Securing the border is one of the Department of Homeland Security's most important jobs, but as with everything the agency has tried to do, balancing security with freedom and the economy hasn't been easy.

Critics say the border is still like a sieve in many areas. But efforts to close the gaps have run into strong resistance.

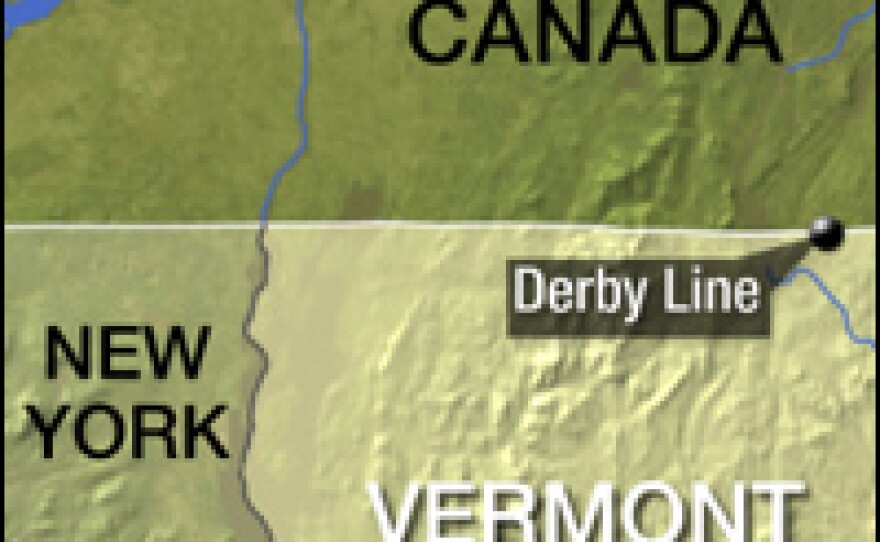

Take Derby Line, Vt.

For many in the tiny town of Derby Line – one of the northernmost points in Vermont — Canada is literally across the street. It's where friends and relatives live, where you go to shop or pray.

Derby Line resident Roy Davis stands on a windswept hill near his farm and points to a stone block poking out of the snow.

"That granite marker right there is on the border between Canada and the U.S.," Davis says. "We don't think anything of being two countries. It's all one country as far as we're concerned."

Roy and his wife, Shirley, bemoan changes taking place here. The border checkpoint used to be little more than a formality. Border officials would often wave and smile and that was it, according to Shirley. But last year, residents suddenly began to face much more intense scrutiny. Cars were routinely searched, familiar faces gone.

"They've treated us just as if we were convicts every time we crossed," Roy says.

"It's eased up a little bit now, though, but you have to get your ID out, and you have to open your trunk. So different than it used to be," Shirley says.

Shirley says she thinks twice now about going into the neighboring Canadian town to buy sugar.

Residents of Derby Line are worried about life after Jan. 31, when Americans are supposed to start showing not only a photo ID but also proof of citizenship — such as a passport or birth certificate — to cross the border.

DHS says it needs to know who's entering the country to keep it safe.

But there's a lot of confusion here about what lies ahead.

Buz Roy, owner of Brown's drug store in Derby Line, asks town trustee Keith Beadle what happens if he forgets his papers when he's trying to return home from a visit to Canada.

"They can't exclude me from my country. They can give me a hard time, but they can't exclude me," Roy says.

Beadle says he did not know what would happen.

Beadle acknowledges that smugglers can and do use local side roads and nearby fields to sneak illegal drugs and immigrants into the country. And while terrorism is a concern, he thinks the government should be improving intelligence instead of clamping down on local residents.

"I realize that we have to be mindful of security, but I think you have to do it in a thoughtful and logical manner, and not just circle the wagons and give everybody a gun to protect themselves."

Policies Here to Stay

Homeland Security has been trying to work with locals to address some concerns and recently eased the "search every trunk" policy. It also gave supervisors discretion to conduct fewer name checks if traffic is backed up.

Jim McMillan, the Customs and Border Protection port director at the Highgate Springs port of entry, says the young agency is trying to develop the policies that work best.

McMillan thinks people will find that some changes — such as the passport requirement — will make things easier, because customs officers will be able to electronically scan information they now type into the computer. That should speed things up for travelers.

His supervisor, Kimberly Nott, says she realizes the agency has a big selling job to do. She knows it's hard for local people to deal with the new procedures, but that they're here to stay.

"They took care of all the big ports and got all the security things there, and now it's starting to come here," Nott said.

Homeland Security officials say they sometimes feel damned if they do, damned if they don't: Everyone complains about security gaps, then objects when anything's done about it.

Problems at the Border

But even some Customs and Border Protection officers are unhappy with what's going on along the Vermont border. They say they're understaffed and overworked, and turnover is high.

John Wilda retired recently after 33 years as an officer at the Vermont border. He was also the local union rep.

"People are leaving because morale is so low. They don't enjoy the job anymore. It isn't the same. There's no respect for what people do," Wilda says.

Wilda says customs officers used to have more discretion, using what he called the "sixth sense" to determine whether a person was telling the truth.

But now agents rely on documents and technology. Officers simply scan documents, see if they check out, and then let the person cross, he says.

"You don't have the opportunity to really talk to people any more," Wilda says. "The sixth sense is the thing that really broke a lot of cases for us. When you would sit there and talk to someone — it's the nervousness, it's the shifting eyes, it's the carotid arteries."

But Nott says technology gives officers more time to focus on those things. And sometimes, she says, it's good to shake things up: After the agency started rotating officers in from out of town, there were new arrests.

"And they were all frequent crossers," Nott says. "People say, 'That's such a nice guy. He crosses all the time.' Well, now you know why. He had narcotics."

But DHS also faces strong opposition from businesses and lawmakers all across the border who worry that new security measures could destroy exactly what the country is trying to protect.

"They were thinking, 'security, security, security, security.' They weren't thinking 'economy, economy, jobs, people's livelihoods, healthy communities,'" says Bill Stenger, president of Vermont's Jay Peak ski resort.

Stenger says he thinks changes at the border are much more likely to stop the Canadians whom his business and many others in the area rely on, than a determined terrorist.

If it becomes too hard to enter the U.S., Canadians may just avoid Jay Peak and stick with one of the many resorts in Quebec, he says.

Recently, DHS worked out a deal with Vermont and other border states to allow secure driver's licenses to be used instead of passports for some crossings, and Congress has delayed a more stringent passport requirement.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))