Twenty years later, it's still the blue that haunts.

That cloudless day, the air just turning to autumn — the terrifying patch of bright blue sky that gradually appeared when the smoke parted just enough, revealing a space where the buildings had been.

Weeks later, I helped decorate the Cathedral of St. John the Divine for the memorial service of employees lost at the Windows on the World restaurant.

Blue hydrangeas, blue delphinium, green mountain laurel.

For me, 9/11 is inseparable from flowers. I was working in the high-end New York floral business to pay my rent while working on a novel, and this was a job that got you through the service entrance to the city's wealth—and all the way up an elevator to the 107th floor of Windows on the World in the North Tower.

I am among the lucky. I was off on that September morning; I did not lose someone close to me in the attack. Still, it took me two years and folding a thousand origami cranes before I could write an essay about that day; it's taken another 18 years for this piece to surface in print.

In that time, I've learned how grief accrues, a cruel accounting that comes with the blessing of each lap around the sun.

But I'm grateful for every day I've had since then, each one filled with its own joys and losses, both singular and quotidian. I moved four times and had four jobs. I got a mortgage. I got married and taught my stepsons how to make fried rice. My friend Fumie, who appears in the essay, moved back to Japan. My father died. My mother receded into dementia, but ever smiling. I found myself on the front lines of a global pandemic — a position seemingly as implausible for a writer as being at Windows on the World on the day before 9/11.

Blue hydrangeas, blue delphinium.

And now, look — that how brilliantly blue the sky continues to appear again, just like that September morning 20 years ago.

Here is the essay I wrote many years ago:

I love the city — this city. I came here 10 years ago from Ohio, purportedly to write. But really, it was the landscape I came for. I loved how Manhattan reached into the sky and how I felt a sense of space and joy amid all the noise and glass and concrete. I could walk outside and disappear, a glorious and intimate privacy for a girl who'd always stood out. I also loved how the city shouted at me and, in doing so, taught me to have faith in silence. I write mostly by ear now, picking my way through sentences as though trying to place a tune.

Yet the geography of my childhood haunted me, a persistent hum that finally broke through in the novel I did not want to write. Ten years ago, I drove out of rural Wayne County in an outrage — only to spend my days in New York rendering it with a tenderness that startled me.

So I wrote of Amish country and began to crave the feel of soil in my hands. Yet it wasn't the terrain of my girlhood I yearned for, but Oz, minus the flying monkeys. I'd already bailed out of newspapers and gone mad as a temp. I was tired of typing all the time, my wrist in bandages and my head in a mush. If I have to do something to make money, I thought, I want to work in flowers. I'd read an article about how people paying designers thousands to decorate Christmas trees.

"I can do that," I thought.

The Parsons School of Design cashed my checks and taught me how to decapitate roses and torturously rewire them so they looked natural. I discovered that florists cut everything with knives (I'm terrified of knives) and that designers get Lyme disease from handling bales of foliage trucked in from Jersey. I also learned those green blocks of floral foam were made of formaldehyde and manufactured in Kent, Ohio, my college town.

But on the first day I visited the wholesale flower market on East Twenty-Eighth Street at 7 a.m., I swooned. This was not Wayne County but a topography of dreams. I eagerly learned the names of everything and felt the power of Adam: lisianthus, hypernicum, delphinium, calendula. I loved these words, like names of goddesses. In contrast, my vocabulary as a journalist clanged and barked: lead, jump, nut, kill, cutline, double-truck.

In an amazing bit of luck, I got hired part time at a high-end studio in Chelsea, but it didn't take long to realize that though I loved flowers, I disliked most of the people who could afford to buy the nice ones. Someone who pays $250 a head for a fish dinner is often the sort who blows a gasket when encountering a leaf with a brown spot. Worse, I discovered that being an entry-level florist was an awful lot like being a temp, except it paid less and I bled more—thorns, knives, broken glass.

So all this is how I ended up on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center on September 10th, an enormous bunch of purple delphinium in my arms.

Flowers die. But it was our job to counter the natural order of things.

At the floral studio, we took turns going to Windows on the World every day to check on our flowers. In the main dining room were six arrangements, big as dog houses, and a modest one at the maitre d' stand. There were four other large arrangements scattered throughout the top floor, plus potted orchids for the bathrooms and topiary azaleas and fig trees by the elevators. The floral business is really about sleights of hand. Flowers die. But it was our job to counter the natural order of things, creeping in to freshen up things during the narrow opportunity between power breakfasts and the lunch buffet.

I was often annoyed. Patrons hid wads of gum, cigarette butts and candy wrappers in the potted plants. Women stole roses and snapped off stems of orchids in the bathrooms. The light was so bright in the dining room that the sun scorched all but the sturdiest flowers. We kept going back, frantically plucking out wilted stems and jamming in more spray roses.

"It's endless," my friend Fumie and I sighed. "Endless."

The thing I discovered about fancy restaurants, though, was that I loved watching the legions of people who worked, as it were, below stairs. I marveled at all that hidden machinery — the armies of Spanish men who ferried around crates of asparagus and buckets of ice, the West African women in housekeeping who sang folk songs in Senegalese while polishing acres of marble.

The ones who knew us by sight were very kind. The elevator girls cooed over the bundles of flowers Fumie and I carried, and the busboys held open doors. The waiters plied us with orange juice and sweet buns left over from the breakfast service and told us to steal rolls and butter and bottled Evian. The nice dishwasher, ever helpful, kept showering the potted azaleas with boiling hot water despite our frenetic waving.

But always, as we sprinted from room to room, pulling off dead leaves and shoving fresh Asiatic lilies into already overstuffed containers, everyone who worked below stairs kept asking in wonder, "What is this?" they pointed, "Is it real?" And we named each one: eremurus, hanging amaranthus, phalaenopsis, cymbidium. "Ah," they sighed. "We really enjoy these flowers."

The restaurant was streaming with smoke

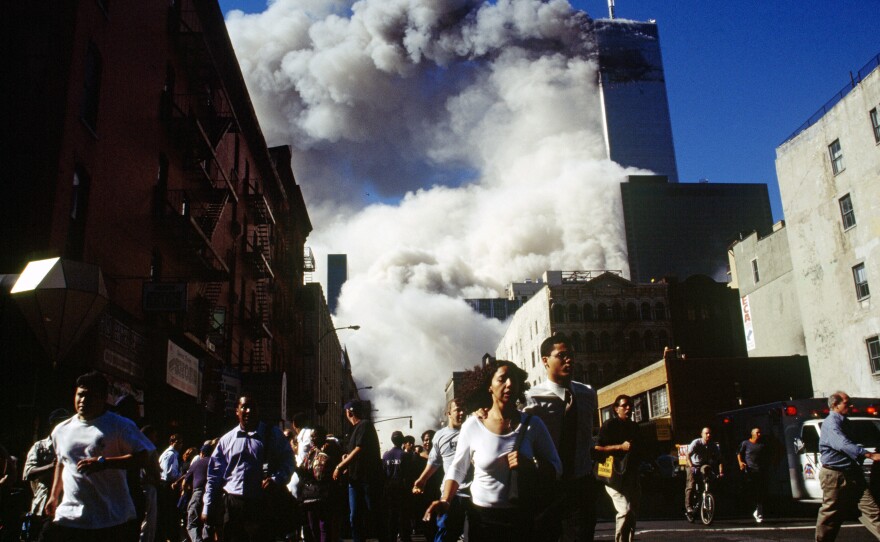

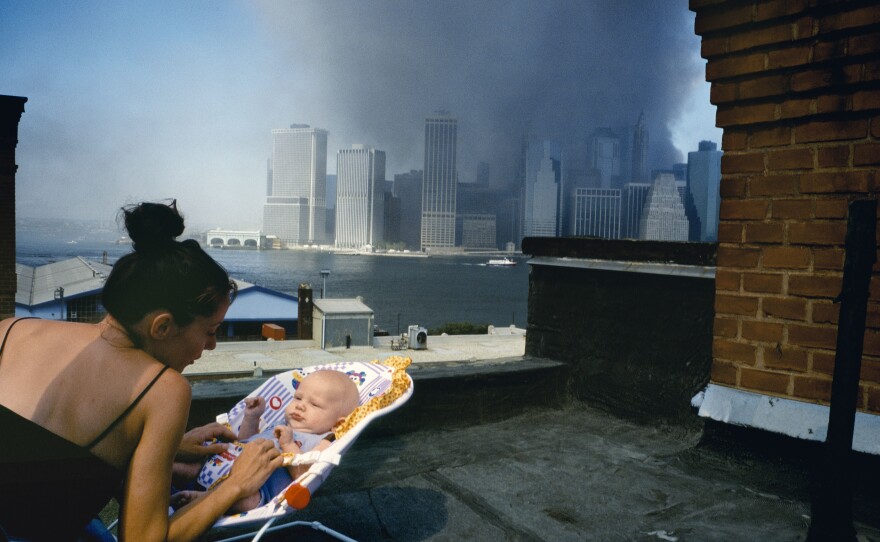

On September 11th, I looked out the windows of my Brooklyn apartment and saw the World Trade Center on fire, the restaurant streaming with smoke. I was still standing there in my pajamas when a grayish plane flew weirdly low behind the eastern pylon of the Williamsburg Bridge and slammed into the second tower, a wave of fire rolling outward. I walked in circles, finally managing to wash my face. When I came out from the bathroom, the entire tower had disappeared, a patch of blue sky showing through.

On a neighboring rooftop, a Hasidic man leaped into the air and flung out his arms, his whole body replicating the arc of collapse as he fell to his knees, screaming.

Fumie, I learned, had been on her way to Windows on the World but was detained at a Midtown restaurant, redoing the arrangements I'd made for the ladies room.

"They're all green," the manager complained. "Maguy won't like them."

We learned that 73 restaurant employees working on Tuesday morning were lost

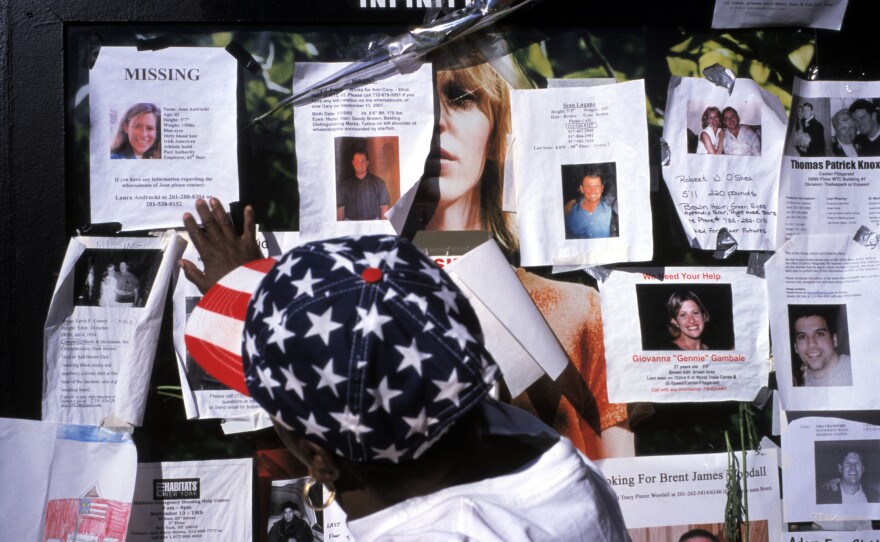

On Wednesday, the guys at the studio dismantled the 10 fresh arrangements that were to have been delivered at 4 that morning to Windows on the World. Off to the side, Fumie tied green hydrangeas and white lady's slippers into miniature silver cups for a wedding. We learned that 73 restaurant employees working on Tuesday morning were lost. The executive chef, Michael Lomonaco, survived because he was on the ground floor shopping concourse, getting fitted for a pair of glasses.

During the service, I opened the program and wept because I only knew the names of three people

Against all reason, the days continued one after another until, three weeks later, we decorated the Cathedral of St. John the Divine for the Windows on the World memorial service. The floral business is generally one that runs on emotional currency — happiness, desire, guilt. But our studio did parties, not funerals, and this was one we could not bear.

Branches of tiny pears. Delphinium and hydrangeas in blue and white. We made arrangements the size of sofas and lashed garlands of mountain laurel to the cast-iron candelabra.

During the service, I opened the program and wept because I only knew the names of three people. After the service, a manager came over and crushed me in her arms. Inexplicably, New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani shook my hand.

I swallowed every report compulsively, as though I could devour my grief

I do not remember when I stopped reading articles about 9/11. At first, I swallowed every report compulsively, as though I could devour my grief. But suddenly, I stopped. As an act of penance, I read the list of names each Sunday in The New York Times. I recognized the names of Doris Eng, a manager with neat gray pantsuits, and Jay Magazine, a salesman whom I repeatedly mistook for a periodical during my first weeks on the job.

Over the summer — in what must have been one of the most harrowing tasks in journalism — the Times reconstructed some of what transpired inside the towers before they collapsed. Reporters listened to hours of voicemail messages and cellphone conversations and interviewed the victims' loved ones. My co-worker at Brooklyn College could not stop herself from reading every word. She had nightmares for days.

"They had something about Windows on the World," Pat said quietly.

I made her tell me.

This is how I know that the rooms filled quickly with smoke after the first plane hit. It was very hot. There was no water. Some of the staff tore out the flowers from the green bamboo containers and bathed their hands and faces. Then they retreated into Doris' office and waited.

And then, on Tuesday, all of it vanished

The morning before, the sun had been glorious. It streamed in the tall, narrow windows of the restaurant and filled the rooms with light, bleaching out the purples and yellows in the flowers. Fumie and I carried trays, pulling the messy orange pollen cones from the lilies and plucking browned leaves from the quince branches. The quince fruits themselves were a delight, the color and shape of miniature golden apples, a charming rosy blush on the side. We examined our hands. The branches, while delicate, had slender, vicious thorns that broke the skin easily.

We watered the orchids in the bathrooms, and I called a friend from a pay phone on the 106th floor. Fumie looked out the window, waiting for me. There was one room on this floor that seemed like an architect's indulgence, good for a stolen kiss at midnight and little else. It was the size of a closet and hidden off one of the blue-toned conference rooms. The walls were covered in three-dimensional, faceted mirrors, as though you were standing inside a geode displaying crystals the size of cinder blocks.

Inside, there was a single conch shell of a chair — swirly, pink, plush and vaguely uncomfortable. After I finished my phone call, Fumie and I took a moment to rest before heading back to the studio. From that little room, we looked over Lower Manhattan, a Braille landscape of lesser buildings. At the tip of the island was the slim green curvature of the esplanade at Battery Park, built on all the dirt and rock that was excavated from the foundation of the World Trade Center. Beyond that was the glittering, gray-blue of the sea, the first embrace of a city that promised refuge for the world's weary and impoverished.

After a short respite, Fumie and I waved good-bye to the elevator girls and to the guard who kept watch over the surveillance monitors. We whooshed down the hundred-plus floors, the red numbers counting down our rush to Earth. We clicked through the subway turnstiles, our pockets stuffed with stray leaves and withered petals. We talked about what we should eat for lunch.

And then, on Tuesday, all of it vanished.

Andrea Louie currently works at the Nassau County Department of Health in Long Island, N.Y. She is the author of a novel, Moon Cakes, and co-editor of Topography of War: Asian American Essays.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))