Premieres Tuesday, March 28, 2023 at 9 p.m. on KPBS TV and the PBS App + Encore Wednesday, March 29 at 8 p.m. on KPBS 2

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE "The Movement and the “Madman” shows how two antiwar protests in the fall of 1969 — the largest the country had ever seen — pressured President Nixon to cancel what he called his “madman” plans for a massive escalation of the U.S. war in Vietnam, including a threat to use nuclear weapons. At the time, protestors had no idea how influential they could be and how many lives they may have saved. Told through remarkable archival footage and firsthand accounts from movement leaders, Nixon administration officials, historians, and others, the film explores how the leaders of the antiwar movement mobilized disparate groups from coast to coast to create two massive protests that changed history.

By 1968, the U.S. had been at war in Vietnam for four years and there were over 500,000 troops on the ground. 31,000 Americans had been killed, Nixon had defeated Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey, and the antiwar movement decided that something dramatic needed to be done.

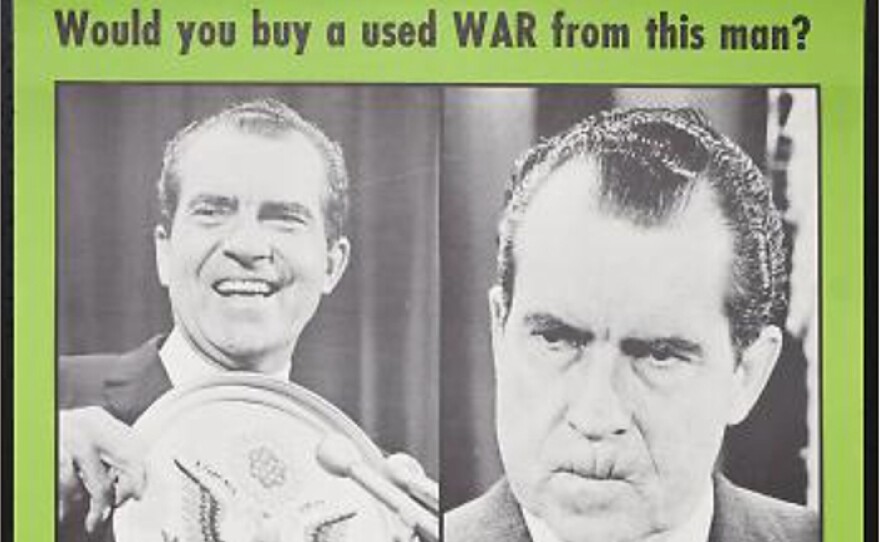

Although Nixon publicly belittled the movement, he was acutely aware that Lyndon Johnson’s presidency had essentially been brought down by the constant chants of protestors surrounding the White House. While on the campaign trail, Nixon vowed never to use nuclear weapons in Vietnam but, now in office, he came up with a plan to end the war: his “madman” strategy.

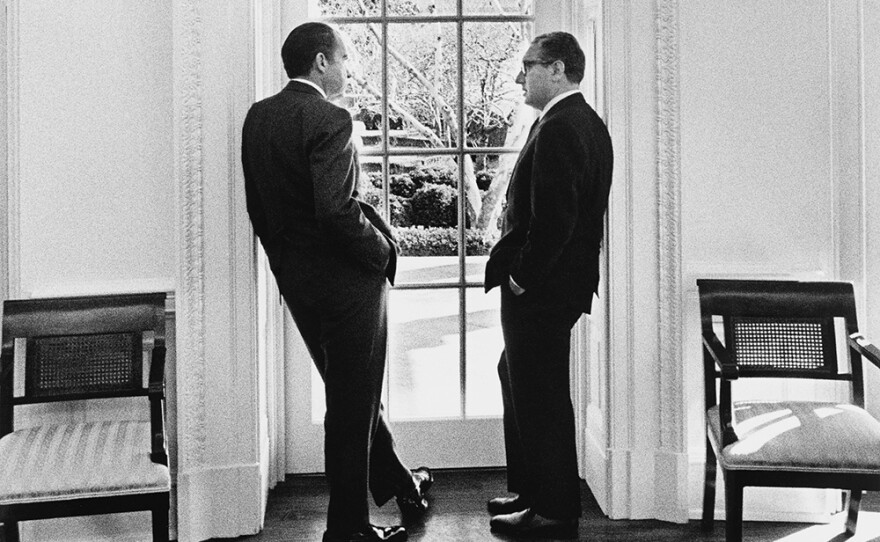

“His secret plan was to threaten the North Vietnamese with nuclear weapons,” said Morton Halperin, a Defense Department veteran and an aide to Henry Kissinger. “He was convinced that the way to make the threat credible was for the North Vietnamese to fear that he was crazy and might actually do this.”

In clandestine talks with the Soviet ambassador in Washington and the North Vietnamese in Paris, Nixon and Kissinger set a Nov. 1, 1969, deadline for Hanoi to accept U.S. terms for ending the war or face disastrous consequences. The National Security Council and the Pentagon began military preparations for bombing North Vietnam, mining Haiphong harbor, and using tactical nuclear bombs near the Chinese and Laotian borders. They codenamed the plan “Operation Duck Hook.”

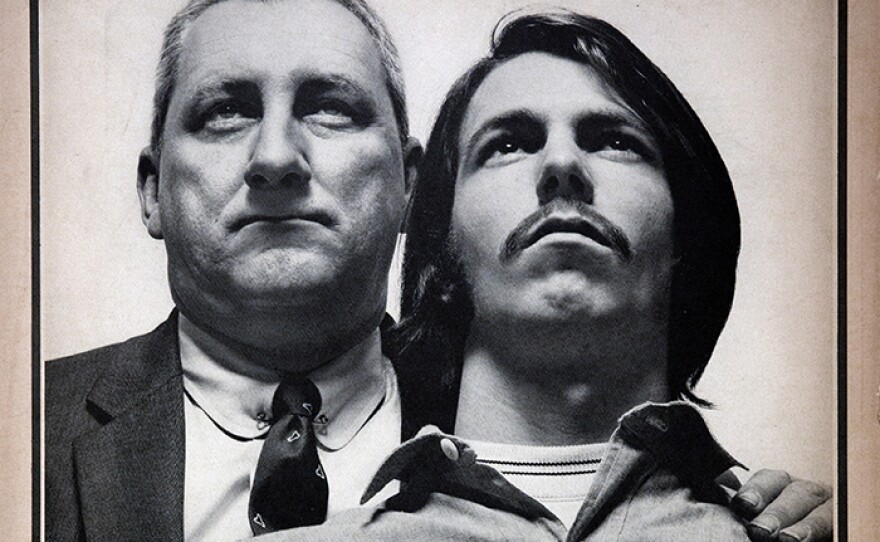

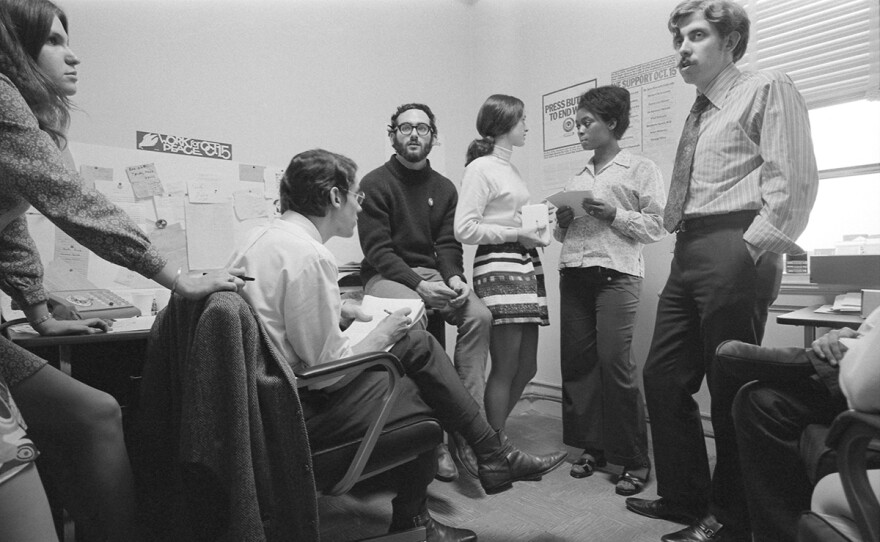

Unaware of the plan and with casualties continuing to mount, the leaders of the antiwar movement developed new and bigger ideas for protests in the fall. The first was to call for a Moratorium on October 15, 1969, a nationwide protest with an emphasis on local demonstrations throughout the country. The second plan, created by a sprawling coalition known as the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, was to organize what they hoped would be the largest peace marches and rallies the country had ever seen, scheduled for November 15, in Washington D.C. and San Francisco.

With an estimated two to three million people taking part on hundreds of campuses and over 200 cities and towns across the country, the October 15 Moratorium succeeded beyond the organizers’ wildest dreams. Dispelling the myth that the antiwar movement consisted solely of “hippies” and leftists, the Moratorium crowds consisted of labor leaders, church groups, civil rights activists, Democrat and Republican lawmakers, housewives, veterans, families and more.

“The word ‘protestor’ generally evokes an image of long hair and love beads,” reported ABC commentator Howard K. Smith. “But today, the crowds that marched and chanted and cheered the speeches looked more like a cross-section picked by the Census Bureau.”

Stunned by the success of the Moratorium — and facing the prospect of another massive protest on November 15 — Nixon decided to call off “Operation Duck Hook.” Years later, he wrote: “Although publicly I continued to ignore the raging antiwar controversy, I had to face the fact that it had probably destroyed the credibility of my ultimatum to Hanoi.”

But Nixon had one more move left and, later that month, he ordered a secret worldwide alert of U.S. nuclear forces to send what he called “a special reminder” to the Soviets and North Vietnamese of what he might unleash.

“Nixon assumed that he could bend Cold War adversaries to his will by making them fear that he was crazy enough to launch a nuclear attack,” said William Burr, co-author of "Nixon’s Nuclear Specter: The Secret Alert of 1969, Madman Diplomacy, and the Vietnam War."

Following the Moratorium’s success and with the November 15 demonstrations soon approaching, Nixon focused on discrediting the antiwar movement and the media for their positive coverage of the protests. In a nationally televised speech on November 3, Nixon blamed demonstrators for undermining the war effort and appealed to what he called “the great silent majority” for support.

Tensions built as the protests neared, with Nixon barricading the White House with buses and military troops. When November 15 arrived, as many as half a million protestors descended on Washington, while another 250,000 rallied in San Francisco. It was the largest single-day protest the country had ever experienced. Within earshot of the White House, the enormous crowd on the Washington Mall sang John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” as folk singer Pete Seeger shouted, “Are you listening, Nixon?”

He was. Nixon’s “madman” plan was shelved, and the nuclear alert ended.

“It was only decades later, when the archives were released, that we realized what, in fact, we had accomplished,” said Moratorium and Mobilization co-organizer David Hawk.

“We now know we had a big impact on Nixon and Kissinger, what they thought they could get away with in November, namely blowing Vietnam to bits, and maybe even using nuclear weapons,” said organizer Rev. Dick Fernandez. “They had to take it off the table. There were too many of us who were saying no.”

Watch On Your Schedule:

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE "The Movement and the “Madman” will stream simultaneously with broadcast on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.org and the PBS App, available on iOS, Android, Roku, Apple TV, Amazon Fire TV, Android TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO.

It will also be available for streaming with closed captioning in English and Spanish.

Credits:

Producer/ Director: Stephen Talbot. Editor: Stephanie Mechura. Executive Producer: ROBERT LEVERING. American Experience is a production of GBH Boston.