From San Diego to Siberia, researchers are joining forces to digitally recreate a very simple, very tiny worm. Their globe-spanning, volunteer-driven project is called OpenWorm, and it's raising big questions about our ability to simulate life.

When I met OpenWorm's San Diego-based coordinator, Stephen Larson, it was just barely 8 a.m. Already he was wide awake, Red Bull in hand, ready to start the group's biweekly meeting. The OpenWorm team sprawls over so many time zones, Larson doesn't have much flexibility in scheduling.

"For the guys from Novosibirsk, it's like midnight," he said.

Other contributors video conference in from Scotland, England and Los Angeles. They each have different skills and educational backgrounds, but they're all pitching in to build a digital simulation—with cell-by-cell accuracy—of the C. elegans worm.

If you're not a computational biologist, this probably sounds like a weird hobby. But it's actually a goal scientists have been trying to pull off for awhile now. Larson explained why:

"Something even as mundane-seeming as the way a worm wiggles and crawls is still a mystery in terms of what's happening, moment by moment, inside the nervous system. Which neurons are active? How are they influencing the muscles? Exactly when? Exactly why? When you take off the hood and zoom in and look at this world, it's actually very complex."

And all that complexity is squeezed into a tiny package. C. elegans worms are made up of less than 1,000 cells total, and they're about as long as a strand of human hair is thick.

"It has a very small sort of proto-brain, with 302 neurons," Larson said. For comparison's sake, human brains contain tens of billions.

Yet these worms show fairly advanced behavior. They mate, they seek food, they run from danger. And they're one of the most studied organisms in biology. That's why Larson thinks if our goal is to understand the brain as thoroughly as we understand a computer chip, taking apart this worm and putting it back together on a computer is an excellent place to start.

"What you can learn here from a crawling worm is applicable to humans," Larson said. "Because it has the same building blocks. The real goal is if we start understanding biology at that level, it lets us cure diseases in a way we've never been able to do before."

You could say OpenWorm is all about testing the limits of what biology actually knows about life, even at its simplest. Simulating life at any level is no easy task though. So far, OpenWorm has had some success modeling the worm's outer muscles of the worm. Larson plays me a Youtube video of their results.

A little pink and green worm undulates on his laptop screen in slow motion, kind of like a lava lamp. The video represents only a second or so of real-time worm movement, but the calculations involved took close to two days to compute.

Looking at this highly detailed model, I start to wonder... Could a computer-simulated worm be so accurate as to be indistinguishable from a real, living worm? If so, would that digital worm be alive in any sense of the word? I suddenly remember the bold claim from science fiction author Philip K. Dick, "We are living in a computer-programmed reality."

Is OpenWorm trying to reach the worm singularity? I pose such far-out questions to Larson, but he wisely avoids daydreaming too deeply.

"I fall short of suggesting something is alive or is not alive fully," Larson hedged. "Because I think that is a philosophical question. It's something that could be very controversial."

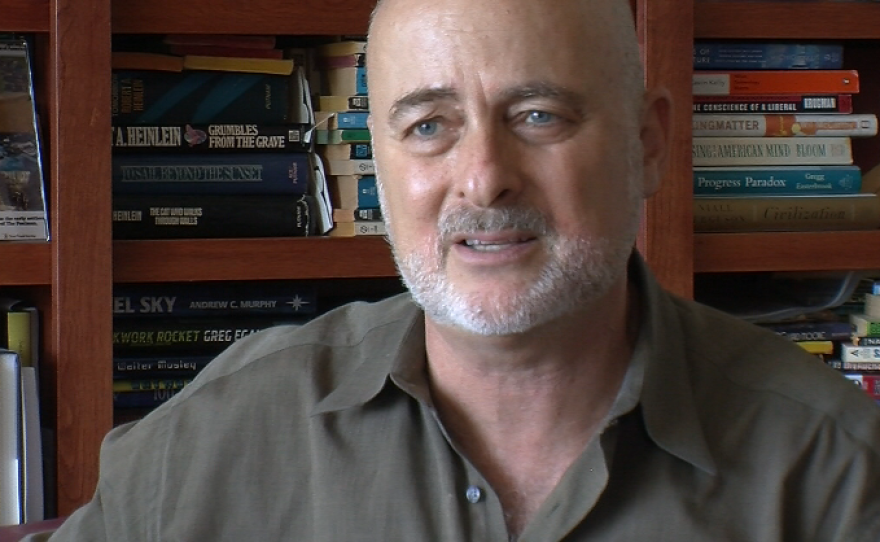

But these themes resonate strongly with San Diego-based science fiction author David Brin, who's taken a real interest in OpenWorm.

"There's always the question of how well the model matches reality, and whether or not there comes a point when the two merge. I've written science fiction in which humans have the ability to make copies of themselves. And these copies can move around and do as you wish. The C. elegans work is an example of science catching up with this ancient human dream."

Larson is the first to admit that OpenWorm is a long way off from realizing their goals. But he's also excited. Especially when he thinks about all the funding going toward brain modeling right now.

"There's a lot of exciting investments in this area, with the stuff going on in Europe, the stuff going on in the U.S. with Obama's BRAIN Initiative and all that. The next 10 years may be very exciting," he said.

Don't expect to see your digital twin soon, though. If programming a lowly worm is this hard, computer-simulating humans will be really hard. When talking about OpenWorm, Larson often likes to say we have to crawl before we can walk.