There has been a lot of attention paid to the military surge in Iraq. But less heralded has been the so-called civilian surge that's occurring at the same time — though not on the same level.

The civilians helping in Iraq number in the hundreds — not the tens of thousands — and they make up Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs), whose job is to help Iraqi local governments learn to function.

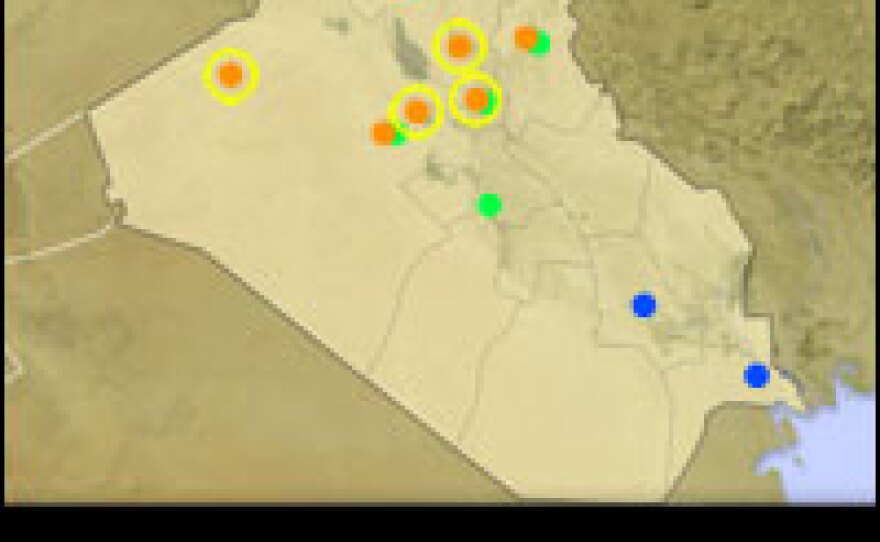

In January, President Bush announced that he was doubling the number of teams from 10 to 20. The U.S. State Department is trying to quickly train people for the task.

John Matel, a foreign service officer, can't quite say what drove him to take an assignment in Iraq. He served in Poland when that country was in transition. He hopes that his experience can translate to Iraq, where he will be running a PRT in Anbar province.

"I've always done local ... I did Krakow in Poland, not Warsaw, at first. I did Porto Allegro in Brazil, not Brasilia," Matel says. "And I come from Wisconsin, which isn't exactly the center of the world ... though we think it was."

Matel has been in the foreign service for 23 years. He doesn't speak Arabic and certainly couldn't learn it in the two-week course that the State Department has developed. Mainly, the course was a chance for Matel to get advice from people who have been to Iraq — such as to wear cotton under the body armor so it doesn't catch on fire.

"That is kind of scary," Matel says. "It never occurred to me to choose my undergarments based on inflammability."

Security is a major theme of the classes, which include first aid and basic weapons training.

Paul Wedderein, also a foreign service officer, describes his class at a raceway in West Virginia, where they are taught how to drive out of danger.

"All I can tell you is that when somebody puts you in a car and says, 'Go hit that other car out of your way,' that's a singularly liberating experience," Wedderein says.

The security training lasts about a week. That leaves just five days for everything else.

Robert Perito, who has studied PRTs for the U.S. Institute of Peace, says that the fact that the officials are getting training at all is an improvement.

"They've made a conscientious attempt to provide the best possible training they can in the five days that are allowed to them," Perito says. "But what the training really turns out to is a series of lectures — an hour or two-hour lecture on Iraq, or an hour or two-hour lecture on Islam, or a description of what PRTs are in an hour and a half. So, there's a lot that gets thrown in very quickly."

Perito has been on panels that were cut short because the people heading out needed more time to get paperwork done. And some foreign service officers have privately complained about the rush to get people to Iraq. Those who are going don't have a chance to learn even basic Arabic, they say.

Ginger Cruz, the deputy special inspector general for Iraq reconstruction, recently testified that the $2 billion-a-year program has been plagued by staffing problems. The new PRTs, which are embedded in U.S. military brigades, have been filled mainly by the military.

"I've spoken to several of these training programs," says Perito, who has seen the military involvement firsthand. "Sometimes you go in there and the room is all uniforms."

The State Department says this is changing. Wedderein says the training course he took was a bit more diverse — and he wouldn't say it was a room full of young people seeking adventure.

"When I looked around that classroom … three of the people at my table were north of 55 and had been doing agricultural all of their lives," he says. "It's not for the adventure, but it is for the mission."

He's hoping that he can do his part to build trust among local Iraqi authorities, helping them work through the bureaucracy and get money for needed projects. Wedderein knows much of his training will be on the job — and that even his assignment could change the moment he lands in Baghdad.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))