In their tenth debate with Donald Trump, Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz finally got real.

The two first-term senators, who have been chasing Trump in the polls and in February vote tallies, came at him on every issue their opposition research teams could muster.

They came at him for playing rough with immigrant Polish workers and for playing nice with Hillary Clinton. They called him out for supporting universal health care and for his neutral position on the Middle East. They ripped his businesses that went bankrupt and his for-profit school (Trump University) that went belly up.

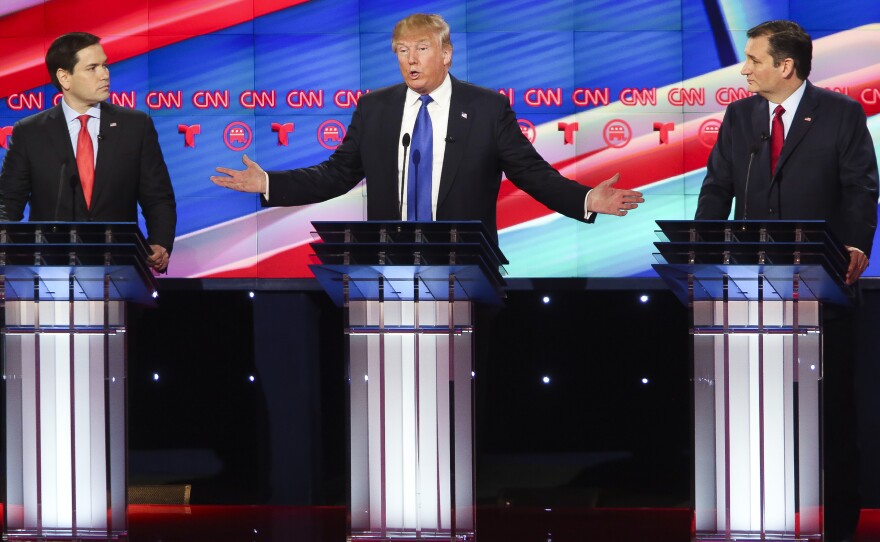

But at the center of the action in this debate carried by CNN and Telemundo was, once again, The Donald. He stood tall with the air of someone in command but under siege.

He swiveled to face Rubio on one side and Cruz on the other, steadfastly holding his own when the overtalk became a shouting match. Swinging his hands and arms in gestures to either side, he gave as good as he got in the rapid-fire marketplace of insults.

Ignore Rubio, he told the viewers, he's "a choker" who has "meltdowns" — a reference to Rubio's badly reviewed performance in the last New Hampshire debate on Feb. 6.

Cruz? "He's a liar" and "he works with nobody, and nobody likes him." Trump wrinkled his nose. "How many senators he works with have endorsed him? Not one."

It was not the first time Cruz had crossed swords with the front-runner. The mutual self-protection society the two pursued in the autumn faded as Cruz rose in the polls, both before and after he won the Iowa caucuses. Trump got tougher with him; Cruz responded in kind.

But on this night, Cruz was much more pointed in his ripostes, much more accusatory in his critique of Trump's views on health care and his delay in releasing his tax returns.

It was Rubio, though, who raised eyebrows and dropped jaws with his sudden reversal of tactics. After nine debates where he sparred with Cruz, along with Jeb Bush and Chris Christie, Rubio showed up with a new game plan. His relentless attacks were trained on Trump. He brought up the imported Polish workers who sued Trump, and the students who paid $36,000 for a year at Trump U and were left with nothing to show for it.

And if both Cruz and Rubio landed punches, it may have been Rubio who benefited more. Because in the most intense exchanges with Trump, Rubio was smiling, even chuckling and laughing. Cruz scarcely deviated from his dark visage, his stock sneer-scowl and his prosecutorial gestures.

It was a crossfire many Republicans opposed to Trump have waited to see, and not always patiently. It was the kind of concerted assault that, had it come earlier, might have kept some of the other candidates in the hunt for weeks or months to come.

But neither Cruz nor Rubio had seen it as well-advised to take on Trump in earlier debates, when they could see the damage done to others who challenged him and when they thought his presence in the field might be a boost to their own prospects.

Also on stage were Ohio Gov. John Kasich and former neurosurgeon Ben Carson. Kasich managed a minor share of the airtime, pushing his policy chops and his budget-cutting credentials and foreign policy credibility. Carson was left out through much of the broadcast's two-and-a-half hours, largely because the other candidates did not attack him or mention him — depriving him of a chance to respond.

"Can somebody attack me, please?" Carson said to the other candidates.

When he did get a foreign policy query of his own near the end of the evening, Carson quickly related his stands on a number of other questions that had been raised earlier of other candidates.

Gone were the foils who had complicated the wrestling match scorecard in the previous debates. There was no Christie to torment Rubio for his repetition of theme lines. There was no Bush to joust with Trump and be unhorsed as a consequence. (In a cruel irony of the evening, Barbara Bush and the first President Bush attended the debate, despite the fact their son Jeb had suspended his campaign five days earlier.)

And now there are just five more days before the results of Super Tuesday are known. This major haul of delegates based in states that seceded in 1861 or that identify with the Southern tradition was initiated in the 1980s by Democrats who thought their party's early primaries too tilted toward liberal candidates — or at least candidates who wound up losing in the general election.

About a dozen states will be holding primaries or caucuses, and Trump has at least a modest lead in the polls in all but one of them. That outlier state is Texas, where a strong second to Cruz would be nearly as good for Trump as a win. Trump seems poised to knock out Kasich in Michigan on March 8, or in Ohio on the 15th. He is leading Rubio in Florida by double digits in a poll by Quinnipiac University released the day of the last debate.

Unless someone stops or at least stalls Trump on March 1, he will have a lead in the delegate count and a momentum with GOP voters of the kind that leads to nominations. He will have won more, and faster, than any other non-incumbent candidate for the nation's highest office.

There have been calls for Kasich and Carson to drop out, but their votes might well distribute evenly across the three remaining camps. That would resolve nothing and clarify nothing.

Both parties continue to await their messiah. And in the interim, the desire for that wish to be fulfilled outstrips the patience of those who believe.

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.