Before dawn Thursday, police demolished a pro-Palestinian encampment at UCLA — using flash bangs, firing projectiles at protesters and arresting those who refused to leave. It was in stark contrast to the scene overnight Tuesday, when counterprotesters had torn at barricades, thrown fireworks, and beat and pepper sprayed the protesters — and no law enforcement officers intervened or made any arrests.

The reason for such a mixed response from law enforcement: haphazard adherence to UC President Michael Drake’s 2021 UC Campus Safety Plan.

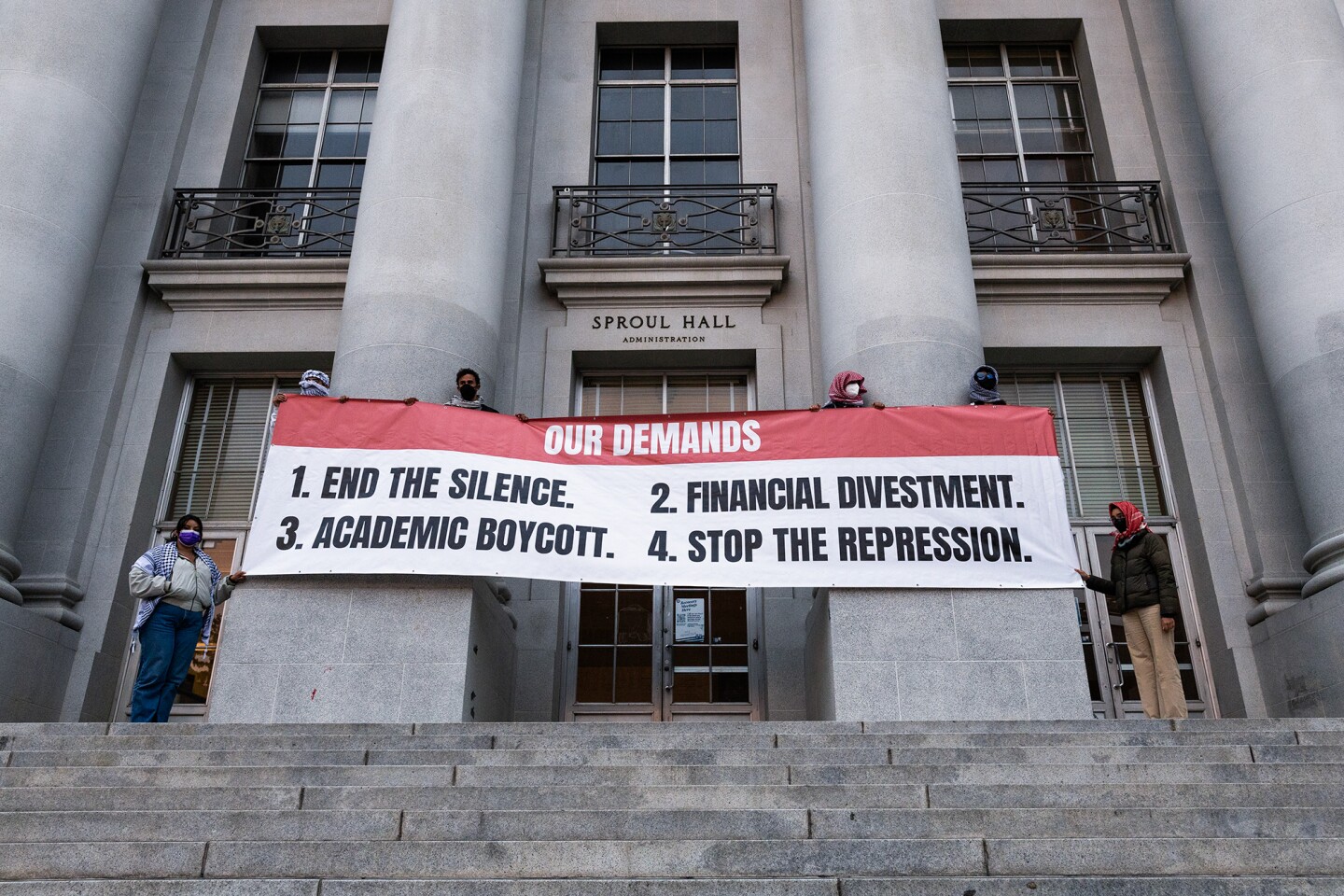

Encampments at a growing number of universities across the state and nation are sparking battles between students’ free speech and campus policies against trespassing and obstructing operations. For the University of California system, the encampments at five campuses have been a test of newly implemented campus policing reforms meant to address systemic racism post-2020.

Drake’s safety plan states: “The University will reinforce existing guidelines that minimize police presence at protests, follow de-escalation methods in the event of violence and seek non-urgent mutual aid first from UC campuses before calling outside law enforcement agencies.”

The plan was designed to deter potential violence — and reduce a police role in campus protests. But now, people are questioning why law enforcement did not break up any of the physical assaults or otherwise intervene as violence escalated at the Los Angeles campus on Tuesday. According to a statement Drake released yesterday, there were at least 15 injuries and one hospitalization.

And now some are questioning the university’s decision to forcibly dismantle the protesters’ encampment this morning when they had been peaceful.

The UC president has ordered a review of UCLA’s “mutual aid response” and UCLA Chancellor Gene Block had promised to “dismantle (the encampment) at the appropriate time.”

“My office has requested a detailed accounting from the campus about what transpired in the early morning hours today,” Drake said yesterday. “But some confusion remains. Therefore, we are also ordering an independent external review of both UCLA’s planning and actions, and the effectiveness of the mutual aid response.”

UC lecturers were quick to call for Block’s resignation on Wednesday, citing the mismanagement of police and security response to the overnight violence. He had already planned to step down July 31.

“Chancellor Block has refused to meet with protesters to discuss their interests; instead he has created an environment that has escalated tensions and failed to take meaningful action to prevent the violence that occurred last night,” the UC lecturers’ statement read.

Counterprotesters had set off fireworks around 10:30 p.m. Tuesday, and later, armed with pepper and bear spray, physically attacked those residing in the pro-Palestinian encampment. During this time, university-hired, unarmed security guards and campus public safety aides watched the scene but did not stop the attacks. By about 1:30 a.m., Los Angeles Police and the California Highway Patrol arrived, after the chancellor called them to assist security guards and UC police. The officers did not break up the violence. Instead, they advanced a line every few minutes to push the counterprotesters out of the area. Some of the counterprotesters who remained, however, continued their assaults.

At about 4 a.m. Wednesday, a small group of student journalists for the Daily Bruin, including Christopher Buchanan, a student fellow for the CalMatters College Journalism Network, were confronted by a group of counterprotesters who began berating them. They targeted the staff’s news editor, calling her names, and blocked the journalists’ route to the Daily Bruin office. One shined a strobe light into Buchanan’s face while others attacked him as he fell to the ground.

“After I was struck and debilitated, I was surrounded by four to seven counterprotesters who proceeded to punch and kick my head and torso for thirty seconds to a minute,” Buchanan said. “I didn’t sustain any internal injuries, but I was badly bruised on the body and face.”

Buchanan said this all happened within earshot of CHP officials, who did nothing to intervene.

Students and government officials decried UCLA’s response to the counterprotesters’ attack. UCLA refused to provide interviews or answer questions about their policing response.

California Assemblymember Rick Chavez Zbur, a Democrat whose district includes UCLA, issued a statement condemning the violence against pro-Palestinian protesters.

“The horrific acts of violence against UCLA students and demonstrators that occurred on campus last night are abhorrent and have no place in Los Angeles or in our democracy,” Zbur said Wednesday. “No matter how strongly one may disagree with or be offended by the anti-Israel demonstrators’ messages, tactics, or goals, violence is never acceptable and those responsible must be held accountable.”

In the past few days, UC Irvine and UCLA declared their campus encampment protests illegal and in violation of the state education code against non-UC use of university property. Many pro-Palestinian student advocates see this position as an attempt to disrupt their advocacy.

In responding to the encampments, the UC, unlike some universities, had avoided an aggressive law enforcement response. The UC Campus Safety plan, however, has not been uniformly followed at each campus.

UC Irvine appeared to ignore the campus safety plan. When an encampment was erected on April 29, the university immediately called in the UC police department, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department, and the police forces of Irvine, Costa Mesa and Newport. Officers in riot gear barricaded the encampment entrance.

UC Irvine spokesperson Tom Vasich described the decision to involve five law enforcement departments as “a standard response” for situations where the campus needs support while simultaneously describing the protest as a “very peaceful environment.” He attributed the police response to potential trespassing violations from people not affiliated with the university.

“This isn’t a free speech issue, this is a trespassing issue,” Vasich said.

Sara, a UC Irvine student studying psychological sciences who only gave her first name in fear of retaliation for participating in the protest, said that at around 9 a.m. on Monday, law enforcement prevented students from entering the encampment and giving protesters water.

Despite police pushback, she said students and bystanders later created barricades around their encampment, allowing students to enter the area and receive supplies. “The students here all know the risks,” Sara said. “But regardless, they stood their ground and will continue to stand their ground until our demands are met.”

UC Irvine Chancellor Howard Gillman said in a Monday night statement “we support the right of our community to protest” but their hope is that protestors “do not insist on staying in a space that violates the law.” Gillman promised to work with students to find a different location “that is appropriate and non-disruptive.”

How the UC plan is supposed to ensure safety

The UC Campus Safety Plan is being put to the test amid heightened tensions between pro-Palestinian groups calling for a ceasefire in Gaza and for the UC to financially divest from companies with ties to Israel and pro-Israel groups counterprotesting and calling the actions of those in the encampments anti-semitic.

The UC Office of the President released a statement on April 26 rejecting demands for divestment.

“The University of California has consistently opposed calls for boycotts against and divestment from Israel,” the statement said. “While the University affirms the right of our community members to express diverse viewpoints, a boycott of this sort impinges on the academic freedom of our students and faculty and the unfettered exchange of ideas on our campuses.”

President Drake’s office refused multiple requests from CalMatters to answer questions about UC’s response to campus encampment protests.

The UC’s policing reforms came after the system faced several high-profile instances of excessive force in response to student advocacy on campuses. In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street protests at UC Davis drew international attention when peaceful activists were pepper sprayed by the university’s police department. In the end, students won a $1 million settlement from UC Davis.

In 2020, racial justice organizations and Black student unions at the UC’s nine undergraduate campuses led protests over the police-custody murder of George Floyd, and to cast a light on other Black Americans killed by law enforcement officers.

Their activism elevated negative experiences that some students of color reported with campus police. Students and employees demonstrated against racial profiling and a lack of police transparency. Some pushed for reforms; others called for abolishing police on university campuses.

The 2021 safety plan instituted data dashboards, police advisory boards, mental health responders and professional accreditation for individual police departments. According to the UC’s director of community safety Jody Stiger, all 10 campuses are expected to put the plan into action — with the final, delayed step being professional accreditation for campus law enforcement agencies — by the end of this year.

The UC Cops Off Campus Coalition, composed of UC students and faculty, has criticized the safety plan for not acknowledging the structural biases of police forces, and only increasing the scope of policing power.

UC Riverside Black Studies professor and faculty coalition member Dylan Rodríguez described the Campus Safety Plan as largely reactionary. He said it is the UC’s attempt to quell a push for police abolition in the wake of the UC’s own crises and Floyd’s murder.

“It’s a response to a period of time in which there are deep questions, fundamental and abolitionist questions, about whether campuses should have fully armed, militarized and, sometimes, riot-gear equipped and SWAT team-trained police officers on their campuses,” Rodríguez said.

The stated aim of UC’s tiered response is to use several non-sworn responders in calls for emergencies that don’t require police. Relying on alternatives to police allows campuses to respond to students in crisis who require mental health support or intervention. The plan also establishes public safety officers to patrol residence halls on foot, escort students across campus at night, provide security for events and diffuse unsafe behavior.

In an interview with CalMatters before this week’s violence, Stiger praised the increase of unarmed security guards and guidance against a police presence at protests. Police were not called to the scene during recent labor strikes, nor for earlier protests on both sides of the Gaza war.

“In almost a majority of those on every campus, you don’t see any police. You might see maybe one or two that are just in the area, but you don’t see a major police presence,” Stiger said.

Late Tuesday, the university delivered a formal letter to UCLA’s Divest Coalition declaring the encampment an unlawful assembly in violation of campus policy. Chancellor Block put out a statement saying the university removed demonstrators’ barricades blocking entrances to specific buildings, and warned that students could face suspension or expulsion.

Campus police chiefs at UC Berkeley, UCLA and UC Irvine refused several requests for comment from CalMatters.

The UC Student Association — systemwide student representatives — published a statement on April 29 in solidarity with students protesting for “Free Palestine” and condemning the law enforcement response.

“We demand that the UC, at a minimum, allow students to exercise their freedom of speech,” the statement read. “We denounce any use of police force to silence us.”

Sergio Olmos contributed reporting from the scene. Christopher Buchanan, Li Khan and Hugo Rios also contributed to this story. All three are fellows with the College Journalism Network, a collaboration between CalMatters and student journalists from across California. CalMatters higher education coverage is supported by a grant from the College Futures Foundation.