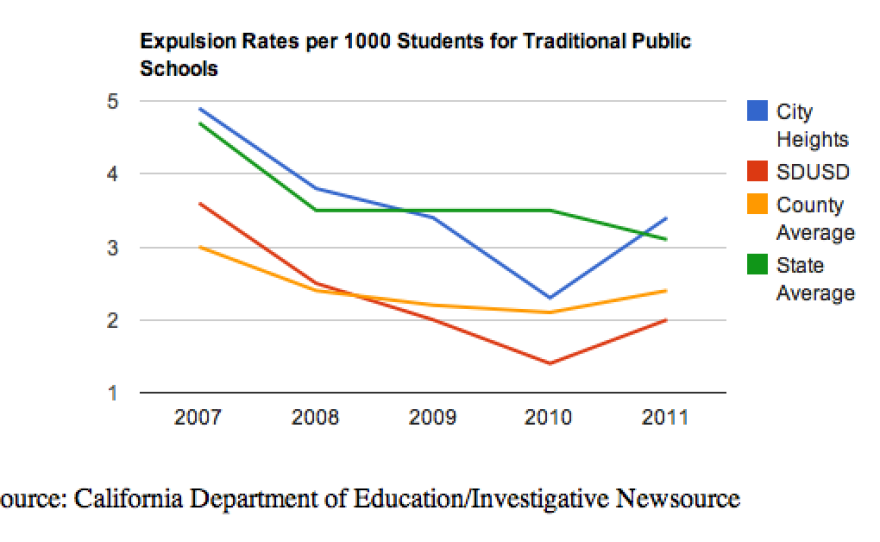

Statewide, expulsion rates at traditional public schools fell by a third during the past five years. In San Diego County, they fell by about 20 percent.

“We’re headed on the right path,” Middleton said, largely by searching for other means of intervention and support for students rather than simply expelling them.

McKenzie said the school environment at Clark has improved significantly in the past few years. The students feel more comfortable talking to the teachers about problems in and outside of school. And while the suspension rate might be up, so are test scores. Last year, students met their annual improvement goal.

“I know the kids feel safe at this school,” she said. “I think we’re making progress.”