The Upper Big Branch mine in West Virginia was plagued by persistent problems with airflow in the weeks and months before a massive and deadly explosion in April, an NPR News investigation has found.

NPR has also learned that the FBI is focused both on the airflow problems and on possible tampering with safety monitors as part of its criminal probe.

The actual cause of the blast remains a mystery six weeks after 29 mineworkers died at the underground coal mine in Montcoal, W.Va. It was the nation's worst mining disaster in 40 years.

Dangerous gases have kept investigators out of the mine so far.

NPR contacted miners and supervisors who had worked in the Upper Big Branch mine. Ten agreed to speak with NPR on condition of anonymity because they said they would lose their jobs or would be unable to find work elsewhere in the coal mining industry if their names were disclosed. Most still work for Massey Energy, the company that owns the mine.

Ongoing Ventilation Problems

Most of the Upper Big Branch mine workers NPR interviewed point to continuing problems with the mine's ventilation system, which controls the airflow. Incoming fresh air dilutes explosive methane gas, which occurs naturally underground and seeps into mines. The airflow system also disperses coal dust, which acts like gunpowder and adds to the severity of an explosion.

The blast at Upper Big Branch stretched two miles. It was 10 times the magnitude of the explosion that killed 12 mineworkers in Sago, W.Va., four years ago.

Before the Upper Big Branch tragedy last month, many mining experts believed such massive explosions were a thing of the past. Federal investigators say the blast probably was fueled by a buildup of methane gas and coal dust.

The ventilation system and ventilation plans for all underground coal mines are critical to preventing explosions. But at Upper Big Branch, mineworkers told NPR, the plan was constantly changing in the months before the blast. And it never seemed to work.

"They wouldn't fix the ventilation problems," a former supervisor and a member of mine management said. "I told them I needed more air. They threatened to fire me if I didn't run enough coal."

Another miner said "there was constant confusion" in the management of the airflow system.

A third miner described mine managers this way: "They don't have a clue how to ventilate this place."

Massey Energy's Response

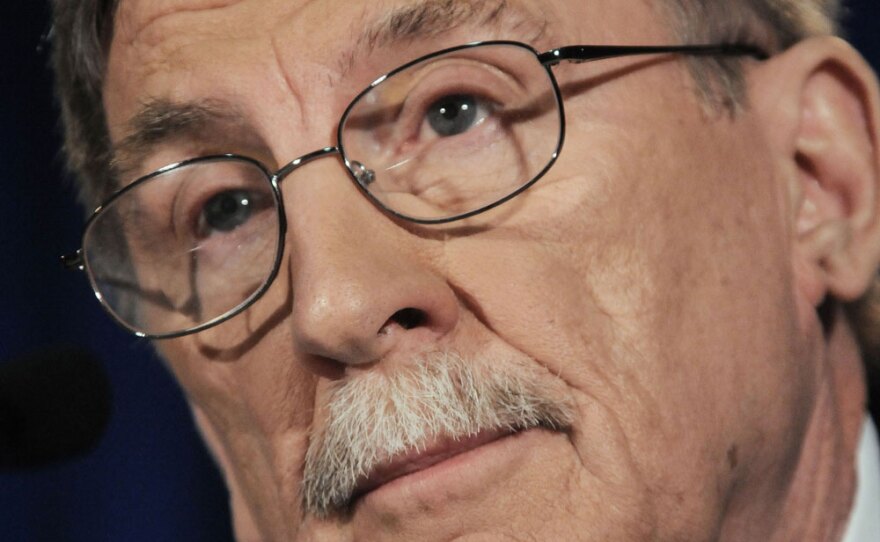

Those statements were read to Stanley Suboleski, the former chief operating officer of Massey Energy, who is now a member of the company's board of directors.

Suboleski insisted the mine always had sufficient fresh air and airflow. He is skeptical that mine managers would put production over safety.

"I would be just astounded that somebody would tell them to run coal without proper ventilation," Suboleski said.

But the Upper Big Branch miners and supervisors weren't the only people concerned about the mine's airflow system.

Federal Inspector Notes 'High Negligence'

Federal inspectors from the Mine Safety and Health Administration had been alarmed about airflow problems for months. In January, an inspector wrote a safety citation because air was flowing through part of the mine in the wrong direction.

Miners questioned management about the problem. The inspector wrote in his notes that the miners were told "not to worry about it." Had there been an accident, he added, men would have died from smoke inhalation.

In early March, an inspector found air going the wrong way again. He sent the workers out of the mine for their safety and told the company to fix the ventilation system.

The inspector labeled the incident "high negligence."

A Massey mine foreman told NPR that the plans for the airflow system became so mixed up, they would have been comic if the stakes weren't so high.

In one incident, mine managers gave a foreman a map with changes that needed to be made to the airflow system. The foreman and his workers followed the instructions and built cinder block walls called "stoppings" that channel air safely through the mine. On the next shift, the foreman said, management handed a completely different map to another crew, which promptly demolished the walls the first crew had just built.

"Management didn’t know what they were doing,” the foreman said, recalling the incident.

Massey's Suboleski suggests this was miscommunication, not mismanagement.

"[Mine employees] may not have understood why some of these things took place," Suboleski said. "I guess I'm surprised that they weren't given a better explanation of what happened."

Federal inspectors forced Massey to make changes to the airflow plan, Suboleski added, noting that these were changes the company opposed but complied with anyway.

Suboleski has a doctorate in mining engineering from Penn State, and he served as the chairman of the Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission during the George W. Bush administration. He has spoken for Massey on technical issues. And he says the changes mandated by the government actually decreased the flow of fresh air to a critical area of the mine before the blast.

"It was more complicated than it needed to be," Suboleski said. "In general, they made what ought to have been a fairly easy job more difficult. We had what I'd call a professional disagreement."

Investigating Airflow

A federal mine official says the Mine Safety and Health Administration made the changes in the ventilation plan because it was difficult to get enough air to all parts of the mine.

"You have to have enough air to ventilate each section," the official said. He requested anonymity because the agency's investigation is under way.

The FBI is also interested in the ventilation plans in its criminal probe, according to the questions FBI agents have asked some of the mine workers.

NPR first discovered the FBI investigation three weeks ago, when a reporter knocked on the door of the home of an Upper Big Branch miner. The man said he couldn't talk because he was in the middle of an interview with an FBI agent. NPR confirmed the federal criminal investigation with law enforcement sources familiar with the probe.

A reporter returned to the miner's home after the FBI interview. The miner said he was asked whether a Massey manager made unauthorized changes to the ventilation plan. He was also asked whether miners ever disabled methane monitors.

The monitors are required safety features in all underground coal mines. They detect the presence of methane gas and alert workers when the gas concentration begins to approach dangerous levels.

If the gas levels continue to rise, the monitors shut down mining machines. Monitors can be disabled by slipping plastic bags over the "sniffer," which measures methane. Or mine electricians can bypass the monitors using a wire.

Two of the miners NPR spoke with said they told the FBI they never saw anyone tamper with methane monitors at Upper Big Branch.

"It would take a whole crew of idiots to do that," one said emphatically.

Some of the miners NPR spoke with said they'd heard that this dangerous and illegal practice occurred in the mine, but none offered evidence.

Looking Into Tampering

Still, a federal official told NPR that investigators "will be looking very carefully to see if methane monitors were tampered with."

Massey's Suboleski said he would be shocked if an employee disabled a monitor.

"The company would never condone an action like that," Suboleski said. "We would immediately fire anyone if we heard of an action like that occurring. It's just not tolerated in the company."

Investigators also want to know whether the company kept accurate records of its methane readings. In fact, federal regulators told victims' families two weeks ago that they had discovered a methane record book with a page torn out and altered, according to two of the people present.

Suboleski acknowledged the extraordinary size of the Upper Big Branch explosion: "If you had asked me before this occurred, whether an accident of this magnitude was still possible in the U.S., I would have told you no," Suboleski said.

The role of ventilation in the blast -- if any -- and the questions about methane monitors won't be resolved before investigators can re-enter the mine. That could come as early as next week, according to a federal official. The investigative teams will inspect the methane monitors, look for ignition sources, work to pinpoint the cause of the disaster and try to figure out why it was so massive.

"I hope they find out what went wrong," one miner told NPR, as he talked about the 29 "buddies" he lost in the mine.

Then he quoted the safety signs he's seen every day of his long career underground. "Accidents are caused. They don't just happen."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))