There has been a big drop in violence in Baghdad since the U.S. troop surge was launched almost exactly a year ago. But the relative calm that has descended on the Iraqi capital has come at a price. The sectarian divisions there have now been enshrined in concrete and enforced by security groups that mistrust each other.

The place where two Baghdad neighborhoods meet exemplifies what has happened to so much of the Iraqi capital. Huge blast walls line either side of the road running between the Sunni area of Adhamiya and the Shiite area of Qahirah.

The Sunni side is controlled by tribal neighborhood watches. The Shiite area is protected by the Shiite-dominated police. Baghdad has become a maze of divisions and areas of control where religious and ethnic tensions have been subsumed but not eradicated.

Policeman Nabeel Kareem Shamkhi holds a radio. There's been an IED attack, a voice crackles. Shamkhi turns the sound down.

Things are better in his neighborhood of Qahirah, though attacks continue.

"People are tired of fighting, of sorrow," Shamkhi says. "They now started to report anyone who fires a single bullet. We have given people our number and they call us and give us tips. People are fed up."

Qahirah was long controlled by the Mehdi Army — the militia loyal to cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. In tit-for-tat violence during the height of the sectarian battles, bodies would turn up dumped on the streets.

That has changed and there's now a robust police presence. Still, Shamkhi's area of control is limited and is seemingly still restricted by sect.

'No Authority to Go Beyond'

"Al Adhamiya sector is different from ours," Shamkhi explains. "I am in charge of this sector, in charge of this street. I have no authority to go beyond that."

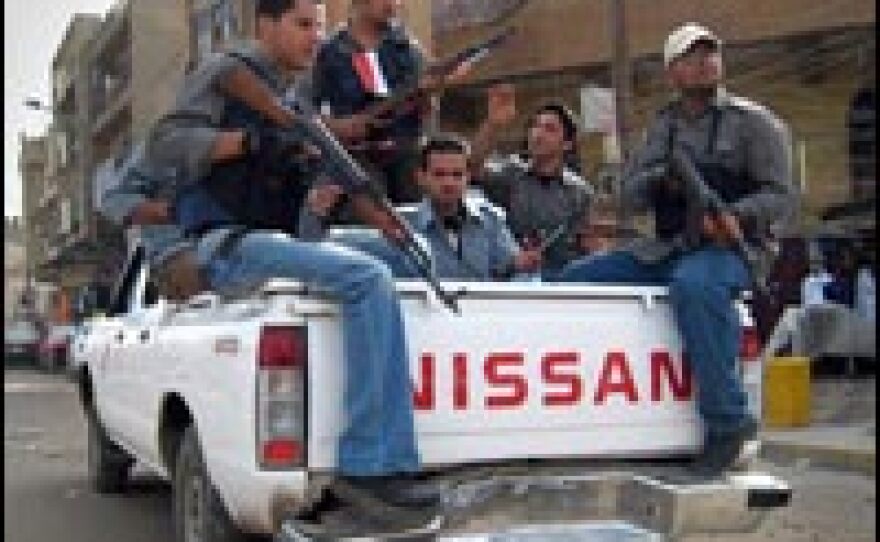

Inside Adhamiya, the awakening groups — U.S.-backed Sunni tribal security forces — hold sway. And Shamkhi doesn't trust them.

"We have no idea about their background," he says. "How can I trust you if I know nothing about your background or who you worked for before?"

It's a concern that residents of Qahirah share.

Majid Ahmed Mohammed sells fat, woolly brown and white sheep at a busy intersection for about $95. A Shiite, he was born and raised in Adhamiya until he was chased out. He tried to go back, but he says he was forced out again by the Sunni paramilitaries.

"The men of the awakening kill people," he says. "I will never get back there till there is a better security situation and the government takes over."

Across the road at the entrance to Adhamiya, cars are stopped by Iraqi army officers. Once through that checkpoint, security is mostly in the control of members of the local Sunni watch groups.

An Awakening Ignored

Ammar Ibrahim Habeeb is among the 700 awakening group members who are in this sector.

He complains that the awakening movement is being ignored by the Shiite-dominated government.

"We didn't receive any support from the government," Habeeb says. "We are getting bigger and many volunteers want to join the awakening, but our numbers have been limited."

The Shiite political class has been ambivalent about these awakening groups. Despite calls to incorporate them into the security forces, they haven't been.

Habeeb says their loyalty, at the moment at least, is not to the government but to the Americans who back them.

"We need the Americans because we don't have enough support," he says. "Our situation is not good. We don't have uniforms and we don't have ammunition."

For the local population though, things are undeniably better in Adhamiya now. Shops are being reopened one at a time.

'The Walls Are Here to Stay'

Still, at a nearby hair salon, Sundus Tariq Yaqoub expresses what many people fear: She doesn't believe that Sunni and Shia will ever be able to live together like they did before. The walls and the divisions they represent are here to stay, she says.

"Everyone had some relative killed and they want to take revenge," she says. "People on both sides want to take revenge still."

A mosque right on the border between Qahirah and Adhamiya calls the faithful to prayer. A month ago, joint prayers were held here bringing together people from both communities.

Still, everyone admits, the peace is fragile right now.

And hidden behind the blast walls and barbed wire, people say, the unresolved issues of the past brutal five years linger.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))