Lt. Lazaro Chavez oversees a team that intercepts drugs smuggled from Mexico and the money heading back to the cartels. But Chavez isn’t anywhere near the border. He works 300 miles away, for the Las Vegas Metro Police Department.

“This is the battleground for us,” Chavez said. “Right here, Interstate 15.”

I-15 starts in San Diego, cuts through the Mojave desert, heads into Las Vegas, and onto Salt Lake City, where it turns due north.

The drugs that made it across the southern border are usually divided up in stash houses in cities like Phoenix and San Diego. They are probably heading to cities further north and in the Midwest.

Chavez and his team are also in charge of monitoring U.S. Highway 95 from Phoenix, the airport, trains and buses. But he says most of the action is on I-15.

“This is the road that the cartels have identified as their route,” Chavez said, standing next to the busy freeway. “And we have identified it as our area to really fight this battle.”

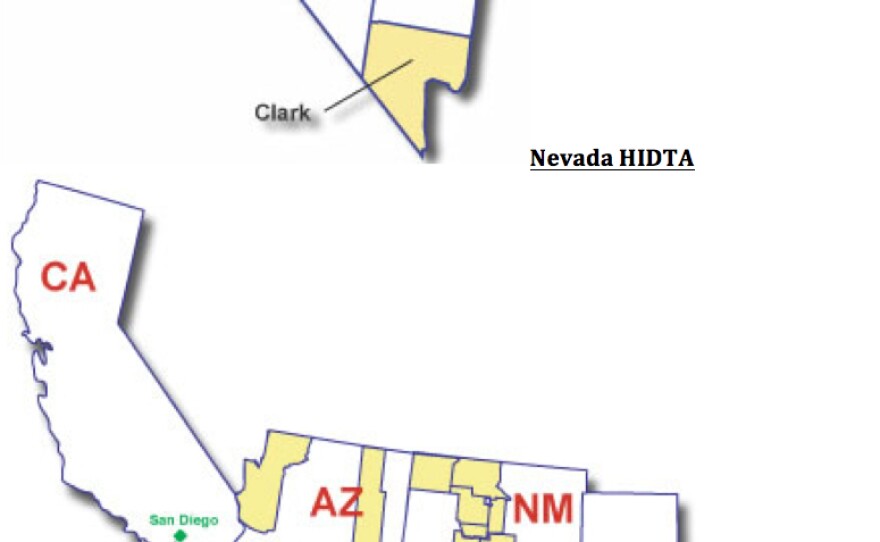

They fight this battle with some help from the federal government: $3 million annually for Nevada alone. Southern Nevada is one of 28 areas identified across the country as a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas, known as HIDTA for short.

Chavez and his team drive with police radios, but their cars are unmarked. That way, they can observe other drivers unnoticed.

“It is almost like a big chess game. The drug dealers want to outsmart the police so they can get their product...onto the streets,” Chavez said. “So we figure out, how are they doing it today? Are they using buses? Maybe they're using hidden compartments inside cars.”

“The last thing I want to do is give up some of our intelligence, some of our tools, so the bad guy wins,” he said.

The lieutenant has colleagues who do similar work all across the nation. About 400 officers who specialize in highway drug enforcement gathered in Las Vegas in early May.

They attended sessions with titles like: “Bulk Currency” and “Mexican Drug Cartels”. One priority that they talk about at these conferences is sharing intelligence between agencies.

And what would that message say?

“We just apprehended a driver who is cooperating. He told us there is another vehicle transporting drugs up ahead,” Killorin said. “It is a Cadillac Escalade, it has got Texas license plates and they are heading to Chicago, Illinois. And those troopers will respond to look for that vehicle.”

While collaboration may be improving, other aspects of the job may be getting tougher.

It’s becoming less common for those arrested drivers to cooperate and become informants, some authorities said. That may be a direct result of the Mexican cartels’ brutal enforcement strategies.

“They are not willing to talk because they are afraid of the cartels,” said Kent Bitsko, who directs Nevada’s HIDTA program. “They are a lot more afraid of what will happen to them if they cross the cartels than what will happen to them if they go to prison here.”

Those informants and sources of intelligence are critical to finding the cars with drugs.

“If you are not already being watched by law enforcement, the risk that you as the courier with the drugs will be pulled over is the (same) risk of anybody else being pulled over,” said Jonathan Caulkins, a Carnegie Mellon University professor who studies drug markets. “Which is to say, not very high. It really is needle in a haystack stuff.”

Back on the highway, Lt. Chavez shares his team’s stats from last year. They seized $2 million dollars in cash, more than 1,300 pounds of marijuana and about 100 pounds of methamphetamine, cocaine and heroin combined.

But that is a small fraction of the drugs a metropolitan area the size of Las Vegas is likely to consume in a year.

“You cannot help but to take it a little bit personal when you hear of search warrants being done in the city where you find 50 pounds or 100 pounds of methamphetamine,” Chavez said. “And you know that there is only one way it could have gotten here.”

And that is on the highway, probably I-15.