Extreme temperatures around the world are likely to rise dramatically as a result of global warming, a new study finds. Some heavily populated parts of the world — including the American Midwest — could face heat waves in which the temperature soars above 120 degrees by the end of this century.

These extreme heat waves are likely to kill people and crops alike.

The study, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, found that extreme temperatures will rise two or three times faster than average temperatures. So in Europe, peak highs could go from a sweltering 100 degrees up to 110 or 115 degrees. There's even a chance the mercury could hit Sahara-style highs of 120 degrees.

Temperatures in the 120s could also strike Australia and the American Midwest, according to the study, which used climate-change models developed for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Andreas Sterl says he and his colleagues at the Dutch Meteorological Institute decided to research extreme temperatures because "those are the temperatures we really suffer from."

"If it's only one day, and then it's cool afterwards it's not a problem," Sterl said. "But usually these heat waves last for some days, and it becomes a health problem."

Sterl says the projected rise in extreme temperatures is particularly worrisome in densely populated areas where temperatures can already sizzle.

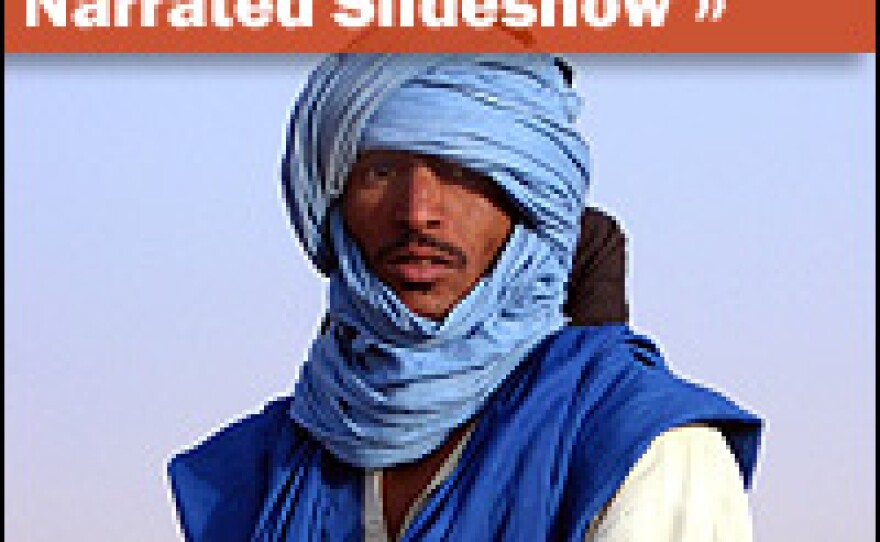

"What I'm personally very concerned about is the Middle East and northern India. It's a heavily populated area and it's already very hot there today. But it will become much hotter there. So they will experience temperatures that will reach [up to] 125 degrees Fahrenheit," Sterl said.

In the United States, many people can retreat into air conditioning during hot weather.

Michael Greenstone, an environmental economist at MIT, has found that a steep rise in summer temperatures may not have that great an impact here. Even agriculture can withstand the occasional high-heat wave, his studies show.

But he says the story's different in India.

"There, it's not very easy for people to turn on the air conditioning or to pick up and move, just because they don't have as many resources," Greenstone said. "My preliminary research on India suggests that the impacts on mortality could be quite dramatic."

Horrible heat waves could lead to mass fatalities, he says. And agriculture is also likely to suffer more in places like India, where it is a large fraction of the economy.

"I think it's becoming clearer and clearer that the costs of climate change won't be spread evenly around the globe. Unfortunately they're going to be concentrated in countries least able to deal with them, just due to low income levels," Greenstone said.

That means there are really two avenues to pursue to prevent massive heat deaths in the coming decades. One is to try to reduce emissions to slow the pace of climate change. The other is to improve the standard of living for people who are poor, so they can better cope with the heat.

Greenstone says, fortunately, there's time to deal with this: "Changes in temperature are not going to accrue overnight. So there will be a lot of time to adapt."

We may find ways to survive the heat. But we may never get used to afternoon high temperatures that are now found only in the planet's hottest deserts.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))