Building Islamic schools in Afghanistan has become a top priority for Afghan President Hamid Karzai's government as it struggles with the Taliban insurgency.

Officials hope the new schools will keep Afghan families from sending their sons to neighboring Pakistan, where many religious schools are said to be teaching boys to become militants. Karzai in July paraded one would-be teenage suicide bomber from a Pakistani school before reporters to prove that point.

But getting Afghans to accept the new government schools may take some work.

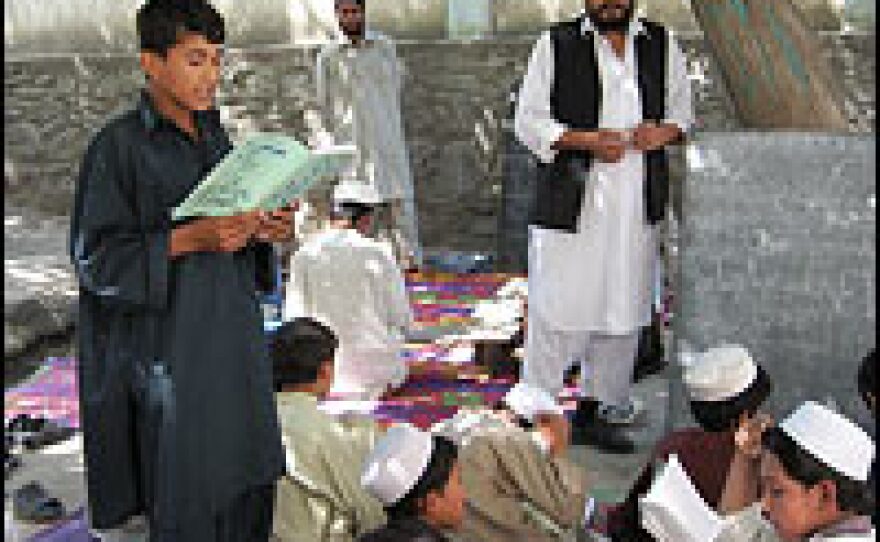

At a two-month-old school known as Dar Ulum, or House of Knowledge, in eastern Laghman province, young Afghans in prayer caps sit cross-legged on straw mats, rocking back and forth as they chant verses from the Koran.

Theirs is the only classroom in this 14-room religious school, or madrassa, that has anything resembling furniture. In this case, the furniture is small wooden trays to keep the Korans from touching the floor.

These young men also get to study indoors, unlike many of the 900 other male students relegated to straw mats beneath trees on school grounds.

But students at this school say they are happy. They say even an overcrowded, under-furnished compound along the busiest street in the provincial capital is better than having to go to Pakistan to study.

Jafar Mohammadi, 26, a student who returned from a Pakistani religious school to study here, says he also likes that the Dar Ulum teaches subjects besides Islam — subjects like science, math and even English.

But there are things he misses about his old school.

"In Pakistan, they provided us with accommodation, food and books," Mohammadi says. "Plus the school was in a quiet place. Here, we don't have these things."

School officials say they are trying to fix that. A top priority is getting funding for books, which for higher grades cost the equivalent of $200 per student. That's more than two months' income for most Afghans.

But with the Afghan Education Ministry determined to open Dar Ulums in each of the country's 34 provinces by March, matching the Pakistani model is not easy. The ministry also wants at least one lower-level religious school operating in each of Afghanistan's 364 districts. That, according to ministry estimates, translates into more than $70 million in building costs alone.

Why the rush? Both proponents and critics of the schools say it's because the Afghan government figured out that in this ultra-conservative tribal society, there is a high demand for Islamic education.

"This is something the government should have done six years ago," says former Taliban official and author Wahid Mujda. "But because of Western pressure, it went after things like women's rights. Women aren't terrorists, so their issues could have waited. So could building a democracy. Instead, the government should have cut off the roots of the problem."

The problem he's referring to is the growing insurgency, which many believe gets recruits from the many, pro-Taliban religious schools in Pakistan. A U.N. report in September found suicide bombers in Afghanistan often come from Pakistani madrassas.

But that's not how Afghan parents like Janatgol see it. He sends his teenage boys to a madrassa in Pakistan.

Janatgol, a driver from Logar province, says he became frustrated with regular Afghan schools because they taught his sons too little about the Koran. He says that during the Taliban's rule, the Koran was the only book he used to teach his children.

So a year ago, Janatgol sent his sons to a madrassa across the border. He says up to 10 other relatives are also attending schools in Pakistan.

Still, he says he would consider sending his boys to a Dar Ulum back home — but only if the mullahs teaching there are ones he likes.

That's a high hurdle for the Education Ministry, especially in provinces where the Taliban is strong. Deputy Minister Mohammad Siddiq Patman says officials are doing their best to hire qualified teachers locally. But the ministry also doesn't want anti-government rhetoric in the classroom.

"We don't check someone's ideology, but what we want them to do is teach the subjects, not the ideology," Patman says. "That's to everyone's benefit."

Taliban spokesman Qari Yousef Ahmadi says his group will be watching the schools closely. He says the Taliban wants to make sure the schools — some of which will be built with the help of Western money and reconstruction teams — do not become outlets for Western spies.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))