The arrest of 10 accused Russian agents in the U.S. provoked all kinds of questions about what they were doing here and how well they were doing it. None was charged with espionage, because they apparently never stole any secrets. But while the episode seems dated -- and quaintly Cold War -- it suggests that Russia still sees the United States as a target for espionage.

There are secrets to be had, and Russia's spy service probably has other ways of getting them.

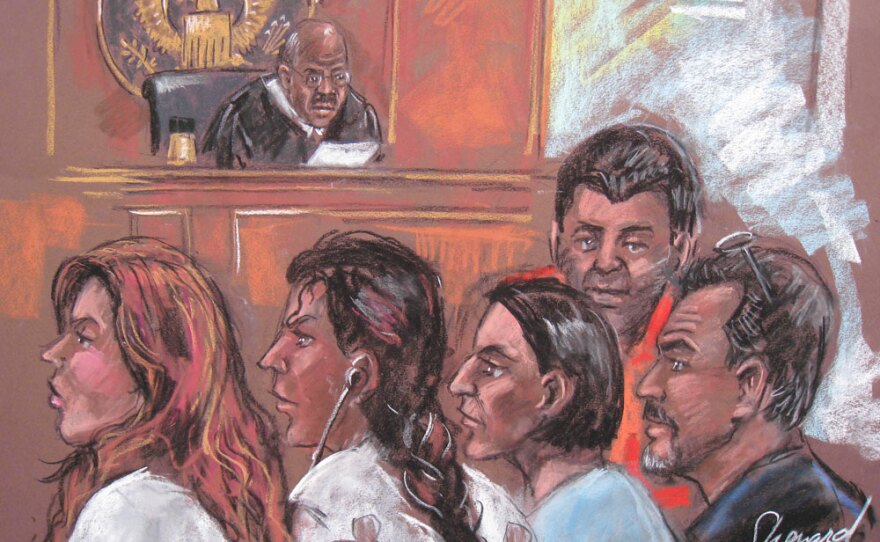

The 10 people arrested have mostly been mocked -- they've become almost a parody of the Russian spy service.

"The kind of information that these folks are coming up with, you can simply get from reading The New York Times, watching TV. You don't need to be investing the tremendous resources to have people undercover for eight, nine, 10 years. It really reflects, I think, an anachronistic mindset," says Andrew Kuchins of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank.

But that doesn't mean that Russian espionage in the United States isn't happening -- and at a much more sophisticated level.

The U.S. intelligence community still hasn't completely recovered from the damage done years ago by two Russian moles: Robert Hanssen and Aldrich Ames. The two U.S. intelligence officials were arrested and accused of leaking high-level state secrets, including virtually all the names of American spies working in Moscow at the time.

What Russian spies are looking for today has changed some from the height of the Cold War. The agenda is broader, says retired Brig. Gen. Kevin Ryan, now the executive director for research at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University.

"I would say nuclear technology is probably not at the top of the list," Ryan says. "Russia desperately needs to improve its economic situation, and they understand that that is their biggest weakness, so they're looking for technology secrets, they're looking for innovation secrets, and some of these things they learn through legal joint ventures and other things they try to get clandestinely."

There are also more traditional geopolitical interests. James Bamford, who writes extensively on intelligence, lists a couple:

"What's the United States going to be doing in the Middle East with regards to terrorism? Or, what's the United States going to be doing in other parts of world where the Soviet Union -- I'm sorry -- where Russia still has a lot of interests. What we do in Iran, for example, it's very important to them because Iran's of great interest to Russia," Bamford says.

So if those are the secrets the Russians want, the question is how they're trying to get them.

There's technology (spy satellites and phantom wireless networks), and there's human intelligence.

Ryan says the Russians place more value on the secrets obtained the old-fashioned way.

"I think at the base of this group is a kind of a suspicion or a lack of trust in the Internet, and in the information that's available in digital form and the Internet. There's a need, or a perceived need, to get this from human-to-human contact," Ryan says.

That's what the Russians are good at, and that's what they continue to invest money in, Ryan says. And just because alleged 10 low-level operatives were caught does not mean the investment isn't paying off.

You don't necessarily know a secret's been stolen until it's too late.

"These people are caught. They're not going to be the ones that are going to get the top award back in Russia -- that's the people who get the top award later, at the end of their career, who we never see. [Those are] the ones that we want to be most interested in finding," Ryan says.

In other words: The good spies don't get caught.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))