The Obama administration is pledging a major new law enforcement push to try to keep the Mexican drug cartels at bay — both in Mexico and here in the U.S. Violence between the gangs and confrontations with authorities have taken thousands of lives in Mexico in recent years, and there's growing concern in the U.S. that the bloodshed will spill over the border. The administration is even considering sending in the National Guard.

While these moves may increase security along the border, they won't keep the Mexican cartels out of the U.S. That's because they're already here, and well-established.

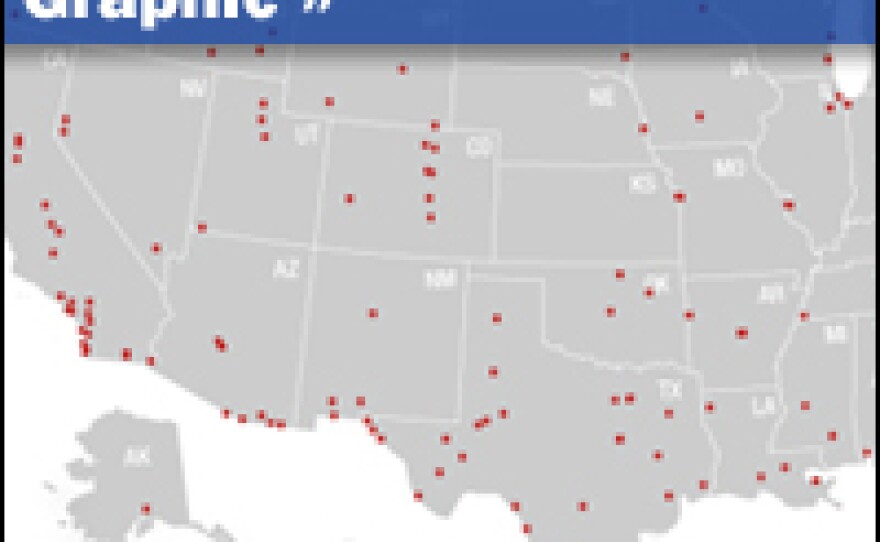

The Justice Department says the cartels now have operations in at least 230 American cities, up from 50 in 2006. Many of those are smaller, agricultural cities with Hispanic communities — places like Mount Vernon, Wash. Less than an hour from the Canadian border, it's the last place you might expect to encounter the Mexican cartels. But Skagit County Sheriff's Deputy Chris Kading says the cartels are definitely here.

Driving through the town's heavily Hispanic apartment complexes, Kading says most Mexicans here are "good people, who work their tails off in the fields." But there's no avoiding the fact that narcotics investigations almost always lead back here.

The Mexican cartels have a near-monopoly on the distribution of wholesale quantities of drugs in most of the country now. Whether it's crystal meth by the pound or cocaine by the kilo, odds are it was supplied by the cartels and sold by their middlemen in places like this. Street-level dealers, on the other hand, often are not Mexican, or even Hispanic.

It's a pattern seen around the country: The cartels use Hispanic communities as cover — small towns like Pocatello, Idaho, and Oklahoma City. But Kading says you won't find the cartel bosses up here.

"These are the storekeepers, the worker bees, the disposable people. If they get caught, they get caught, there's four more who'll take their place," he says.

The Business Model

The cartels' American business plan is almost foolproof: The bosses stay in Mexico, and the money comes to them. Another detective working in Skagit County — who asked to remain anonymous, because he's still working undercover — says the money raised by the wholesale drug business doesn't stay in the U.S. very long.

"We've actually done deals and then watched afterwards as they've gone directly from the deal to the wire transfer place, and we can see our money going back within an hour," the detective says.

That means that when law enforcement raids a stash house in the U.S., there's rarely much money or expensive property for them to confiscate.

The cartels' American business model also benefits from the continued porousness of the southern border. Kading says Mexicans he's arrested on drug cases often come right back to town after their deportation. In one case, he says, a Mexican woman deported after a meth raid came back to town in less than two weeks — and even went to the local office of the state's Department of Social and Human Services to get help reclaiming personal property that had been impounded during her arrest.

Investigators say they're often confounded by changing names and fake ID's. Add to that the fact that many potential informants in the Hispanic community won't talk to the police, for fear of deportation, and it becomes very tough to track the cartels' movements.

A Different Type Of Operations

There's hardly a corner of the U.S. that doesn't have some Mexican cartel presence. The special agent in charge of the DEA's Seattle division, Arnold Moorin, counts at least five Mexican gangs or cartels with operations in the Pacific Northwest.

But while the cartels are here, he says, they don't operate the same way here as they do back home. This is a distribution operation, and they generally don't have the kind of savage turf wars seen in Mexico or along the border.

"For them to be as violent as they are in Mexico, that's counterproductive," Moorin says.

Still, that faraway violence has an effect here; Assistant U.S. Attorney Matt Thomas says he feels it when he tries to get a Mexican to cooperate on a prosecution.

"Chances are, the organization will visit a member of their family. Typically, they might, you know, talk to their mother, say hello, and that gets back to them here," Thomas says.

But in Mount Vernon, no one seems too worried about the cartels bringing that kind of violence this far north. In the Hispanic neighborhoods, the presence of the cartels inspires more shoulder shrugs than fear.

Lucia Ortega tutors Hispanic kids in a small community center on the edge of one of the apartment complexes identified as one of the cartels' distribution centers. She says she knows a couple of people involved in the drug trade but keeps her distance.

"I think they just bring their stuff here, give it to other people to sell, and that's that," Ortega says.

She says she feels safer here than she would in Mexico. Another tutor, Linda de la Rosa, says the only thing that's really changed is that outsiders seem to be more aware of the cartels now.

"I guess it hasn't come out into the open as it is now. I think people are more aware of it, but I personally believe it's always been around," says de la Rosa.

In fact, that jibes with information from the DEA; Moorin says the Mexican cartels displaced the Colombians on the West Coast as far back as the mid-1990s. So the cartels' presence in the U.S. isn't really new. What's new is the level of violence in Mexico, which has made Americans look around and wonder whether that could be on its way here.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))