Lana was a teenager when her family made a clandestine journey from Kurdistan to Israel.

It was 1994, and Saddam Hussein had recently lost control of northern Iraq. Rival Kurdish militias were battling each other to fill the power vacuum. In a closely guarded emigration, Lana's family — and a dozen other Kurdish families of Jewish origin — traveled over land to neighboring Turkey in a trip organized and financed by Israel.

Iraq's ancient Jewish community has virtually disappeared, a casualty of the conflict that continues to divide the Middle East. For the last 50 years, Iraq and Israel have been sworn enemies, part of the broader Arab-Israeli conflict. Most of the ancient Jewish community in Iraq emigrated en masse in 1951. But unlike their Arab counterparts, Iraqi Kurds tend to be less suspicious of their former Jewish neighbors. And some Jewish Kurds have begun making discreet return visits to Kurdistan.

Accepting Their Neighbors

Now Lana, 28, is a citizen of Israel who speaks Hebrew and Kurdish fluently. Last year, she returned for the first time since her emigration to live in Kurdistan with her new husband, Hano, an Iraqi Muslim Kurd. The couple asked that their full names not be used for fear of reprisal.

"I didn't think twice about marrying a Jewish woman," Hano said. "My parents always told me stories about how much they liked their old Jewish neighbors."

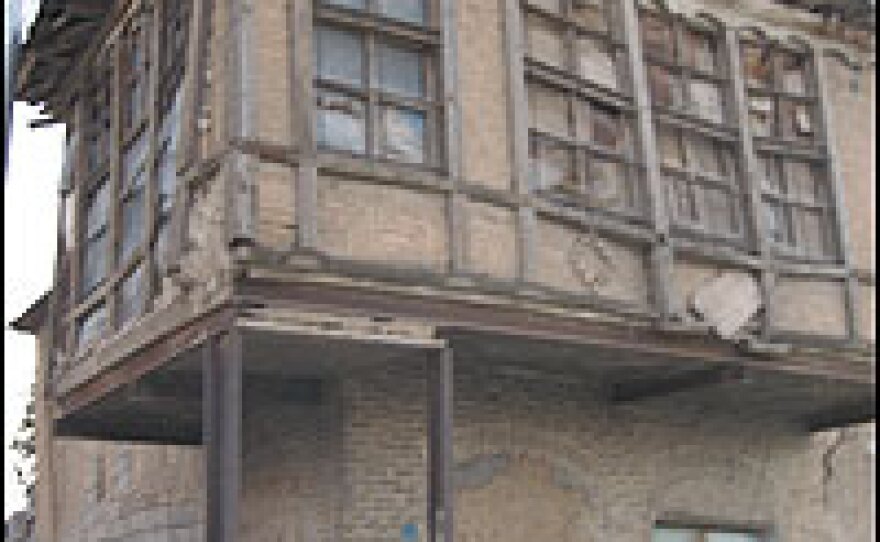

Unlike the Arab majority in central and southern Iraq, the Kurds of northern Iraq don't see Jews or Israel as enemies. In the 1960s and 70s, Israel's Mossad intelligence agency provided equipment and training to Kurdish rebels who were battling the government in Baghdad. To this day, locals call a neighborhood of old sagging brick houses in the Kurdish city of Suleymaniyah, Jewlakan.

A Cautious Return

In the former Jewish quarter of Suleymaniyah, Haji Abdullah Salah, an old Kurdish shopkeeper, says it was a sad day when almost all the Jews left town.

"The government ordered them to leave at that time, and they shouldn't take anything except their own clothes," Haji Abdullah recalls. He says that the last Jew in Jewlakan was a man they called Shalomo, who stayed behind long after the other Jews had left. Locals say Shalomo died in Suleymaniyah a few years ago.

Since the fall of Saddam Hussein, a small number of Kurdish Jews has been making discreet return visits from Israel to the land of their birth. Kak Ziad Aga, 71, says a Jewish classmate from his childhood recently got a warm welcome during a return visit to the Kurdish town of Koya Sinjak. It had been 50 years since he'd seen his classmate.

Ziad Aga says he doesn't see any problem in allowing Kurdish Jews to come back to Kurdistan, but the subject is extremely sensitive for the Kurdish authorities, who are frequently accused by Arab media and Iraqi insurgent groups of collaborating with Israel. The Kurdish leadership denies the charges.

Despite the difficult history for Kurdish Jews, Lana says she's proud of her mixed heritage. "Above all, I consider myself a Kurd," she says. "An Israeli Kurd."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))