Advocates for high-speed rail in the United States have lived a somewhat lonely existence over the past couple of decades. While there has long been talk about developing bullet trains in the U.S. -- similar to those in Japan, China and Europe -- there has never been much more than talk. Year after year, high-speed rail took a backseat in an autocentric and highflying culture.

"I would say it's been somewhat frustrating in that there just wasn't any support from the federal government," says Andy Kunz, president of the newly formed U.S. High Speed Rail Association -- a group created because under President Obama, high-speed rail is finally moving to the forefront of transportation planning.

In April, the president announced an $8 billion commitment in stimulus funding for high-speed rail.

"Imagine whisking through towns at speeds over 100 miles an hour, walking only a few steps to public transportation and ending up only blocks from your destination," Obama said.

The president gave a range of reasons why supporting high-speed rail is worthwhile: It can reduce travel times, highway and airport congestion, pollution and American dependence on foreign oil -- all while creating tens of thousands of jobs.

Kunz says hearing that from a U.S. president -- and then seeing the funding follow -- "was just amazing."

"That was certainly the most that's ever been put in one single shot for any rail system in America, no less high-speed rail," Kunz says.

Proposals From Across The Country

There is suddenly enormous interest in getting high-speed trains zipping from city to city in almost every part of the country. As the Obama administration prepares to begin doling out some of the first high-speed-rail grants from the $8 billion allotment, the Federal Railroad Administration has been swamped with applications. Forty states and the District of Columbia have already requested more than $100 billion for high-speed-rail projects.

Anybody that's ever traveled in France or Spain or Japan or China and has ridden on a 250-mile-an-hour train comes back to America scratching their head, saying, 'Why don't we have high-speed rail?'

"People want it," says U.S. Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood. The former Republican congressman from Illinois says he sees bipartisan support and hears very little criticism of the administration's plan to fund high-speed rail. "I think there's a tremendous consensus for it."

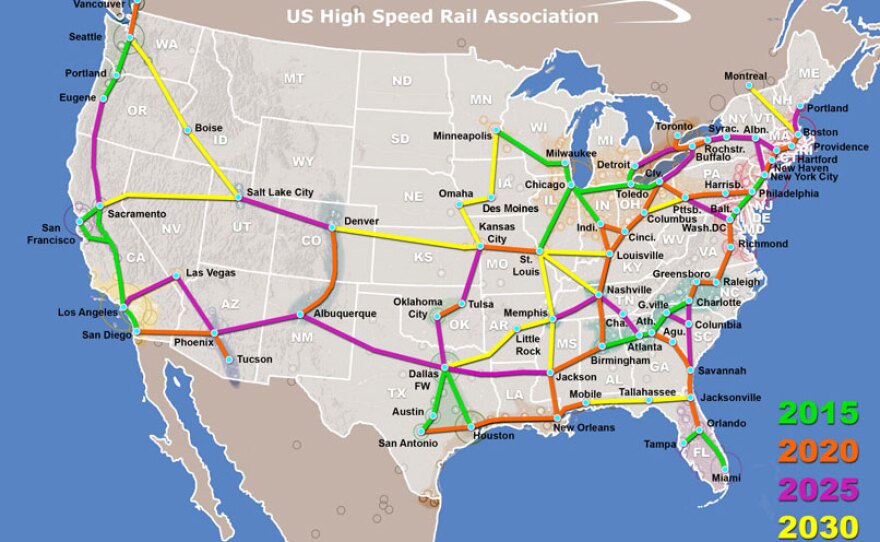

While any state can submit a proposal for funding, the administration has identified 10 potential high-speed-rail corridors: California, the Pacific Northwest, Texas, the Gulf Coast, Florida, a Southeast corridor, the Northeast Corridor, the "Keystone Corridor" through Pennsylvania, the "Empire Corridor" through New York, and a Midwest hub centered in Chicago. (See the High-Speed Rail map for detail.)

"Anybody that's ever traveled in France or Spain or Japan or China and has ridden on a 250-mile-an-hour train comes back to America scratching their head, saying, 'Why don't we have high-speed rail?' " LaHood says.

These Won't Be Bullet Trains

Passenger rail service has never been a transportation priority in Washington, especially since the 1950s, when President Eisenhower began building the interstate highway system.

"The signing of the highway bill promoted people getting into cars and driving all over the country. The reason other countries have high-speed rail is because their government promoted high-speed rail," LaHood says. "This is a new day in America and a new administration that is promoting high-speed rail."

However, this new emphasis doesn't mean that bullet-style trains like those in Europe and Asia will arrive in the United States anytime soon. Some high-speed-rail advocates question whether the administration is pushing for trains that will travel fast enough. They note that passenger trains operating in the United States as early as the 1930s routinely reached speeds of 120 mph and higher.

Today, only one Amtrak train model is capable of topping those speeds -- the Acela, which operates along the Northeast Corridor. The Acela can reach 150 mph, but only over a relatively short stretch of track. Acela trains average only 80 mph between Washington, D.C., New York and Boston.

LaHood acknowledges the definition of high-speed trains in this country will be more in the 130 mph to 150 mph range, compared with the much higher speeds in Asia and Europe, where the European Union has directed that new high-speed-rail lines accommodate trains traveling at least about 155 mph. Aging track, outdated signals and safety regulations restrict most other Amtrak trains from going faster than 79 mph.

Most of the projects now vying for the $8 billion in federal high-speed-rail funding are aiming for what some say are just "medium" speeds of 90 to 110 mph: the same speeds trains traveled at 70 years ago.

"In a way, we're going backwards, you know, if that's all we set our target for," says Kunz. His high-speed-rail organization is pushing for a nationwide system of trains able to travel 200 mph or more.

Only California is moving forward with that fast of a high-speed-rail system. An 800-mile-long high-speed-rail network with trains traveling up to 220 mph is being planned for the state. Planners envision passengers traveling from Los Angeles to San Francisco in a mere 2.5 hours.

Worth The Cost?

The estimated price tag for the California high-speed-rail project is $40 billion, and expanding this sort of high-speed rail network to the rest of the country would cost in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

"I do not think it's a wise investment in the U.S.," says Sam Staley of the libertarian Reason Foundation. Staley says the environmental, economic and other benefits of high-speed rail touted by supporters are overblown. He says too few people will ride the trains to make the staggering cost worthwhile.

"Forecasts for both cost and ridership are notoriously unreliable," Staley says.

High-speed-rail advocates dispute such criticisms and argue that there are plenty of people who would chose high-speed trains over driving or flying, especially to destinations 100 miles to 500 miles away.

Christine Jurowicz of Chicago is one of them.

"I would love to see train travel enjoy a renaissance," Jurowicz says, while seeing her adult daughter off on a flight at Chicago O'Hare International Airport. She says she would prefer to speed around the Midwest on a train, rather than fly or take other modes of transportation.

Her daughter, Hannah Jurowicz, who is on her way to Los Angeles and ultimately South Korea, where she studies and teaches, says she often rides high-speed trains there and that she would love to have that option in the U.S. over crowded airports.

"You have to get here so early, and I don't really like coming to the airport and checking in," Hannah Jurowicz says. "It would be great to do [high-speed] rail."

Missy Arendez of suburban Spring Grove, Ill., also thinks high-speed trains could be a viable option for some trips.

"It's all a trade-off between cost and time spent traveling," Arendez says. "But on a shorter trip, if it's feasible to get there in a couple of hours and you don't have to deal with the airport and it's significantly cheaper, it's a decent alternative, I think."

But Arendez points out that her flight to Kansas City takes only one hour, and a round-trip ticket cost just $120, so she says even bullet trains making that trip in three to four hours would have to be quite a bit cheaper to get her to choose riding the rails over this inexpensive and quick flight.

But transportation analysts warn that airline ticket prices are not likely to not stay this low for long. The price of filling up the tank in the family car is also expected to rise in coming years, with oil prices volatile and worldwide oil supplies dwindling.

See It To Believe It

Nonetheless, for high-speed rail to really gain a foothold in the travel marketplace, experts say it's important that the administration fund initial projects that can quickly become high-speed-rail showpieces, regardless of the speed.

"To make rail a major part of the equation is going to take years of proving to the public that this mode is here," says Joe Schwieterman, professor of public policy and director of DePaul University's Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development.

Schwieterman says an incremental approach -- such as upgrading existing Amtrak service to 110 mph on routes like Chicago-St. Louis and Chicago-Detroit -- if it's done well and soon, can help pave the way for other high-speed trains in the future.

"The public sees it works; they see the ridership; they see the trains; they see the advantages," Schwieterman says. "Then, that second phase of investment can begin."

He and others say it took five decades to build the interstate highway system into what it is today. Developing a true high-speed-rail network will very likely take decades, too.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))