October is Filipino American History Month, and to celebrate, Chef Phillip Esteban talks about the cultural exchanges you can find in Filipino food. He will also be highlighting that food in an elegant dinner Thursday night at Artifact at the Mingei International Museum.

Earlier this month, I met Esteban of White Rice Bodega while covering the San Diego Filipino Film Festival (SDFFF). He has been a partner with SDFFF since its inception in 2021, so I knew his food was delicious. What I did not know was how well-versed he was in the cultural exchanges found in Filipino food and how that reflected the history of its trade partners and colonization.

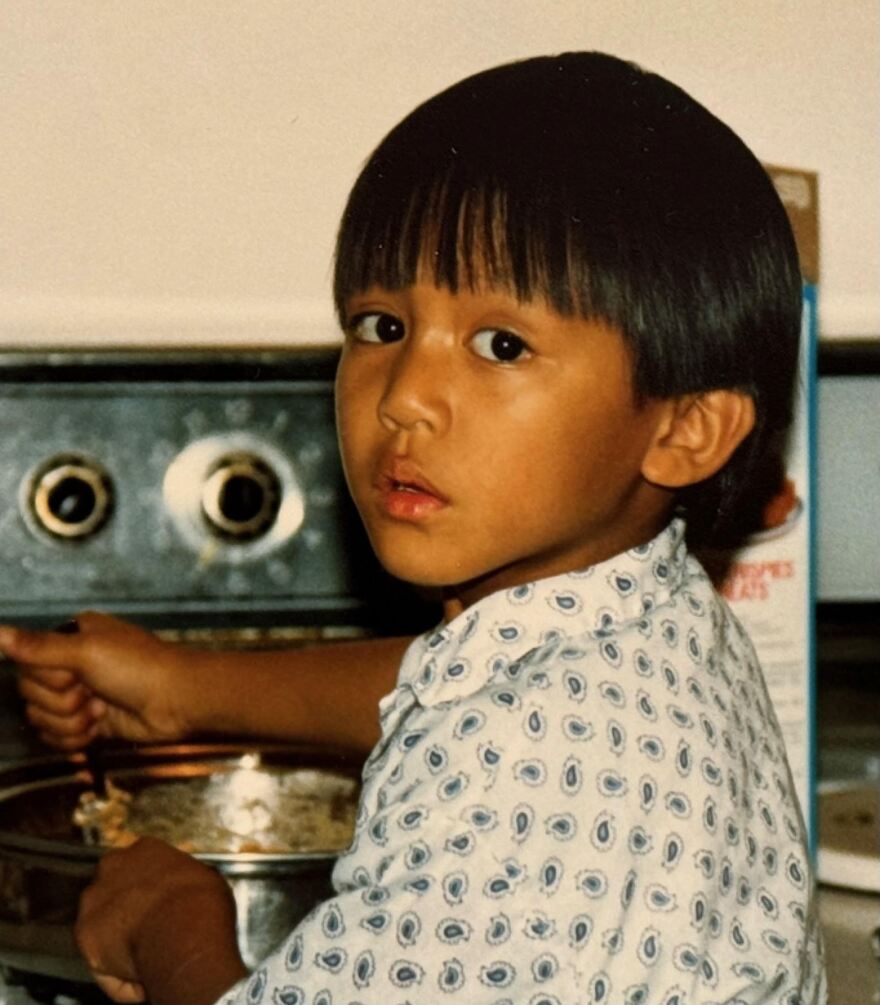

Chef Phil’s origin story

Esteban described himself as part of the “rebel generation” of Filipino Americans, “because we resisted the safe jobs. To our parents, it was just: you need to make good money, which means join the military, become a nurse or doctor, engineer. And there's nothing wrong with that. But you see a lot more Filipinos, especially this second generation and third generation, more in the creative spaces — art, culture, design, music, film.”

And food. Esteban’s earliest food memories go back to being a child and asking his grandmother to make his favorite desserts.

“So one day, I was like, six years old, and she asked, ‘Do you want me to teach you how to make it?’” Esteban recalled. “Probably so she didn’t have to do it anymore, and I just remember baking with my grandmother. And then in college, I remember still having the passion for food. I think Filipino culture, everything revolves around food, whether it's graduations or parties or birthdays. So in college, I was just hosting dinner parties, and my roommate was like, ‘Dude, you need to go to culinary school.' So I dropped out of college, and then enrolled to culinary school. My parents were definitely questioning what that path was, but they visited me at the first restaurant I was working at, and they could see how happy I was. They never said anything after that.”

But back in the early 2000s, Filipino cuisine was not on the menu at culinary school.

“The culinary world is a heavily white male-dominated industry,” Esteban said. “So all my instructors were Caucasian. All the chefs I looked up to were Caucasian. No one was really cooking Filipino food. And even when you talk about culinary school in itself and the way that they teach the program, each week, you cooked a different food from a different culture: China, Japan. But there was no Filipino food.”

But it was fellow Filipino chef Anthony Sinsay who told Esteban: “You need to cook our food.”

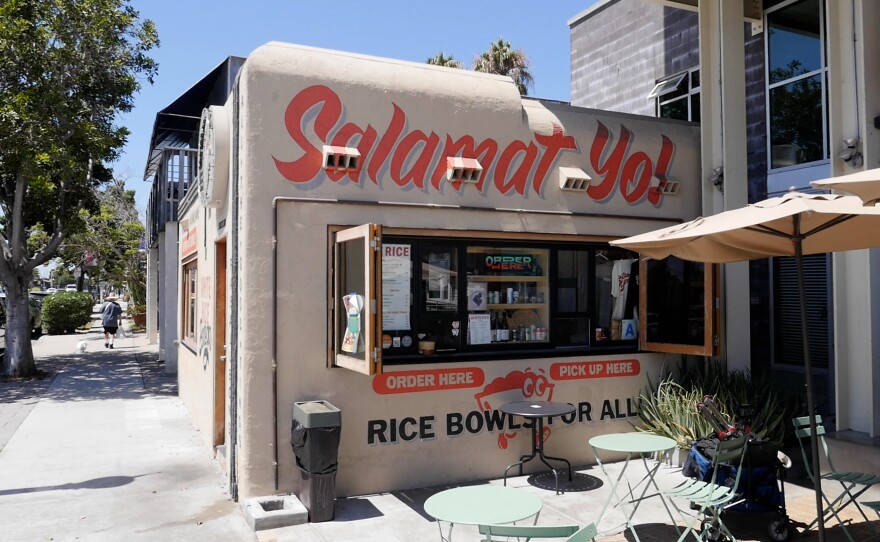

And that's when he came up with the idea for his restaurant White Rice.

“I wanted to make something lowbrow and approachable for a demographic outside of Filipinos,” Esteban explained. “There's taco shops everywhere, and I looked at tortillas as a vessel, and what is our vessel? White rice. Hence the name. I don't think we're doing Filipino food differently. I like to just say we're kind of repackaging it and making it presentable for everyone. So try and keep it classic, but just a little bit more vibrant for the eyes.”

Filipinos make up more than 40 percent of the Asian Americans in San Diego County, so that is a large community to tap into. Esteban opened his first White Rice at Liberty Public Market, which had special meaning since the area used to be the site of the Naval Training Center.

“When my dad was recruited in the Philippines by the United States Navy he came here to Liberty Station,” Esteban recalled. “Liberty Public Market was what we called the chow hall for the military. That's where he used to go eat when he first got here to America. And then I was born, and then in my teenage angst and youth, he said I should join. He put me in a military program to straighten me out. Our unit would march to that same galley, the chow hall, and eat there. And then full circle, fast forward to now, my first restaurant that I open is in that same food hall.”

Esteban now runs White Rice Bodega on Adams Avenue, Wildflour Delicatessen (coming to Liberty Station) and, earlier this month, his latest restaurant opened in Los Angeles located inside the Boulevard Market in Montebello.

Defining Filipino cuisine

Esteban described Filipino food as “one of the most complex cuisines because it's a balance between acidity (like vinegar), and sweet and sour, and salt because of soy, and having that many different complexities of flavor. Most cuisines only have maybe one or two things. I think that's what makes Filipino food unique.”

Along with other Filipino chefs, he's happy to have pushed to get large publications in San Diego to add a Filipino food category to their "Best of" lists.

“I'm very proud of what we did as a team, and that it allowed space for visibility — not just for us, but for our whole community,” Esteban said.

Cultural exchanges

Esteban noted that when his parents and grandparents moved to the U.S., they wanted all the children to speak only English. So he doesn't speak Tagalog, and that made him think about Filipino culture and how it is reflected in food.

“Which caused me to kind of go down this path of understanding our own food through our culture and history,” Esteban explained.

“The first era that we talked about ... was the Malaysian-Polynesian influence, which brought us rice, fermented fish, bagoóng. And if we didn't have that, a lot of the staple dishes like kare-kare, wouldn't be here. And then the next region was the Chinese traders, and that brought us pancit and lumpia. And then you think about Spain when they conquered the Philippines, and it was like, 250-plus years of influence on the food, which brought us empanadas, it brought us pork, it brought us bulalo. It brought us corn from Mexico, and it brought potatoes. If that trade didn't happen from Manila to Acapulco for the Magellan trade, there would be no sinigang," he said. "In culinary school, they talk about this idea of fusion cuisine, and I guess my instructors would say 'confusion is fusion cuisine' where, really, another country either colonized or influenced the food in some way. You think about Vietnamese food, and they have baguettes from the French, right? And they have sauté pans. And it's not like Vietnamese people are saying, 'Hey, I don't want that in our food.' There would be no bánh mì if they'd said that. But it's understanding history, and it's understanding our food.”

Then there is diversity even in classic dishes like adobo that can vary across the thousands of islands that make up the Philippines.

“There's 152 different ways to make chicken adobo,” Esteban said. “But everyone just knows the soy sauce, vinegar, black pepper and bay leaves (recipe). There's a very similar dish called tiyula itum, but in the southern islands of Mindanao, there's a big Muslim presence there, and because of it, there's this kind of curry flavor added to the cuisine that is so unique. They take the whole coconut, they cut it open and then they burn the entire thing, char it, char the skin, char the coconut flesh, and then they grate the inside out. And then while you're braising down the adobo pork, chicken, beef, they add in the charred coconut, add in different spices, they add some peppers, and it has this almost curry like flavor.”

Artifact dinner

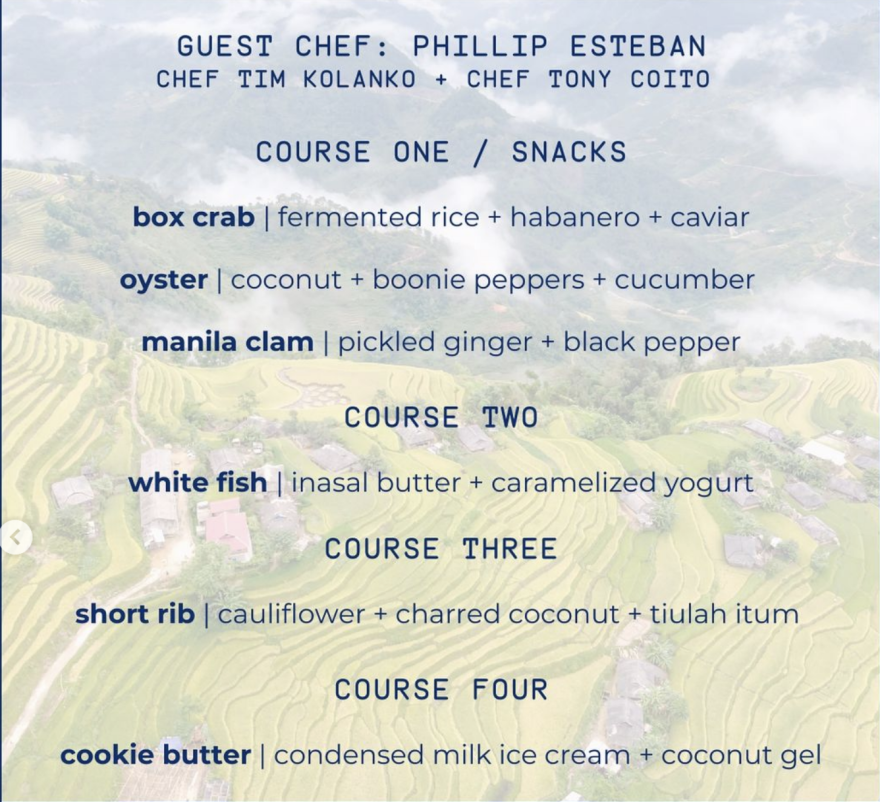

Tiyula itum will be one of the mouth-watering dishes Esteban is preparing for this month's regional prixe fix dinner at Artifact at Mingei.

“They have this amazing restaurant called Artifact and they do monthly themed regional cuisine,” Esteban explained. “Last month was Turkey, and this month — being Filipino American History Month — they wanted to do the Philippines. We have three snack items that we'll be serving including two variations of ceviche or kinilaw, an oyster and then Manila clams with a pickled ginger and red onion vinaigrette. And then the first course is local whitefish cured in a inasal butter with miso. The entree course is tiyula itum, so braised short rib with charred coconut and roasted cauliflower. And then the dessert course is, I'm making like a house polvoron, like a cookie butter almost with sweetened condensed milk ice cream. So condensed milk is something we put on everything in the Philippines. And I was like, let's make an ice cream base out of that, with a kind of polvoron cookie butter underneath. And then, like, little dollops of coconut gel and all the little herb garnishes to make it look pretty. It should be a fun, fun night.”

Fun and delicious! If you cannot attend the dinner at Artifact, you can sample Chef Phil’s food at any of his three White Rice locations.