Honduras is seldom in the headlines. But inside its borders, you can see almost every aspect of the global food situation. The crisis is bringing farming in this small Central American country back into fashion.

When it comes to growing food, Honduras is a miniature version of the world. There's even a little bit of Iowa in Honduras' Comayagua valley.

Just like the farmers in Iowa, Rodolfo Rubio is making good profits these days. His corn is tall and green — and genetically engineered.

"With biotechnology, we feel like we're part of first-world agriculture," Rubio says. "We don't have to be jealous of the cornfields of Iowa."

But other cornfields in Honduras could just as easily be in some of the poorest parts of Africa.

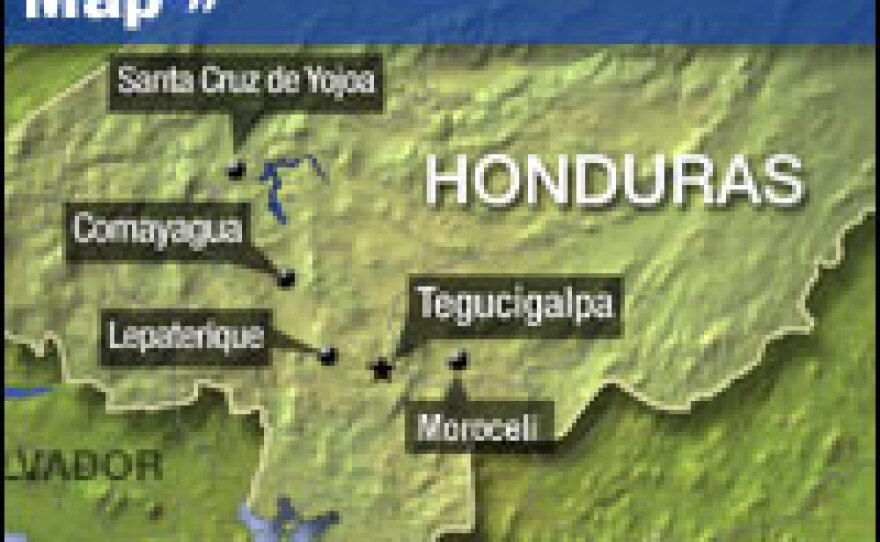

On a rocky hillside near Lake Yojoa, Santiago Gonzales grows corn and beans. He says farmers plant by hand because they don't have the resources to use machinery. And even though he grows food, Gonzales doesn't grow enough to feed his own family year-round. When he goes to the market these days, rice costs twice what it did a year ago — and beans cost 50 percent more.

"Sometimes we eat and sometimes we don't," Gonzales says. "And when we eat, it's very poorly, because our situation is very difficult here. And I can tell you this: We and our children and our grandchildren will have to eat each other when we're hungry."

The story is similar across the globe. Food is expensive and there's not enough to feed empty stomachs. There have been food riots from Haiti to Egypt.

It has forced Honduran government officials such as Arturo Galo to reconsider a lot of things they thought they knew about food and farming. Galo is in charge of science and technology for the Honduran Ministry of Agriculture.

"Twenty years ago, the international institutions told us that there was no sense, you know, in producing grain," Galo says. "We better buy them and bring them from outside. In the last two decades, grain producers went broke."

It seemed that Honduras' traditional farmers — the ones with just a few acres of poor land — could never compete with corn or rice from the U.S., or from Argentina.

So the world's smartest economists told the Honduran government: Growing corn and beans is for losers. Invest your money, they said, in things with a future: textile exports or tourism. And those subsistence farmers will get real jobs in the city.

So the government of Honduras neglected its small farmers. The country now imports most of its corn and rice.

Porfilio Lobo, the leader of the opposition National Party, who's running for president, says those policies now are changing.

"It has to change," Lobo says. "As bad as wars are, it's even more dangerous not to have enough food."

Galo's agency, housed within the Ministry of Agriculture, has begun a massive effort to distribute fertilizer and seeds to 250,000 of the country's smallest farmers — the ones growing corn and beans.

"We believe, in this government, that the first thing we need to do is provide food for our population," Galo says.

There's a lot of skepticism in Honduras about that program. Some critics say the government is trying to buy votes. But it is a signal that farmers aren't forgotten anymore.

This is also true far beyond the borders of Honduras.

Robert Townsend, a senior economist at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., says governments, international organizations and private foundations around the world are putting money into food production.

"It's a global response, and from our own part, we're scaling up our support for agricultural development, particularly in Africa," Townsend says.

The World Bank is sending out agricultural advisers, building roads into previously isolated areas and providing seeds and fertilizer for reasonable prices.

Some of these programs started even before the current food crisis. Now they've become urgent. Townsend believes they will work. Poor farmers can grow more food. What's not so clear is whether they can do it quickly.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))