As exhausted but jubilant Senate Democrats scramble home for the holidays, one more obstacle stands between them and final passage of the massive health care overhaul bill: the House of Representatives.

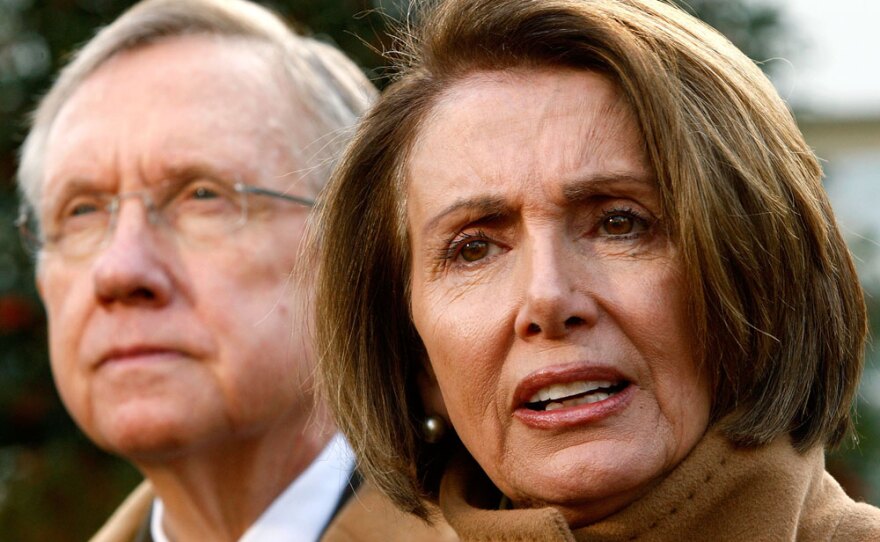

Democratic leaders from the House and Senate will spend the next few weeks trying to reconcile some key difference between their two versions of the health care bill.

The momentum toward final passage is gathering as the Senate approved its version of the bill early Christmas Eve. The measure would expand health care coverage to an estimated 30 million uninsured Americans and offer subsidies to help individuals and small businesses afford the new coverage.

But there is little room for negotiators to maneuver, with Democrats still divided over how to finance the expanded coverage, whether to create a government-run plan, and, in particular, how to restrict the use of federal funds for abortions.

"This is very precarious. Anybody who thinks this is done hasn't been around here very long," Democratic Sen. Chris Dodd said, discussing the negotiations. "There are large differences between the House and the Senate."

Both the House and Senate bills were the product of extended and intensive wrangling sessions, marked by painful last-minute compromises to win over moderate holdouts. Senate Democrats overcame a solid Republican filibuster with the absolute bare minimum of 60 votes. The House passed its bill in November by a five-vote margin.

Capitol Hill watchers agree that Democrats have invested far too much political capital in producing health care bills to allow the upcoming House-Senate conference to fail, but there are a number of land mines that negotiators will have to defuse.

"The Senate bill will be the main legislative vehicle, because it doesn't happen without preserving the 60 votes in the Senate," says Drew Altman, the president of the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. "But you can't ignore the House. There are powerful committee chairs who have worked this issue for most of their professional lives."

The Obama White House is also expected to be a major player in this process. Although Obama has largely refrained from endorsing specific proposals, many on Capitol Hill say that he will have to get involved to push a final deal through.

Thursday, Obama said he looked forward "to working with members of Congress in both chambers in coming weeks" on the reconciliation.

"We need to do what we were sent here to do: Improve the lives of the citizens we serve," he said shortly after the Senate passed the bill.

"This is the point where the White House puts its stamp on the details and engages on the details more than it has in the past," says Altman. "That doesn't mean necessarily that it does it publicly, but I do expect [it] to engage more on these detailed questions as it goes to conference."

Republicans, who have remained rock-solid in their opposition, will be largely on the sidelines during the talks. Only one House Republican voted for the bill, while the Senate version attracted no Republican support at all.

"We still have time to go down a different road, and rather than pursue a political kamikaze mission toward a historic mistake, I would hope that Congress would come to its senses in January and set a clear goal of reducing health care costs," said Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn.

House Democrats will very likely be forced to abandon the public option — the government-run health plan that would compete with private insurers.

But there are some key differences in how the bill is financed that will be harder to resolve. The House relies on a new tax surcharge on income over $500,000 for individuals and over $1 million for couples, while the Senate version raises money by taxing so-called Cadillac, or high-end, employer-sponsored health plans.

In an interview with NPR on Wednesday, Obama said that he expects the final version will meld elements of both bills, but that he does support taxing insurers that provide Cadillac plans.

"I'm on record as saying that taxing Cadillac plans that don't make people healthier but just take more money out of their pockets because they are paying more for insurance than they need to do, that's actually a good idea," he told NPR's Robert Siegel and Julie Rovner. "That helps to reduce the cost of health care over the long term."

Another looming gap is over affordability. The House bill offers more generous subsidies to help individuals without employer-sponsored plans and small businesses purchase health coverage in new insurance exchanges.

"I have thought for a long time that the focus on the hot-button issues, like the public option, has diverted attention from the meat and potatoes issues of actual coverage that people will get," Altman says.

Altman adds that a "sleeper issue" could be how the bills differ on the structure of the new insurance exchanges, where individuals and small businesses will be able to purchase coverage at what theoretically will be lower, competitive rates.

The House version creates a national exchange, while the Senate's exchanges are state-based. Insurance companies prefer the latter, but liberal Democrats believe a national exchange could give them a better platform to build on for additional reforms in the future.

This issue also plays into the divisive question of abortion, which could end up being the most difficult to resolve.

"It's a giant issue," says Altman. "It has the potential to derail everything."

The Senate brokered a compromise over abortion restrictions that allows individual states to ban federal funding of abortions in insurance plans purchased through their exchanges. Both bills preserve an existing ban of the use of federal funds for abortions.

But the House version includes stronger anti-abortion provisions inserted at the last minute at the behest of Rep. Bart Stupak, a conservative Democrat from Michigan. His measure bars coverage of abortion by any health plan bought even partly with federal subsidies.

Stupak has suggested the Senate version is not acceptable, while some Senate Democrats have ruled out provisions, like Stupak's, that are more restrictive than current law.

For now, Democrats are working hard to project a unified face, but there have been some signals from House members that they are not ready to sit back and accept the Senate version quietly.

Rep. John Conyers, the Michigan Democrat who chairs the House Energy and Commerce Committee, released a statement on Monday that originally said "material changes" would be needed in the Senate version, blasting in particular its "woefully insufficient" provisions for spurring competition in the insurance market.

"I am troubled that some senators believe that the House must accept the majority of the concessions embodied in this Senate bill," Conyers said in the first version of his statement.

But in a sign of how sensitive Democratic leaders are about the upcoming negotiation, the first version of Conyers' statement was replaced on his Web site by an edited version that significantly toned down his criticism of the Senate bill.

"I am committed to ensuring that the purpose of the health care conference is not to adopt and confirm the Senate legislation in its present form, but to combine and retain the better parts of both bills," the revised statement reads.

Some other House Democrats were much harsher, suggesting the Senate should scrap the bill completely and start over.

"A conference report is unlikely to sufficiently bridge the gap between these two very different bills," Rep. Louise Slaughter (D-N.Y.), wrote in an op-ed on CNN.com. "It's time that we draw the line on this weak bill and ask the Senate to go back to the drawing board. The American people deserve at least that."

The timing of the conference remains unclear as well. Democrats had wanted to produce a final bill before President Obama delivers his first formal State of the Union address. The date for that speech is not set yet, but the House is not back in session until Jan. 12. The Senate does not return until Jan. 19.

Obama administration officials are quietly hinting that Obama might not necessarily wait for a bill before delivering his speech, suggesting that the White House is worried the gaps could take a long time to bridge.

"You can't say there is no chance of it falling apart, but I would rank that chance as very slight at this point," says Altman. "At the end of the day, it's hard for liberals to walk away from a historic opportunity to dramatically expand health care coverage."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))