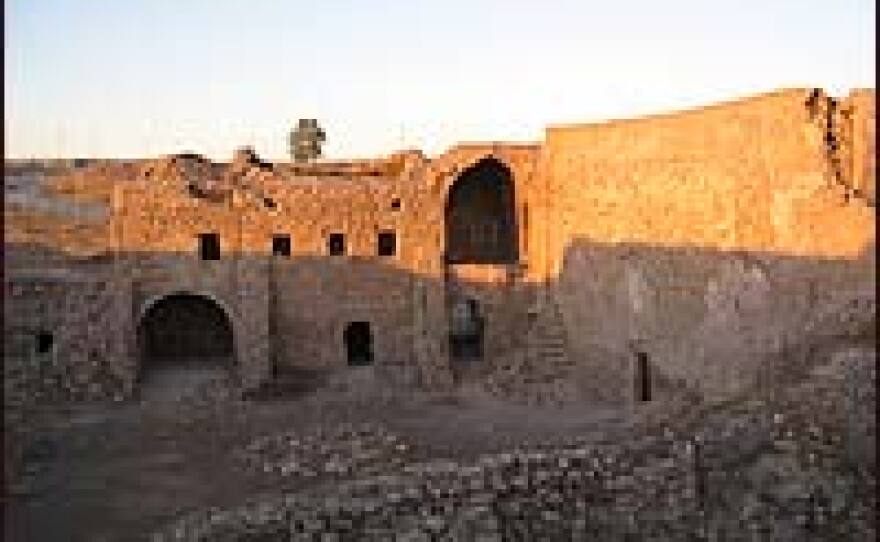

In a patch of sloping hillside in southwest Mosul — next to a junkyard of destroyed Iraqi army tanks — sits Iraq's oldest Christian monastery.

Saint Elijah's, a fortress-like complex of buildings dating to the 6th century, was badly damaged during the U.S.- led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Now, a few U.S. military chaplains are struggling to protect the ancient Chaldean Catholic monastery from neglect, unexploded ordnance and looters.

History of the Monastery

At one time the freshwater creek and surrounding hills, prime grazing land, made this valley a sweet spot for early Christian monks to build a place to live and worship. But today, rusting Russian-made Iraqi tanks and bombed-out car shells are piled in a junk heap next to the monastery.

First Cavalry Division Pvt. 1st Class Nathaniel Irvine walks carefully around shards of old pottery. Chunks of old plates and clay jug handles litter the monastery's ground along with shrapnel from tank and mortar rounds. U.S. soldiers have removed more than 130 pieces of unexploded ordnance from the site, but there could be more.

It's believed Dair Mar Elia, or Saint Elijah's monastery, was built in the late 6th century by early Chaldean/Assyrian Catholic monks. Armies under Persian ruler Tahmaz Nadir Shah attacked and looted the place in the 17th century, slaughtering the three dozen monks who lived here.

By Chaldean/Assyrian tradition, monks' bones were often buried in the monastery walls. And on this windy hillside, Irvine says, soldiers have found what they believe are human remains sticking out of the crumbling walls.

"Look inside down there; there's a bone they've found down there, so it's believed they're probably buried in these two tunnels," he says.

Destruction of Today

Today the outer wall of the monastery's chapel looks as though it were swatted by the hand of a giant. But it was no giant: It was a U.S. anti-tank missile fired in 2003 by advancing 101st Airborne soldiers battling an Iraqi tank unit based in and around the site.

"(The 101st) fired upon the tanks using stuff that would destroy the tanks. They were being fired at so they had to return fire," Irvine says.

The tow missile that crashed into the ancient chapel's wall could be chalked up to the fog of combat. But the same can't be said for the sophomoric graffiti scrawled around the place and the big "Screaming Eagles" logo painted above the chapel's door.

"If you look over the sanctuary you'll see the 101st Airborne patch. We've since tried painting over it and washing it off, and it won't come off," Irvine says.

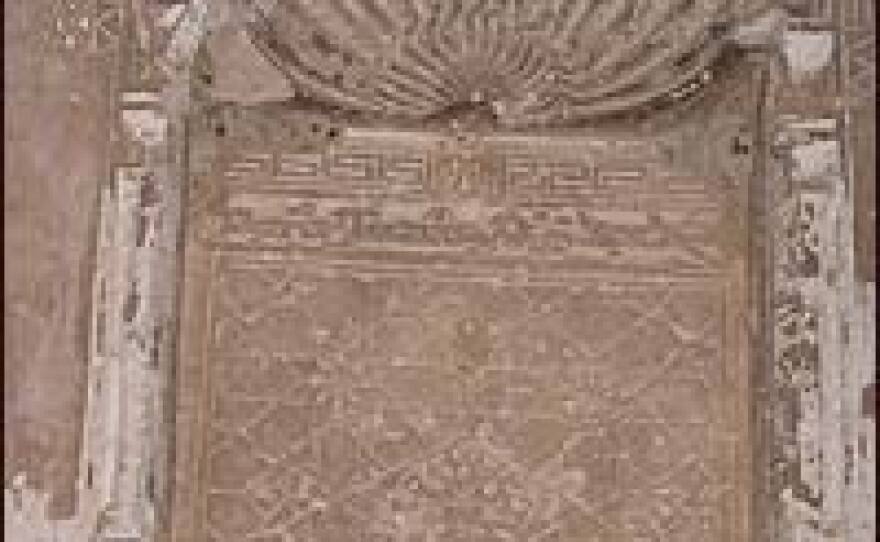

U.S soldiers four years ago also white-washed the stone alter and the two-story high walls of the chapel, covering remnants of 600-year-old murals.

An ornate, shell-shaped stone alcove with a cross still adorns one wall. Looters apparently got the second one: an identically shaped alcove on the other side of the door sits empty with chisel marks around it. And in the roof line, right above the alter, you can still see a square, man-made opening to the sky.

Leaving a Mark

101st Airborne soldiers were hardly the first soldiers to leave their mark here. Previously, Iraqi tank units trashed the monastery, damaging rooms and filing an ancient cistern with trash and feces. Near the monastery's entranceway, there's much older graffiti: A Crusader-era Jerusalem cross is carefully etched into the stone, perhaps a vestige of some medieval battle in the region.

Today the monastery sits on the edge of forward U.S. operating base Marez. Despite the ravages of war and neglect, Saint Elijah's remains an enchanting place. The reddish-brown sand walls seem to soak up the sharp, late-afternoon sun. Underground tunnels, now grass-covered and partially collapsed, poke through the earth near an egg-shaped cistern.

Irvine, a 21-year-old from South Dakota, is trying to help preserve the site and gives soldiers occasional tours.

"I love it coming here," Irvine says. "Just the atmosphere it has versus being at work or running outside the wire where it's stressful. Very relaxing."

Some of the damage U.S. forces did here can't be undone. But U.S. military chaplains are trying to protect the site as best they can during wartime.

Capt. Martin Chang, the chaplain here, calls the largely unexplored site a potential archeological treasure trove. But with a war still on, the simple chain-link fence chaplains have erected around the monastery may be its only protection for years to come.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))