The story reads like a classic example of British imperialism.

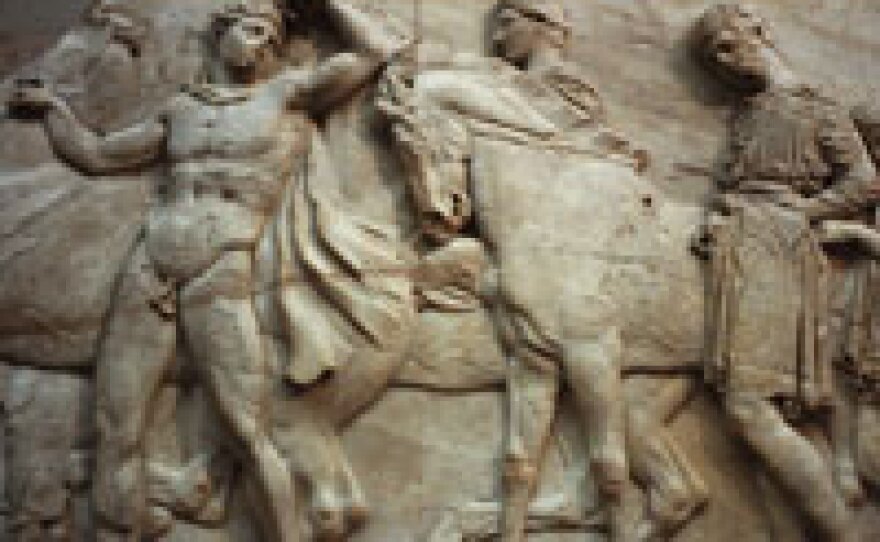

A British diplomat and noble named Thomas Bruce, Seventh Earl of Elgin, was also a noted collector of antiquities. While ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, he obtained controversial permission to remove large sculptures from the Parthenon's wall in Athens, a city that was under Ottoman rule.

Elgin planned to use these antiquities to decorate his home in Scotland. Instead, they were sold to the British government, which then handed them over to the British Museum.

The relics, known as the Parthenon or Elgin Marbles, have remained a controversial part of the British Museum's collection since 1816. Debate continues over the legality of Elgin's actions and whether the Marbles should be returned to Greece.

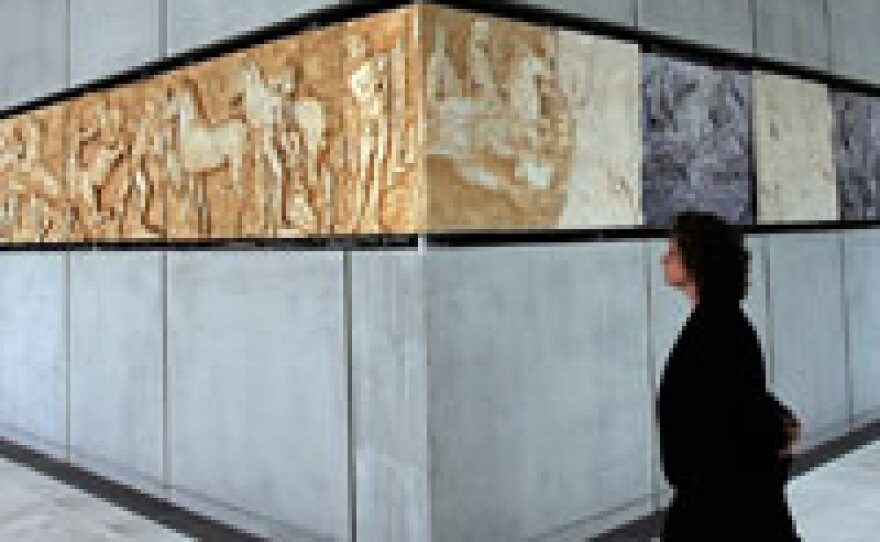

That controversy continues with the opening of a new museum in Athens. The Acropolis Museum has created a display that shows how the sculptures would have looked on the Parthenon itself. Plaster casts fill the spaces where the Elgin Marbles will be if they are returned by the British.

Author Christopher Hitchens, who has written extensively on the Elgin Marbles, thinks the British collection should be returned to Greece.

"If you can picture cutting the panel of the Mona Lisa in two and having half of it in Sweden and half of it in Portugal," he says, "I think a demand would arise to have a look at what they look like if they were put together."

Hitchens points out that other pieces of the Parthenon have been returned by the Vatican Museum, the Italian government and the University of Heidelberg in Germany.

So far, officials at the British Museum have refused.

According to a statement on its Web site, "The current division allows different and complementary stories to be told about the surviving sculptures, highlighting their significance for world culture and affirming the universal legacy of Ancient Greece."

Hitchens disagrees, citing this as a unique case: "There are no Babylonians left, there are no Hittites, there are no Aztecs," he argues, "whereas the Greeks still speak a version of what you can read in the inscriptions in Athens. There's a continuity to the claim there, and that temple is still their national symbol, as it is of the European Union. So, I think it's a very unique case — a live one, rather than a dead one."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))