CAVANAUGH: Our top story on Midday Edition regards the latest research into how climate change could actually make us sicker. The complex interconnection of how plant, animal, and insects thrive on our planet is just beginning to be unravelled by scientists. One thing that a warming planet will do is to change that balance and make it rise to an alarming increase in infectious disease. My guests, Stanley Malloy is professor of microbiology and dean of the college of sentences at San Diego state university. Welcome to the program. MALLOY: Thank you very much, Maureen. It's wonderful to be here. CAVANAUGH: Alan Sweedler always joins you, director of SDSU center for energy studies and environmental sciences. Welcome to the program. SWEEDLER: Thank you, Maureen. Pleasure to be here. CAVANAUGH: Professor Malloy, the discussion take place tonight about climate change and infectious disease is part of a series of events commemorating the 50th anniversary of Rachel Carson's book, Silent Spring what. Connection do you make between this discussion tonight and that book? MALLOY: The idea behind silent spring was Rachel argued when we mess with the environment, in some cases but putting toxins into the environment or insecticide, we mess with the whole ecology of the system. So by adding an insecticide, we could have a long-term effect on animals and people. The whole idea of silent spring came from the insecticide DDT. And the title comes from the argument that this would kill not only the harmful insects but the beneficial insect, and it would get into birds. Can you imagine a spring where you don't hear the chirping of Cricket, where you don't hear the singing of birds? We would lose a lot in the process of trying to use something that would eliminate some harmful things. CAVANAUGH: And a lot of people trace the modern environmental movement to this book, silent spring. Do you see that as our first environmental warning? And what do you see between the connection to that and what we know now about climate change? SWEEDLER: Well, it certainly had a very strong impact when it was published in 1962. And it -- I remember myself at that time reading it and being quite impressed with the writing style and her scientific rigor. But there have been in the case of climate change which we'll talk about today, there were people working on that in the 19th century. In Europe there were quite a few environmentalists in many places, and the United States. But what Rachel Carson's book did, it was very popular. She was also a well known nature writer before that. She wrote about the sea. She was very committed. And she pointed out the intricacies and the interrelations of things, which was not so prominent before. Rather than putting them into compartments. And that's very relevant for climate change. Because as Stanley mentioned, if you put certain pesticides into the soil, you affect the insects but you also affect the birds. But when you put certain gases into the atmosphere, the whole earth is affected, every single human being because you're dealing with the atmosphere, which everyone uses and breathes. So there's a direct connection and relationship there. CAVANAUGH: And sometimes those connections are so complex that even when you do something that you think is a good idea, there are unintended consequences, and professor Stanley Malloy, I'm thinking about Rachel Carson's indictment of DDT. That pesticide was not used anymore in the United States and possibly across most of the world. But what were the unintended consequences of that? That's the subject of a lot of your study. MALLOY: Well, by not using DDT, it prevented the toxicity that we see for example in a lot of large birds and mammal, but it also allowed the mosquito population to be vectors of disease to increase. That was such an effective method of controlling mosquitos. CAVANAUGH: And with the increase in the mosquito population, have we seen an increase in the amount of insect-borne illness in recent years? MALLOY: Well, insect-borne illness has continued to be a major problem across the world. Take for example malaria, it is transmitted by mosquitos. It is a major killer in Africa, and a lot of other parts of the world. And in theory, if we had been able to keep using DDT at very high level, we would have been able to bring the deaths due to malaria down by diminishing the mosquito population. CAVANAUGH: On the other side of the coin, we don't want know what deaths might have been caused by the toxicity of that pesticide. MALLOY: That's absolutely right. We know that the pesticide causes developmental defects in birds and animals. We presume that there would also be impacts on human development. We're also a mammal. And so it's one of these things where we decreased one problem but we would have caused another very serious problem. CAVANAUGH: When it comes to the increase in the insect population, there's also another side to this or a corresponding, parallel event taking place, and that is an increase in the world's temperature. According to a world bank report, the world may be headed toward an increase of temperature by 4 degrees. Now, professor Malloy, you say the single-digit changes matter, especially when it comes down to how infectious diseases spread. And I would imagine how far it spreads. MALLOY: Absolutely. So this is one of the things about climate change. Some people will say oh, these are little tiny changes. We're not going to have to worry about this for 50 years or 100 years. Why should we hurt the economy now to deal with these kinds of problems when they're not problems that will happen in our lifetime? I think there's an ethical issue there about causing a problem for later generations. But it's also incorrect that the small differences don't matter. So a 1-degree change in temperature is enough to influence the development of the malaria parasite inside of a mosquito. Whether it develops or not develops can be determined if the temperature is 15 degrees or 16 degrees. CAVANAUGH: And Alan? SWEEDLER: I think an important point to make here is that here is where there may be a difference between the DDT and the pesticides and climate change. And related global warming. The global warming process has begun. It cannot be reversed. You cannot take it back like you can stop using DDT, or even with the case of the ozone layer. But in the case of climate change, and particularly its related warming, the gases we're talking about primarily are in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. We cannot reverse what has already begun. And the point to keep in mind about global warming isn't that the earth is warming. It's how fast it's warming. The rate of change. And that is unprecedented. There have been warm periods and cold periods in the world. But they have lasted for tens of thousands of years. We are seeing changes in the last 100 years which are unprecedented. CAVANAUGH: And one of the points I think that you make is not only are these warming agents in the environment for hundreds of years, but we continue to add to them; is that right? SWEEDLER: Very much so. And despite all of the efforts and treaties around -- or one treaty, the Kyoto treaty, emissions, particularly of carbon dioxide have in fact increased. They went down a little bit because of the recession. But now they're going up again. And the warming of both the United States and the world, those are observational facts. Those are experiments that are made, satellites, sensors in the ocean, probably billions of data points by now are analyzed, and the trend is very, very clear. There's no doubt that the earth is warming. There is still some discussion about the causes of it, although that is becoming much more refined as well. And I would like to make just one more point to get it on the table, Stanley pointed out that there may have been some -- in the case of DDT, we don't know if there would have been things that happened. In the case of global warming, people say it's going to hurt the economy. I would argue the opposite. The challenges presented by the attempt to reduce the use of carbon-based materials are a fantastic opportunity. They can create new types of industries and jobs, and at the same time address this, why. So it's not at all obvious that this is an economic hardship. It could be an economic opportunity. CAVANAUGH: Stanley, I just want to follow what you told us a minute ago about the fact that a tiny difference in temperature can make a difference as to whether a mosquito develops malaria or can transmit it. Do changes in temperature also affect how far the mosquitos would be able to transmit it? We know a zone in the global where malaria exists now. Do you expect with global warming that zone will increase in diameter? MALLOY: Absolutely. One of the places you tend to have lower temperatures at lower altitudes, on mountains. And with global warming, the temperature is increasing to a higher level. And we're seeing an increase in the number of mosquitos at higher elevations as well, and the transmission of disease. The other thing is that they're moving to higher latitudes. So we're beginning to see some of these mosquitos moving up into areas of the United States and of Europe where we haven't seen a problem for quite a while. And so this is a real problem. We're just beginning to see these effects right now. If you do modeling, if you make predictions and you say, well, what happen fist we change one more degree? Then even further, up north into these areas where we haven't really seen some of these mosquitos-borne diseases. CAVANAUGH: Since tonight's discussion is being sponsored by the center for ethics in science and technology, is it fair to assume that you see that there's an ethical dimension to the issue of climate change? SWEEDLER: Very much so, ethical and moral. And we can use the analogy with Rachel Carson and the silent spring, the ethical issue there was the impact on in this case birds through the weakening of the shells. I would argue in climate change, we're orders of magnitude beyond that, and the ethical issue is the human population. We are affecting the atmosphere that every single living thing on earth breathes. But the people who are going to pay the consequences, they have had no input into this. Most people don't decide what fuel goes in their car or what fuel is burned to make their electricity or what agricultural policy is. But if those activities together contribute to a significant change in the climate and a warming -- CAVANAUGH: And a significant increase in their chance of becoming infected by illnesses. SWEEDLER: Exactly, exactly. They have had no say in that. And that's why the major churches of the world have looked at climate change as a moral issue. Because in fact that's what it is. Who decides this? Who decides the amount of gases that are put in? How is it decided? I don't have the answers to those questions. But that certainly should be discussed. CAVANAUGH: And it's one of the things that will be discussed tonight. SWEEDLER: Yes. CAVANAUGH: A nice segue there. It takes place today at the Ruben H. Fleet science center, it's free and open to the public.

The latest research into climate change suggests that global warming may impact the spread of infectious diseases. The complex interconnection of how plants, animals and insects thrive on our planet is just beginning to be unraveled by scientists. But one thing that a warming planet will do is to change that balance, and may give rise to an alarming increase in infectious disease.

The Center For Ethics in Science and Technology is hosing the 2013 Silent Spring Series, which is commemorating Rachel Carson's book, Silent Spring. This year the program includes a number of talks on global warming.

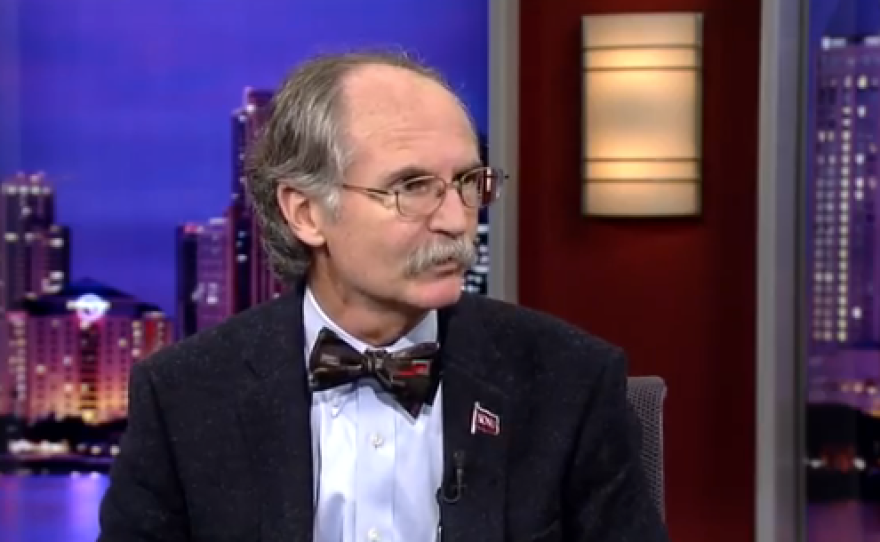

The Center is hosting it's fourth talk of the year Wednesday night at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center. It features speaker Stanley Maloy, Dean of College of Sciences at SDSU, who will be tackling the connecting between global warming and infectious diseases.

"Climate change has a number of direct and indirect consequences, causing shifts in the natural habitats of animals and plants as well as the emergence and spread of many infectious diseases," he said.