One of the key issues for a health care overhaul is how to pay only for necessary care — and how to identify which procedures and treatments are most advantageous to patients. Two studies published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine show how difficult making medical decisions based on comparative effectiveness can be.

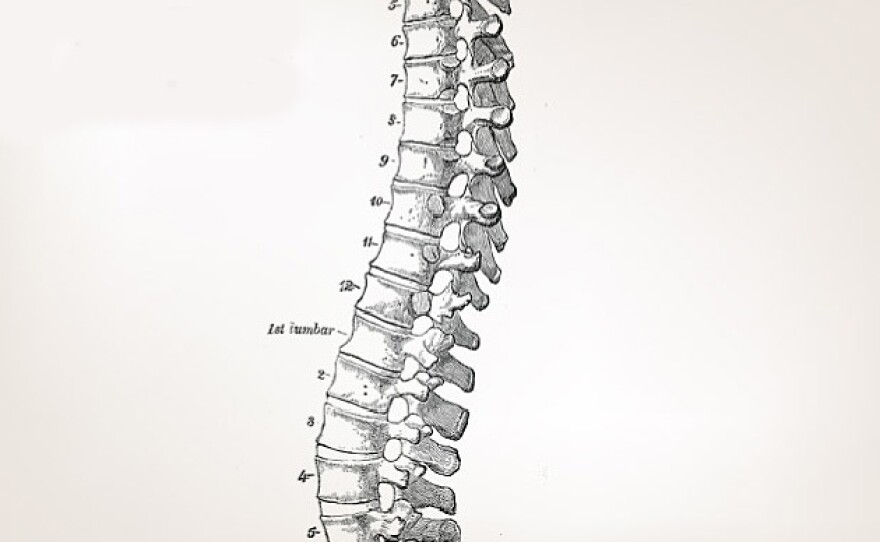

The studies evaluate a popular procedure for treating fractured vertebrae called vertebroplasty, where doctors inject cement to patch up the fractured area. Neither study found a significant advantage to using the cementing procedure compared to the placebo group, which only received an injection of a short-acting anesthetic like Novocain.

When doctors began using the procedure a few decades ago, it seemed like a miracle: By shoring up broken vertebrae with cement, doctors could offer pain relief to people with one or two cracked vertebrae from osteoporosis. The procedure was easy and caught on like wildfire.

Radiologist David Kallmes of the Mayo Clinic was one of the first people to do this procedure in the United States about 15 years ago. But after awhile, he and others decided it needed to be rigorously tested.

"This procedure is done in 75,000 people a year," he says. That's three-quarters of a million people over 10 years. "We should know for sure that it works," says Kallmes. The cement injection procedures cost about $2,000 to $3,000, he says.

So Kallmes designed a study to see if the cement injection was really helping patients. In his study, 68 people got the normal procedure:

"What that entails is giving them sedation by vein, putting Novocain under their skin and on their bone, and then introducing a medium-size needle and injecting this medical cement," says Kallmes.

The 63 people in the placebo group had the same procedure, but without the cement injection. The patients rated their pain before and after. Both groups had less pain after the procedure.

"I wasn't completely shocked when I saw the data, but I frankly was surprised that the results in both groups were so similar," says Kallmes.

A second study from Australia of 78 people, in which half got the no-cement procedure and the other half got the cement injection, also showed no significant advantage to the cement fix.

The head of the North American Spine Society says the broken vertebrae studies show that both the placebo and cement procedures work.

But some interpret the findings differently:

"What it said to me is that essentially this is a treatment with no effect, and it probably shouldn't be done any more," says James Weinstein, an orthopedic surgeon who directs the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

Weinstein is a proponent of comparative effectiveness — comparing various treatments to see what works best. Another factor in considering whether to perform vertebroplasty is the possibility of complications: The cement can get into a vein or push on a nerve.

Many have questioned the effectiveness of various other back pain procedures. For example, long after surgeries for slipped disks had become common practice, it was determined that the surgery has only a slight advantage over rest and rehabilitation. Spinal fusion also remains controversial. In many cases, the passing of time alone can heal the back.

"We do need to today have these kinds of studies done before we implement these strategies in clinical practice," says Weinstein. "And where we can't do them because of funding or support or for whatever reason, maybe we ought to think twice about introducing them into the common marketplace."

President Obama has set aside $1 billion to do comparative effectiveness studies. It's a good idea, but it's going to take some discipline to make use of the results, says Sean Tunis, director of the nonprofit Center for Medical Technology Policy. He says insurers will have a hard time disallowing procedures that the medical community thinks work.

"And what you've gotten into is what everybody is uncomfortable with, which is that either a payer or some bureaucrat is saying, 'No, you can't have this intervention that your doctor is proposing,' " Tunis says.

This sounds a lot like rationing, he says. Tunis' solution is to pay for new procedures before comparative effectiveness studies are done, but only if the outcomes of each one are put into a database for long-term analysis.

As for Kallmes, he says he's going to continue to do injections for cracked vertebrae in the hopes of figuring how both those who got the cement and those who didn't showed improvement.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))