Drug tunnels are not the only passageways beneath the U.S.-Mexico border that transport valuable cargo. Pipelines cross the boundary too, carrying natural gas south.

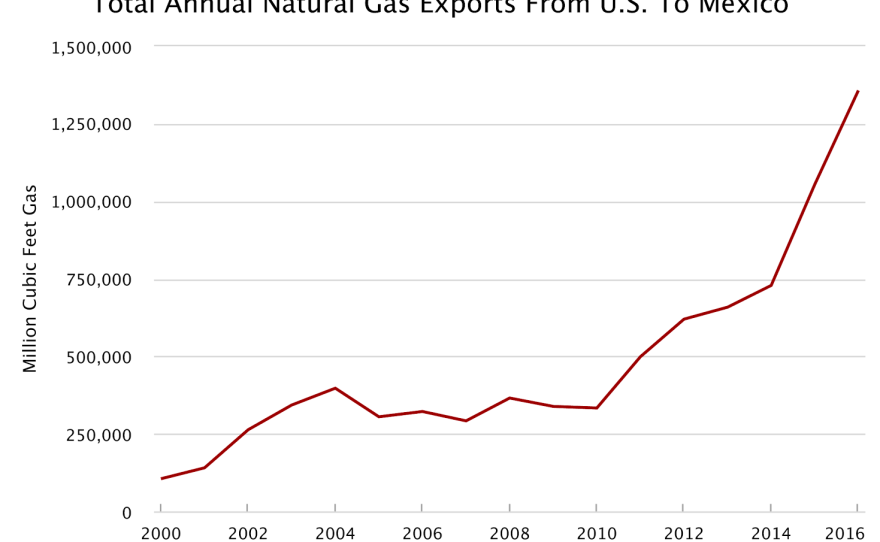

This trade is up 300 percent since 2010, and now it set to double again by 2019. It’s the largest natural gas export capacity expansion in U.S. history, said Victoria Zaretskaya of the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“You saw just a bonanza of infrastructure,” said Jeremy Martin, vice president for energy and sustainability at the Institute of the Americas, a think tank at the University of California San Diego. “The natural gas imports into Mexico have doubled every year for the previous three years. Projections continue to be blown away.”

17 gas pipelines enter Mexico from the U.S. Four more are in development.

The natural gas has allowed Mexico to shift its source of electricity and factory fuel. Electric power and industry converted from burning diesel fuel and other oil products to natural gas. Now Mexico imports 60 percent of its natural gas from the United States, according to Zumma, an energy consulting firm in Mexico City.

That dependence is causing for concern in Mexico, given the disregard for the bilateral relationship evinced by the Trump administration.

“Definitely there is a level of worry,” said Jonathan Pinzón, a partner at Zumma. “In government and industry circles, they are discussing alternatives, whether gas can be brought from other regions. It’s a very important discussion to keep having, now that trade between the two countries is being re-examined.”

The worry about dependence is a real reverse, Martin said. “For years the idea of energy security was, if you were interdependent you were better off.”

But the concern in Mexico is also tempered by the knowledge that protectionist measures would hurt powerful American energy firms. Without Mexico, the gas might have no customer. That could cause gas prices to fall further. They have been low for several years.

“It would cause a lot of problems in the producing regions, like Texas. In that sense I think it would be political suicide for the current administration to put any restriction on that gas moving to Mexico,” Pinzón said.

The amount of gas is not trifling. It makes up five percent of U.S. production, Martin said.

Experts are in agreement that Mexico is likely to retaliate against trade actions it sees as unfavorable.

Sempra Energy, the San Diego-based Fortune 500 natural gas and electricity holding company whose subsidiaries serve most of Southern California, has significant business across the border.

The company declined an interview. Its subsidiary IEnova has invested $7 billion in energy infrastructure in Mexico over the last two decades. When current projects are complete, it will have more than 1,800 miles of natural gas pipeline in the country, spokeswoman Paty Mitchell wrote in email.

Mexico’s conversion

The pipeline rush south resulted from two developments. Around the year 2000, Mexico began a concerted conversion from diesel fuel to cleaner burning and more efficient natural gas.

Six years later, fracking and horizontal drilling produced so much natural gas that low prices became a problem. Mexico’s own natural gas production was falling. The country found its northern neighbor eager to sell. The gas was a bargain and for U.S. producers it helped support the price.

Most of the existing and planned pipelines run through Texas. Gas from the Eagle Ford Shale and Permian Basin courses through them, though gas could enter the pipeline system from other fields.

There are crossings in California: Sempra has one near Otay Mesa and another near Mexicali. TransCanada has a pipeline crossing near Ogilby.

Climate and air

Mexico’s switch away from diesel and other fuel oils has reduced emissions that cause climate change, and improved air quality.

But some don’t see new pipelines as climate progress.

“There seems to be a certain degree of escapism,” Gary Hughes of Friends of the Earth told leaders from the three North American countries at a climate symposium in Sacramento in January. “Because the evidence is clear. We need to stop these pipelines and we need to keep this fuel in the ground.”

The early pulses of climate change are strengthening, though most North Americans’ lives remain little disturbed. Last year was another hottest year on record. Global average sea surface temperatures were also the warmest on record. Sea ice hit startling lows.

David Carlson, director of the United Nations World Climate Research Programme, said last week with the release of the latest World Meteorological Association update, “We are now in truly uncharted territory.”

Natural gas is mostly methane. Methane is a powerful, fast-acting greenhouse gas. Under a new law passed in the wake of the the Aliso Canyon natural gas well disaster, companies must report their leaks. For 2015, an estimated 6.6 billion cubic feet of gas was lost through leaks, even more than the 5 billion released at Aliso Canyon. Methane emitted from oil and gas facilities, as well as from agriculture and landfills, is responsible for a significant portion of current climatic change.

California has prioritized addressing leaks from oil and gas facilities, finalizing new regulations just last week.