NASA has pulled the plug on one of its two Mars rovers. Spirit hasn't been heard from in more than a year, and now the space agency says it's abandoning hope that it will hear from the rover again.

Any disappointment that Spirit's mission has come to an end has to be tempered by the fantastic success of the robotic explorer. Intended to last 90 days, Spirit operated in Gusev Crater on Mars for more than six Earth years.

Indeed, just landing safely on Mars has to be considered a success, since the red planet has a way of devouring space missions.

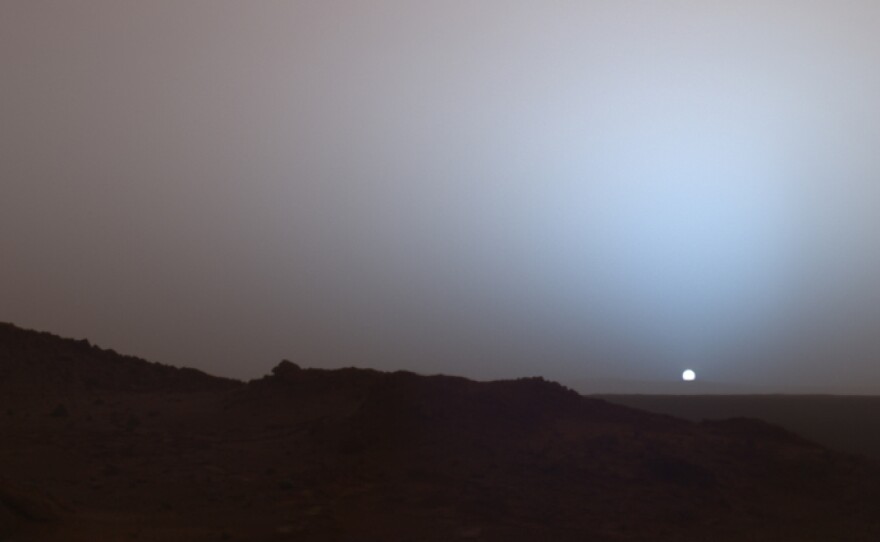

"When we landed, the view was spectacular, and everybody was very excited about the successful engineering achievement," says Jim Bell, now at Arizona State University. Bell was in charge of the main cameras on the rover. "What wasn't so clear is that there was a lot of scientific disappointment."

Disappointment because NASA sent Spirit to Mars to search for signs of water, and the rocks near the landing site were all made in a bone-dry environment.

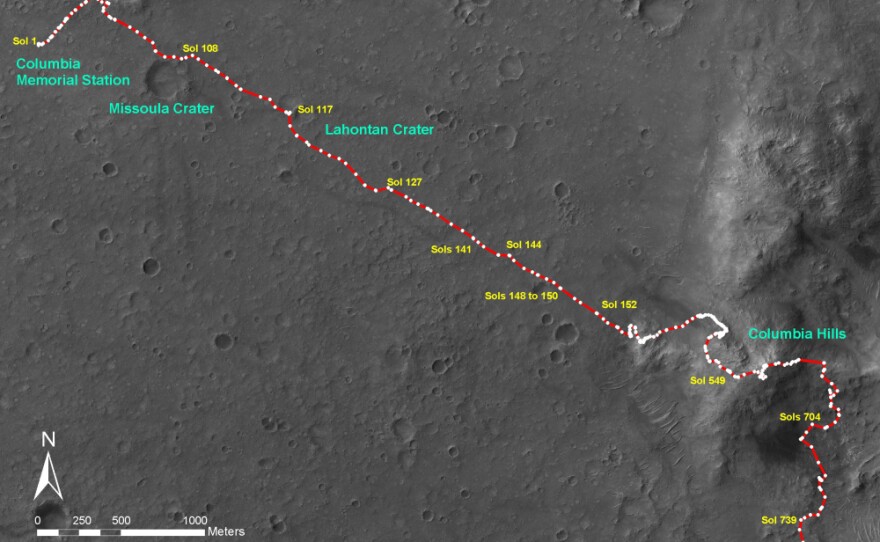

The rover landed on Mars in January 2004, near some interesting-looking hills. "We could see them 3 kilometers off in the distance, and it was kind of a wistful feeling. It was, Wow, look at that, there's some really cool geology up there, but man, it's 3 km away, we're never going to get there, no way the rover is going to survive to go that far," says Bell. "Of course, none of us thought we'd be sitting on top of that peak in the not too distant future."

Bell says up in the hills, the science really started getting rich. There were plenty of rocks that were probably made when lava bubbling from under the ground mixed with water percolating through the ground. "One gets a mental picture of a Yellowstone-like environment on this part of Mars 3 billion years ago or more. And by our reckoning, on this planet, that's a habitable environment," says Bell.

The next Mars rover mission, scheduled for launch in November, will be looking for other places on Mars that might be even more hospitable to life.

'They Are Very Much Like Living Creatures'

Scientists and engineers frequently become attached to their projects. But rover mission manager John Callas says the rovers engendered a deeper connection.

"They see, they move, they interact, they respond to our commands, and they think on their own," says Callas. "And so they are very much like living creatures, and so we've become very fond of them. I know I've become very fond of the rovers."

"We're used to waking up each day and seeing the latest from the rovers," says former project scientist Albert Haldemann. "And they're always there, day in and day out. And if one day that stops being the case, it's going to be very sad."

Now that day has come. In anticipation of a fourth winter on Mars, engineers put Spirit in a kind of deep hibernation mode in March of last year, hoping it would wake up with spring. But it hasn't.

John Grant is a planetary scientist with the Smithsonian Institution. He has worked on rovers since well before they landed in 2004.

"I've had two kids since then. The oldest is about to go into kindergarten. So really, the rovers feel like a piece of the family," says Grant, and it's hard to let go. "There was a sense that they've overcome so much in the past, that we'd here from her again." When that didn't happen, Grant says, there was "I guess a sense of denial, but also a very deep sense of loss that we're not going to hear from Spirit again."

Spirit may be gone, but there's still one rover left. Its twin, Opportunity, is still chugging along on the other side of Mars, although scientists know one day it will go silent, too.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))