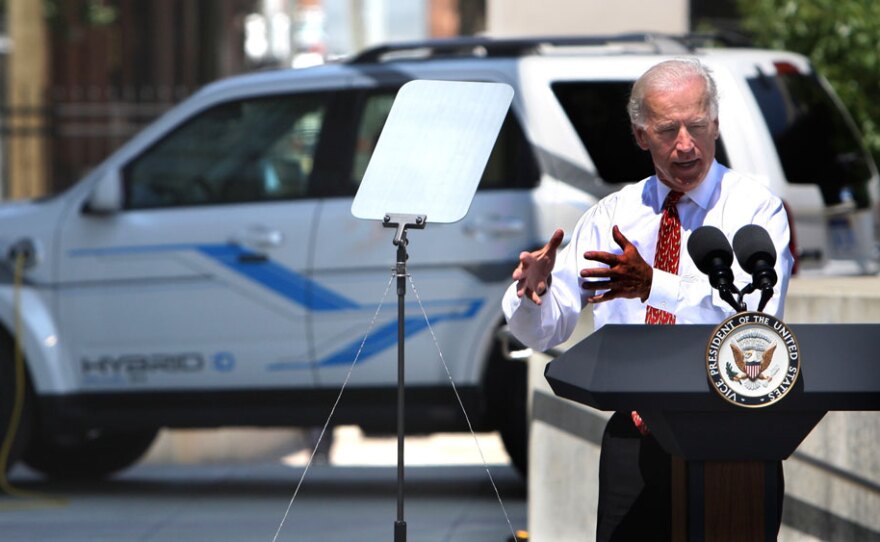

On Monday, Vice President Joe Biden will attend the groundbreaking ceremony of a new $600 million advanced battery production plant. For people who have been following the growth of this industry -- and tracking the billions of dollars the federal government has devoted to promoting it -- it comes as no surprise that Biden will be heading to Michigan.

Thanks to a combination of federal and state incentives for private companies, Michigan is suddenly emerging as a major center of production for advanced batteries -- the big ones that can power electric cars.

There are now 16 battery companies building factories in the state. Last month, Ford Motor Co. announced it would spend $135 million to retool a pair of plants to assemble battery packs and build electric drive transaxles.

Nearly half of Ford's investment is being underwritten by the federal government. All told, Michigan has attracted $6 billion in investment over the past 18 months geared toward battery-powered vehicle production.

Last year's federal stimulus package included 30 percent tax credits for clean-energy manufacturing facilities, as part of an effort not only to promote economic growth but to also address climate change. In August, Biden traveled to Michigan to announce that $1.3 billion in Energy Department grants for battery development and manufacturing -- more than half the funds available under the stimulus law during its two-year lifespan -- would be spent in the state. The plant in Midland he'll be visiting Monday received a federal grant worth $161 million.

"Frankly, these are the most significant subsidies I've seen in 17 years of doing this," says Randy Thelen, president of Lakeshore Advantage, an economic development firm in western Michigan. "I've never seen anything quite like this."

In his Tuesday evening Oval Office address about the Gulf of Mexico oil spill, President Obama underscored what he sees as the critical importance of such investments: "The tragedy unfolding on our coast is the most painful and powerful reminder yet that the time to embrace a clean energy future is now," Obama said. "Now is the moment for this generation to embark on a national mission to unleash America's innovation and seize control of our own destiny."

Hungry For Work

Michigan has emerged as a battery hub partly because of its historic strengths as a manufacturing center, but also because the state was aggressive about offering tax incentives that have supplemented the federal grant dollars for private companies.

Anticipating passage of the stimulus program in the early days of the Obama administration, the Michigan legislature in December 2008 approved a major tax incentive package to piggyback on it. The state has now spent some $2 billion on its battery efforts.

Michigan's main motivation, of course, is creating jobs. Other states may be struggling to emerge from the so-called Great Recession, but Michigan has never really recovered from the recession that officially ended in 2001.

The state has suffered the nation's worst unemployment rate for years. It's currently at 14 percent.

The Midland plant hosting Biden next week is expected to create 320 jobs over the next four years. Democratic Gov. Jennifer Granholm estimates that battery production should be good for 62,000 total new jobs in the state.

Even accounting for the inflated expectations such job projections are prone to, billions of dollars in fresh investment do offer new hope to communities that have long been struggling.

"There's no guarantee in life that this will be the next big thing," says Kurt Dykstra, the mayor of Holland, a city of 35,000 along Lake Michigan that has landed two of the big lithium ion battery cell plants. "But I'd rather be in the position we're in, having these two facilities in our community, rather than having them be somewhere else."

Secrets Of Holland's Success

Holland's two plants arrived courtesy of the same sort of help manufacturers elsewhere in the state are getting. The two plants have received between them just over $450 million worth of federal grants.

But why Holland? The city has long been a place that makes things -- one-third of its employment is still in manufacturing. That gives the two companies coming in to build batteries, Johnson Controls and LG Chem, the prospect of a base of local suppliers as well as a workforce with the right set of machine-operating skills to offer.

"The west Michigan area in particular has a long, decades-long heritage in manufacturing," says P.J. Thompson, president of Trans-Matic, a local precision metal work company. "We grow and nurture craftsmen here."

But Dan Clark, dean of Grand Rapids Community College's Lakeshore campus, notes that advanced battery work requires more skill in chemistry and electrical work than the kinds of manufacturing work Holland has specialized in -- making office furniture and interior parts for cars. To fill the gaps, both the community college and Grand Valley State University are offering new programs to train workers in areas such as energy engineering.

The state, the city, the local business community and the institutions of higher education have all worked cooperatively to make the area as attractive as possible to the battery makers. But Holland had one other big advantage over its competitors. The electric company is municipally owned and offers rates that are about 20 percent less than the Michigan average. That will more than offset the transportation costs involved in shipping batteries roughly 200 miles east to Detroit, or elsewhere.

Needing Jolts From Volts

A half-billion dollars worth of new investment is obviously good news for Holland, which has suffered through a "lost decade," as Mayor Dykstra says. But, he notes, "The ultimate success of these plants is going to depend on how many electric cars are sold."

Thompson, the Trans-Matic president, says he hopes to expand his workforce by about 10 percent to help supply Holland's new battery plants once they're up and running. But he concedes that some people in the area remain skeptical that even two large companies are enough to turn around the region's economic prospects.

"It remains to be seen how the lithium ion battery is commercialized in automotive," he says, "and what the public's true appetite will be for electric cars."

Few people believe that current lithium ion technology is adequate to replace gas-powered vehicles on a mass scale. As with other technologies, the advanced battery will evolve. But that means areas already fostering the industry should enjoy a leg up in the future, assuming they can adapt to future changes.

Nearly every state has some program in place to promote clean-energy technology and industry. Michigan's historic strengths as a manufacturing center -- as well as its willingness to invest heavily in this area -- will give it a big head start if and when clean energy really pays off.

The race is on worldwide.

"The Michigan programs not only get the companies in Michigan," says Rob Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington think tank, "but I would venture to say that in some cases, without the Michigan incentives, those plants would have gone offshore."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))