In Indonesia, many people are celebrating what they see as a long-delayed victory for justice and human rights. Representatives of a village in West Java that was the site of a massacre by Dutch colonial soldiers 64 years ago sued the Dutch government and won.

The Dutch court ruled that the government must now compensate the victims' seven surviving widows. One of them is 84-year-old Cawi Binti Baisan.

She remembers her husband, Bitol. waking her up before dawn one morning in 1947. Bitol, who went by only one name, had just come in from the rice paddies, carrying his plow.

"'Wake up, wake up.'" Cawi says, imitating Bitol's hushed but urgent words. "Many wives were still asleep," she recalls.

" 'What is it?' I asked. 'There are many Dutch troops at the irrigation ditches,' he replied. 'We're already surrounded.' "

Bitol used the word tuan, referring to Indonesia's Dutch colonial masters. Indonesia declared its independence in 1945, but for four more years, the Dutch fought to hang on to their former colony, known as the Dutch East Indies.

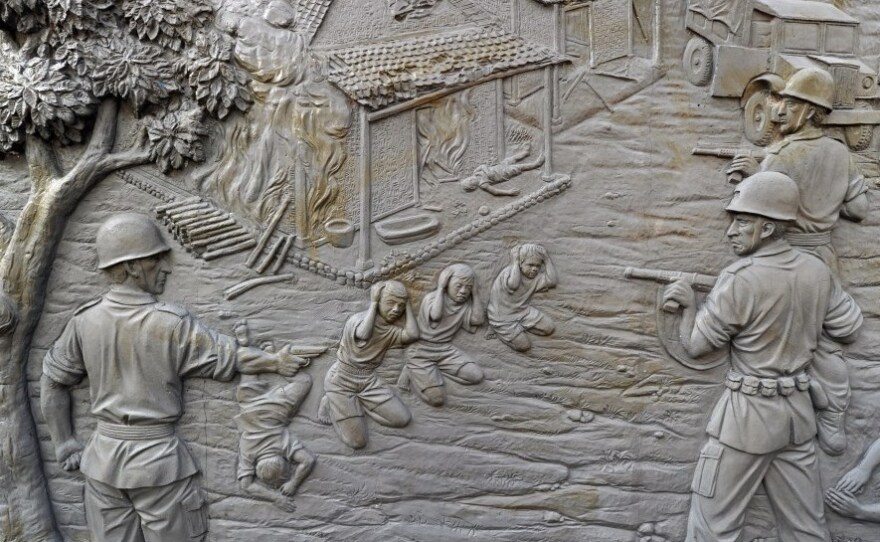

On Dec. 9, 1947, Dutch troops came to Rawagede village — about 45 miles east of Jakarta, the capital — looking for an insurgent leader. The villagers said they had no idea where he was, but the soldiers suspected the villagers were aiding the insurgents.

Cawi mimics the sound of the gunfire she heard, as the soldiers summarily executed all male villagers age 14 or over.

Cawi squats besides Bitol's grave, which is among those of 180 other massacre victims in Rawagede. Villagers say there were more than 400 victims in all, but the rest of the remains are missing.

Cawi's lips quaver as she recalls finding her husband that afternoon, shot to death in a ditch.

"People searched for bodies like this: 'Where is my brother? Where is my husband?' " she says, making groping gestures with her hands. "Like people looking for small fish in a ditch. The surviving men all ran for their lives. For a month, there was not one man in this village."

Legal Case Kept History Alive

The massacre would most likely have faded into history except for the lawsuit, which was filed in 2008 by village representatives and others who were unwilling to let such an injustice go unchallenged.

Liesbeth Zegveld, the Amsterdam lawyer who represented the victims' widows, says Dutch officials reminded her that under Dutch law, there is a five-year statute of limitations for a civil suit.

" 'I know,' " Zegveld shot back. " 'But you also know that you're still dealing with the claims of Jewish relatives that suffered damage in the second world war, so you do still take up claims from that period.' "

There were many cases like Rawagede. Hundreds of people, even thousands of people being persecuted, killed, targeted for torture, many human-rights violations, but unfortunately, no accountability has been taken.

Dutch opposition lawmakers supported the lawsuit. They argued that if the Netherlands aspires to be the international capital of justice, then it should be able to take a dose of its own medicine.

In fact, the Dutch government long ago admitted to the killings and donated money to the village of Rawagede. Zegveld says that a lawsuit could have been avoided if the Dutch had linked that payment to the massacre — but they refused.

"It acknowledged from the first day that crimes have been committed, and then they remained silent for the next 60 years," she says.

How much compensation the widows will now receive has not yet been determined.

Culture Of Impunity Persists

War crimes victims suing perpetrators in court is a fairly recent development. Traditionally, such matters have been settled between governments.

But Jakarta has avoided any involvement in the Rawagede massacre case.

Haris Azhar, a human-rights advocate with a group called the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence, says that the government wants to avoid responsibility for atrocities committed in the post-colonial era.

"There were many similar cases like Rawagede," Haris points out. "Hundreds of people, or even thousands of people being persecuted, killed, targeted for torture, many human-rights violations, but unfortunately, no accountability has been taken."

It's been more than a decade since the fall of the military dictator Suharto, Haris says, but his culture of impunity for past human-rights violations lives on.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))