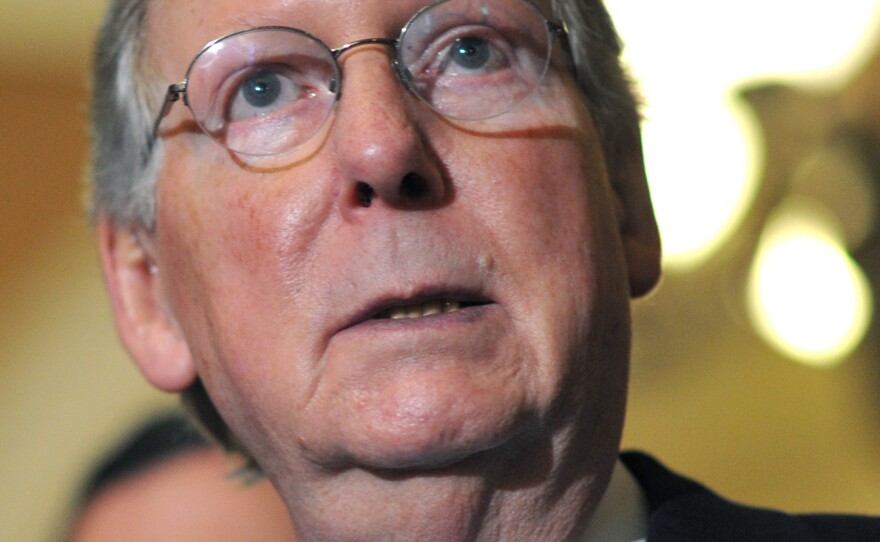

Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell is more than a little aggravated with the Senate Conservatives Fund, and who can blame him.

The youngish but well-financed Tea Party organization has targeted McConnell, a five-termer from Kentucky and highest-ranking Senate Republican, by helping to bankroll a primary challenger and using the race as an intraparty, us vs. them proxy.

McConnell in recent days has publicly accused the fund, which supported the government shutdown as an anti-Obamacare tactic, of "giving conservatism a bad name" and "participating in ruining the [Republican] brand." He reportedly scolded a Senate candidate from Nebraska in private for linking arms with the fund.

And last month McConnell's influence was apparent when the national committee that works to get Republicans elected to the Senate said it wouldn't do business with an advertising firm affiliated with the fund.

This is what former McConnell staffer Josh Holmes, now with the National Republican Senatorial Committee, told The Hill newspaper about that decision: "SCF has been wandering around the country destroying the Republican Party like a drunk who tears up every bar they walk into. The difference this cycle is that they strolled into Mitch McConnell's bar and he doesn't throw you out, he locks the door."

The fund's response went something like this: McConnell is a bully, full of threats and bluster.

Fighting words, indeed.

For those who don't slavishly follow party machinations and political money, we thought we'd take a quick look at the Senate Conservatives Fund, its money, and why it is causing McConnell and other establishment Republicans so much grief. The Kentucky conservative is just one of seven GOP Senate incumbents facing primary challenges of varying seriousness from the party's Tea Party wing.

Brainchild Of Tea Party 'Godfather'

The fund, a political action committee, was founded in 2008 by then-South Carolina Sen. Jim DeMint, a small-government conservative viewed by many as the godfather of the Tea Party movement.

When DeMint left the Senate earlier this year to become the president of the conservative Heritage Foundation, the fund, led by a cadre of his former staffers, including Matt Hoskins, got a national boost.

In taking the helm of Heritage, DeMint provided himself and the fund with an "institutional base," says Michael Bowen, "that most ex-senators who try to make policy don't have."

Bowen, author of Roots of Modern Conservatism, says that with the resources of Heritage, "DeMint will remain a force -- Heritage has a well-deserved reputation as a leader in the right-wing movement, and he's not going to go away."

That suggests that the DeMint-McConnell battle in which the conservatives fund is a key player will also continue beyond the coming election cycle -- assuming McConnell survives the primary against businessman Matt Bevin and can defeat the Democratic candidate, Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes.

Jonathan Strong, writing this week in the conservative National Review, traces what he characterizes as the DeMint-McConnell "feud" back to 2006, when they clashed over the issue of earmarks.

DeMint wanted a war on the congressional sweeteners, Strong says; McConnell did not.

Here's Strong:

"Their feud has been one of the most enduring -- and important -- clashes within the ranks of the Republican Party. Team McConnell thinks DeMint is a self-destructive showboat whose tactics, such as the government shutdown, can lead only to disaster. Team DeMint thinks McConnell is a petty, vindictive tyrant who pushes a mushy agenda behind the scenes. The battle raging in Kentucky is the culmination of seven years of on-and-off conflict."

The stakes in McConnell's Kentucky race, says Republican strategist John Feehery, can't be underestimated.

"This is a big fight," he says. "McConnell's got to make the case that this primary is a real waste of money, and that he's a real conservative.

"But [the SCF] has been able to tap into the anger of a lot of rank-and-file conservatives, and get them to give up their money," says Feehery, who characterizes the fund as a disruptive "nuisance."

Efforts to reach Hoskins, the fund's executive director, and Tom Jones, its political director, for comment were unsuccessful.

Big Money, Small Donors

The Senate Conservatives Fund raised and spent nearly $16 million in the 2012 election cycle. One of their top donors was the Koch Industries PAC, which gave $10,000, but has not contributed to SCF this cycle. The fund invested more than $385,000 in Texan Ted Cruz's successful run for the Senate and also helped Arizona's Jeff Flake vault from the House to the Senate.

But it also backed ideological candidates who proved unelectable statewide, including Todd Akin in Missouri and Richard Mourdock in Indiana. That blunted gains the GOP was banking on, repeating a scenario that played out two years earlier when the fund backed general election losers like Nevada Senate candidate Sharron Angle.

In 2012, the fund spent about $10 million against Republicans, including longtime Indiana Sen. Richard Lugar, who lost to Mourdock in a party primary.

The Center for Responsive Politics reports that the fund has already raised and spent more than $6 million on the coming 2014 cycle, including about $21,000 against McConnell. It has invested $105,895 in Bevin and this week sponsored an online effort to put together a $400,000 money bomb for the challenger.

The SCF says on its website that it "does not support incumbent Senators, but instead looks for new leaders who will stand up to the big spenders in both political parties." This year, it is extending its largesse to House candidates.

"They are one of the new standard-bearers for the Tea Party, and they represent the new 'take no prisoners' approach," says Sheila Krumholtz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, which at Open Secrets compiles information on money in politics.

The fund, she says, acts as an "earmarking" organization, collecting targeted individual contributions and passing them along to specific candidates.

"They are a major player in Washington and Congress," Krumholtz says. "Raising more than $15 million last cycle? That's serious money."

A comparable organization on the Democratic side, she said, is the left-leaning MoveOn.Org, which raised more than $19 million in the 2012 cycle.

A superPAC affiliated with the SCF, Senate Conservative Action, has also raised $1.3 million this election cycle. It has already made a $330,000 ad buy attacking McConnell for making a deal that ended the government shutdown; and it has invested $263,000 in ads for an insurgent Senate candidate in Mississippi where incumbent GOP Sen. Thad Cochran is up for re-election.

The pro-McConnell superPAC, Kentuckians for Strong Leadership, has invested $340,000 in an ad buy critical not of the incumbent senator's primary challenger but of Democrat Grimes. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is also running ads supporting McConnell.

Just to note: As of Sept. 30, McConnell's campaign committee had more than $9.7 million in cash on hand. Bevin, a Louisville businessman, reported in October that he had collected $222,000 in contributions and lent his campaign $600,000 of his own money.

Club for Growth Model

More than a decade ago, a largely unknown group of economic conservatives and tax-cut advocates called the Club for Growth was fomenting similar intraparty battles. It alarmed moderate Republicans with attacks on GOP Sens. Olympia Snowe of Maine and George Voinovich of Ohio and its backing of a primary challenge against veteran Republican Sen. Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania.

The Club for Growth collected $4.2 million in 2002. In the 2012 election cycle, it spent $4 million against Democrats and $10 million against Republicans. And, like the Senate Conservatives Fund, it invested heavily in Flake, Cruz and Mourdock.

But the Club for Growth, which gives McConnell an 84 percent "lifetime score" for votes he has taken on the group's key issues, has so far stayed on the sidelines in the Kentucky primary.

We asked the club's Barney Keller what the organization planned to do about the Kentucky primary, and when it planned to do it. "We're watching the race," he said.

Watching, we asked, as in "will continue to watch until it's over," or watching as in "we may jump in if we see fit"?

Keller: "Watching."

The club has lots of company.

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.