This story is part of our series “Trump Ed,” exploring how President Trump’s proposed federal education policies could impact California schools. The series was produced in collaboration with reporters from KQED, KPBS, KPCC and CALmatters.

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has compared private schools to the ride-hailing app Uber and public schools to traditional taxis. Where one's sleek and nimble, she says, the other is rickety and slow to change.

Her school voucher proposal — giving parents direct federal dollars to send their children to a private school of their choice — is meant to change all of that that through market competition. But parents hoping for a slick ride for their kid’s education might want to think again.

Also like Uber, the schools most likely to gain from the new administration's policies are wary of the government regulation that may come with federally funded vouchers. And that makes many private schools unlikely foes of the vouchers many thought would help parents pay for a private school option.

"An independent school is just that. We are independent," said Kim Cooper, director of admissions at The Bishop's School in La Jolla.

While Bishop's board has not yet weighed in on vouchers, the National Association of Independent Schools says the vast majority of its members are unlikely to accept them. Very few do in states that already have such programs.

Of the handful of San Diego independent schools KPBS surveyed, none said they would take vouchers. That closes any new doors a federal voucher program might open to San Diego's most coveted schools.

'If it ain't broke…'

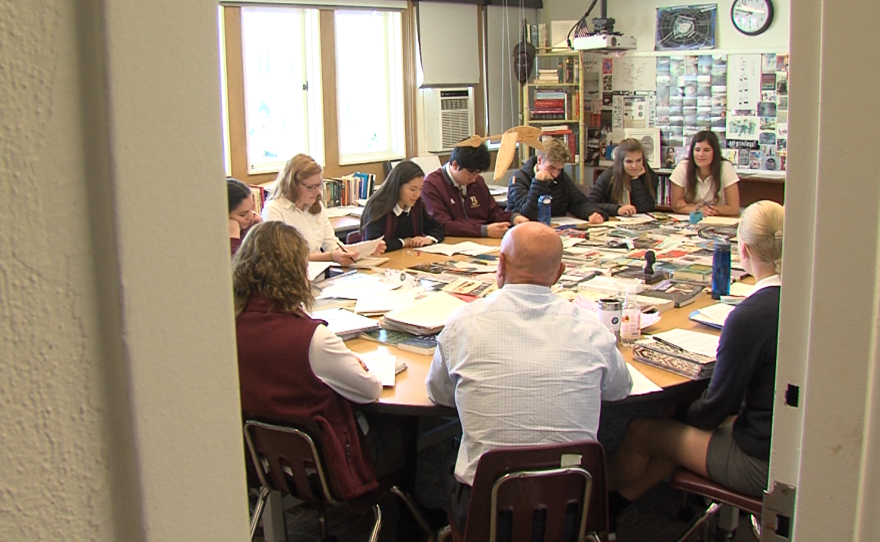

If private schools are to school choice what Uber is to ride hailing, then Bishop's is a luxury Uber Black. The 108-year-old campus is filled with the scent of flowers, chirping birds and rich history. Open the door to a classroom and it is like your favorite college professor's office — full of books, ephemera and great discussion.

The classrooms are small like an office, too, built to perfectly fit about a dozen students around an oval table. The school enrolls 800 students and keeps a lengthy waiting list.

"You really have the opportunity to really engage with your teachers to really experience that learning," said Tamika Lipford, who graduated from Bishop's in 2005 and went on to become a military prosecutor.

She recently came back to the school to give the keynote address at its annual fundraiser, which brought in $1 million for tuition assistance. Each year, Bishop's awards $3 million in financial aid to 20 percent of its students. It costs more than $33,000 a year to attend.

Lipford was herself a financial aid recipient. One of seven children, she expected to go to El Camino High School in Oceanside before Bishop's basketball coach recruited her.

"There's a stark difference between where I went to middle school, Martin Luther King Middle School, and the actual high school I would have gone to, El Camino." Lipford said. "The focus there would have been on athletics, not so much on academics. Whereas, at Bishop's the focus is on academics and making sure you excel in that area, and then having athletics come second."

Lipford said that focus was a result of small class sizes, personalized instruction and daily contact with an adviser. She said she worries throwing a school choice initiative into the mix would ruin all that.

Cooper, the admission's director, agrees.

"We have an admission process and that process is to enroll the most qualified students who would fulfill the mission of our school and be mission-appropriate. That's where our focus is, not on affordability," she said, adding that the school's fundraising efforts allow it to recruit diverse students from all socioeconomic backgrounds.

Wary of regulation

Myra McGovern, the vice president of media for NAIS, said Bishop's has reason to believe a voucher program might change things on campus. She said vouchers could come with regulatory strings attached.

Some existing voucher programs require student beneficiaries to take standardized tests. Schools worry that may bleed into curriculum by encouraging schools to "teach to the test." And vouchers are often awarded through lotteries, complicating a system whereby independent schools first admit students whom they believe will excel in their school model and then figure out financial aid later.

McGovern added that independent schools have even less incentive to take vouchers because they likely wouldn not cover the full cost of tuition.

So would parents gain access for their children anywhere under a voucher program?

Parochial schools in need of fixing

The Spanish archways and chirping birds at Blessed Sacrament Catholic School in San Diego's urban core echo those at Bishop's. But look closer and you'll see an abandoned preschool playground and peeling paint on a statue of the Virgin Mary.

"This was, at one time, one of our powerhouse Catholic schools," said John Galvan, the head of schools for the Catholic Diocese of San Diego County. "Founded in 1947, it currently has 114 students."

That is about half its capacity.

On a tour of the school, Galvan stops at the trophy case. The years etched in brass stop around 2005.

"Blessed Sacrament is in a position where they don't have enough students to field sports teams," Galvan said. "And what's ironic about that is you have two Hall of Famers — college basketball with Bill Walton and Phil Mickelson, a professional golfer — they both graduated from this school."

Galvan says it is the cost. A lot of families cannot afford to pay $5,000 a year for elementary school and $15,000 for high school. The diocese has a financial aid fund filled by parishioners, but it taps out at $1 million. Last year, Galvan calculated there was $16 million in need.

"Historically, parish schools were built in this country to serve poor, immigrant families," Galvan said. "The parochial model in its current form, in most cases, cannot survive."

Galvan is not comfortable saying his schools would accept vouchers without seeing a plan on paper, but they are the ones most likely to. They have experienced a sharp decline in enrollment nationwide, so they have the space. And they already take federal education dollars for low-income children and professional development, so vouchers are not as far of a stretch.

Galvan said school choice, generally, is good for parochial schools — and for parents.

"The value of Catholic education — moral and character development, leadership development, a sense of responsibility ethos for others, a safe, caring environment where students are known and loved — those are all reasons why our families choose our schools," Galvan said, adding that nearly all of his students graduate high school on time, many going on to impressive universities. "So with the question of school choice, that's something we certainly advocate."

Still, Galvan is hesitant to give vouchers his blessing for fear of government influence. He and his colleagues in the California Catholic Conference, the lobbying arm of the Catholic community, favor tax credit scholarships. That is what they are lobbying for in Sacramento — tax credits that incentivize donations to a private scholarship fund.

What about public schools?

Back at Bishop's, Tamika Lipford shares her vision for how to give more children the successful education she received.

"I think that it would probably be appropriate to bring public schools up to the caliber of Bishop's, just so any individual student that is in a public school actually has the opportunity," Lipford said.

Keri Peckham, a lead organizer on Bishop's spring fundraiser, underscored the current need at public schools. She also helped organize the fundraiser for her children's school in the Poway Unified School District (they are too young to attend Bishop's). The top item on their wish list was a physical education teacher, she said.

Despite pushback from parents, public schools — even private schools — President Donald Trump and Education Secretary DeVos continue to push for a voucher program. Meanwhile, Congress is looking at tax credits that could gain more traction among private schools and voters.